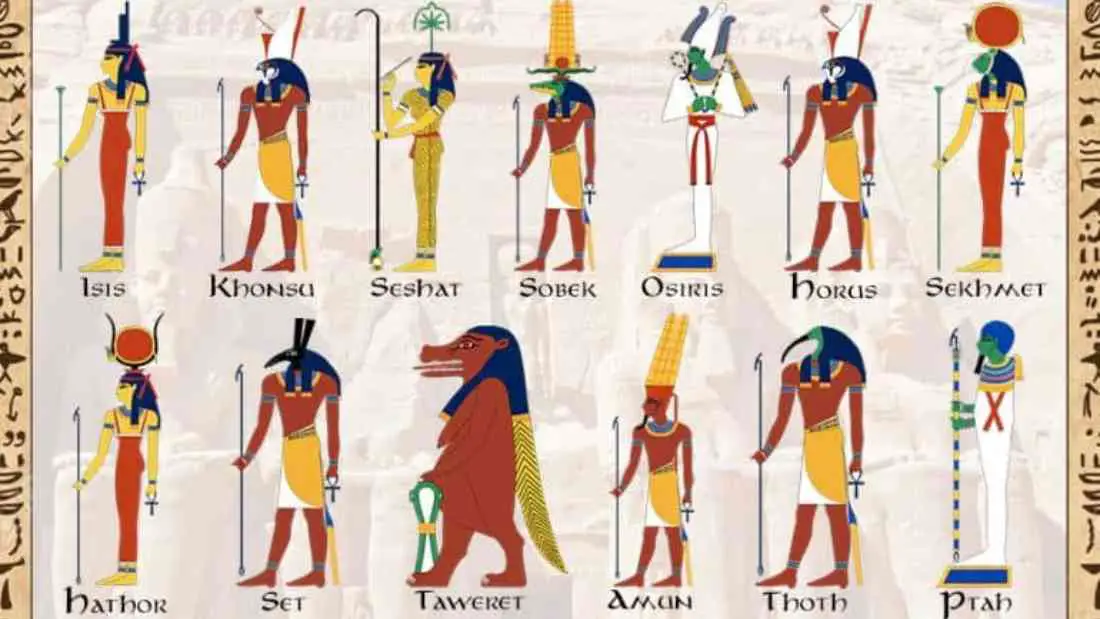

Ancient Egypt, a civilization spanning over three millennia, was known for its rich culture, which was deeply rooted in its religious beliefs. The pantheon of ancient Egyptian gods and goddesses, an assembly of more than 2,000 divine entities, was at the heart of this culture. Each god and goddess had unique attributes and realms, etching their significance into various aspects of life.

While names like Isis, Osiris, Horus, Amun, Ra, Hathor, Bastet, Thoth, Anubis, and Ptah echo through history and are widely recognized, numerous lesser-known deities were also integral to the intricate religious landscape, each holding significant roles.

The essence of ancient Egyptian culture was deeply intertwined with their belief and reverence for diverse array of gods and goddesses.

Each deity played a pivotal part in the perpetual journey of every individual’s life and afterlife. Their beliefs, rituals, and everyday practices were imbued with a profound reverence for these divine beings, underscoring the indelible influence of religion on their civilization.

Now, let’s delve deeper into the realm of the most revered gods and goddesses who held a sacred place in the heart of ancient Egyptian society.

Index – Ancient Egyptian Gods and Goddesses in Alphabetical Order

Aken – Custodian of the Boat in the Afterlife

Aker – The Guardian of the Afterlife

Amentet – The Welcoming Goddess of the Afterlife

Amun (Amun-Ra) – The God of the Sun and Air

Amunet – The Goddess of Hidden and Unseen Forces

Amunhotep, Son of Hapu – The Deified God of Healing and Wisdom

Anat – The Canaanite Goddess of Fertility, Sexuality, Love, and War

Anhur – The God of War and Hunting

Anti – The Hawk God of Upper Egypt and His Association with Anat

Anubis – God of Embalming and the Dead

Apep (Apophis) – The Celestial Serpent and Nemesis of Ra

Apis – The Divine Bull and Incarnation of Ptah

Arensnuphis – The Nubian Companion of Isis

Asclepius (Aesculapius) – The Greek God of Healing

Ash (As) – The Oasis Provider in the Libyan Desert

Astarte – Phoenician Goddess of Fertility and Sexuality

Atum – The Aged Incarnation of Ra and the God of Completion

Ba’al – The Storm God from Phoenicia

Babi – The Baboon God of Virility

Bastet – The Lioness Goddess of Ancient Egypt

Bennu – The Divine Bird of Creation

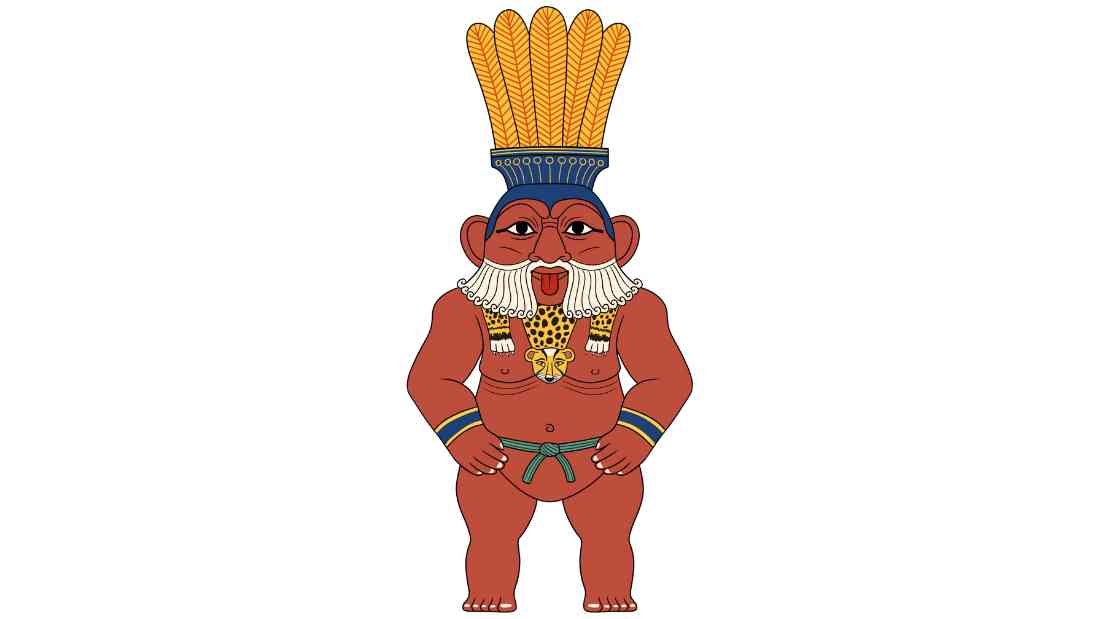

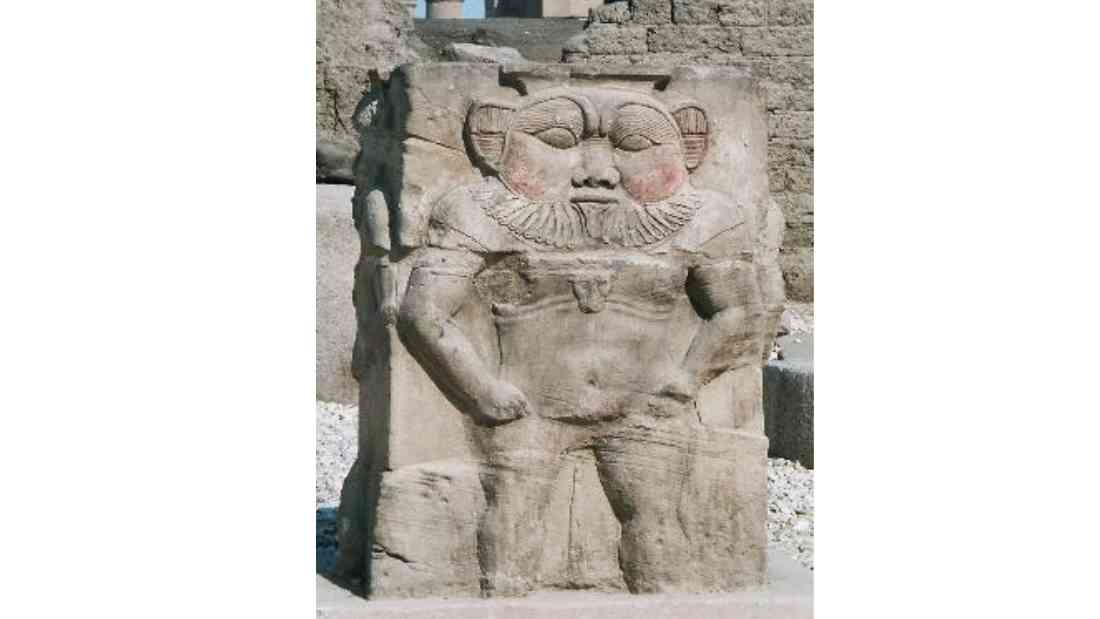

Bes – The Dwarf God of Childbirth, Fertility, and War

Beset – The Female Counterpart of Bes

Hardedef – The Deified Son of King Khufu and Author of ‘Instruction in Wisdom’

Hathor – Goddess of Love, Joy and Motherhood

Hauhet – The Goddess of Infinity

Hedetet – The Scorpion Goddess

Heka – The God of Magic and Medicine

Hraf-Hef – The Divine Ferryman

Ihy – The God of Music and Joy

Imhotep – The Polymath Vizier and Deified God of Wisdom and Medicine

Isis – Goddess of Magic and Healing

Kabechet – The Celestial Serpent and Funerary Deity

Keket – The Goddess of Darkness

Khepri – The Reborn Version of Ra and Scarab Beetle God of Creation and Rebirth

Khonsu – The Traveler and God of the Moon

Ma’at – The Goddess of Truth, Justice, and Harmony

Mehet-Weret – The Celestial Cow Goddess

Meskhenet – The Goddess of Childbirth

Naunet – The Goddess of the Primordial Waters

Nebethetepet – The Hand of Atum

Nefertum – The God of Perfume and Sweet Aromas

Nehebkau – The Protector of Souls

Nun – The God of the Primordial Waters

Osiris – God of the Underworld

Pakhet – The Lioness Hunting Goddess

Ptah – The Creative God of Ancient Egypt

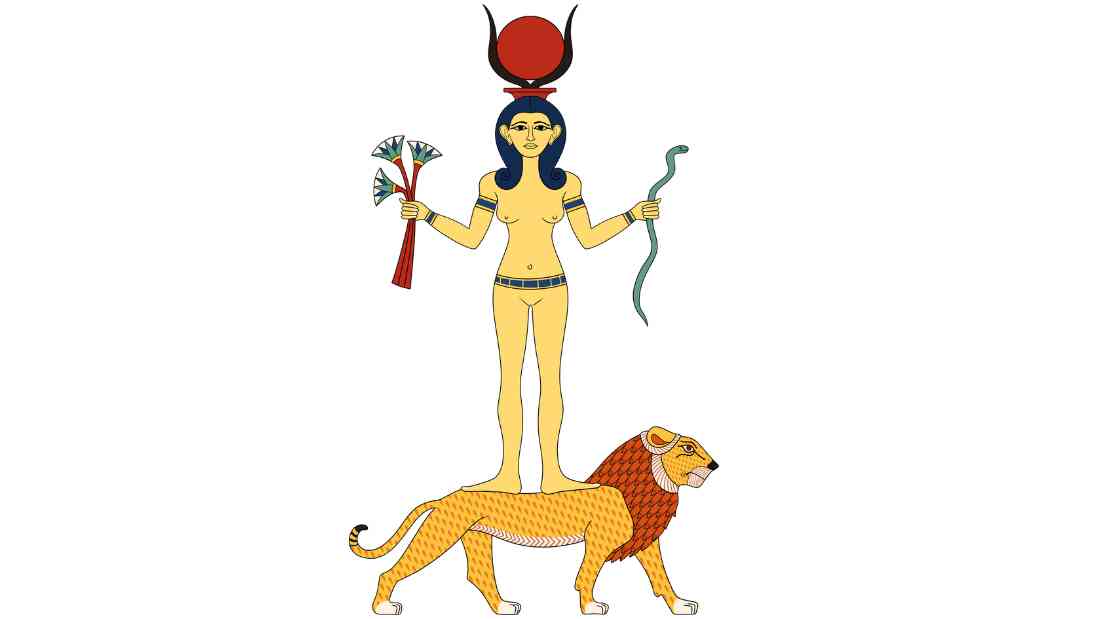

Qudshu – The Syrian Goddess of Love

Serket – The Protective and Funerary Goddess

Sobek – Guardian of Pharaohs and Protector of the Nile and Fertility

Thoth – The Enlightened God of Wisdom, Writing, and Knowledge

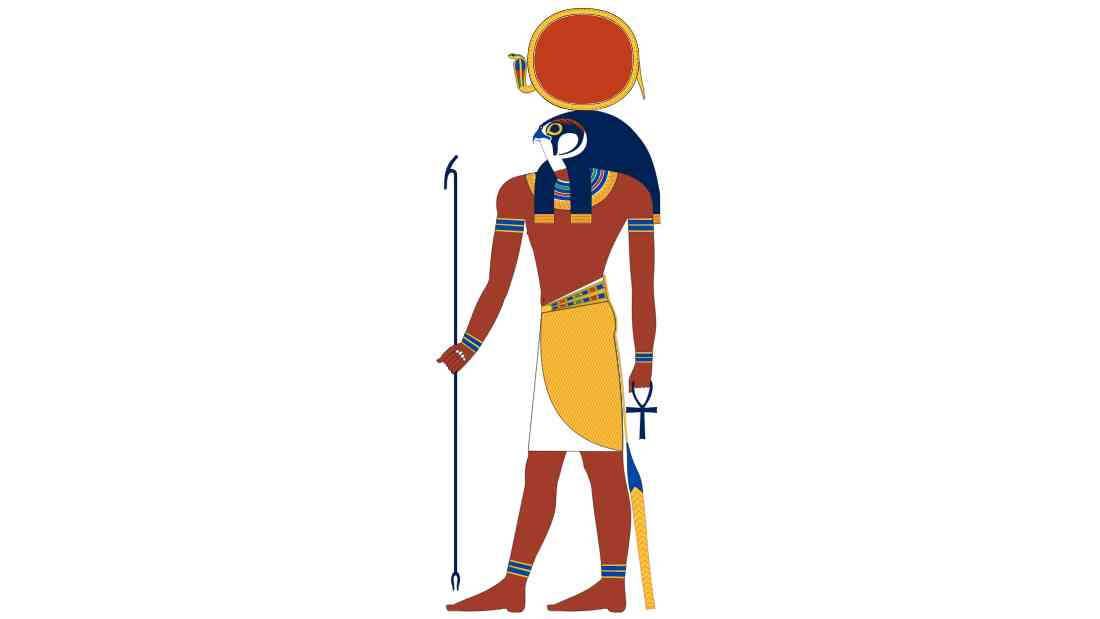

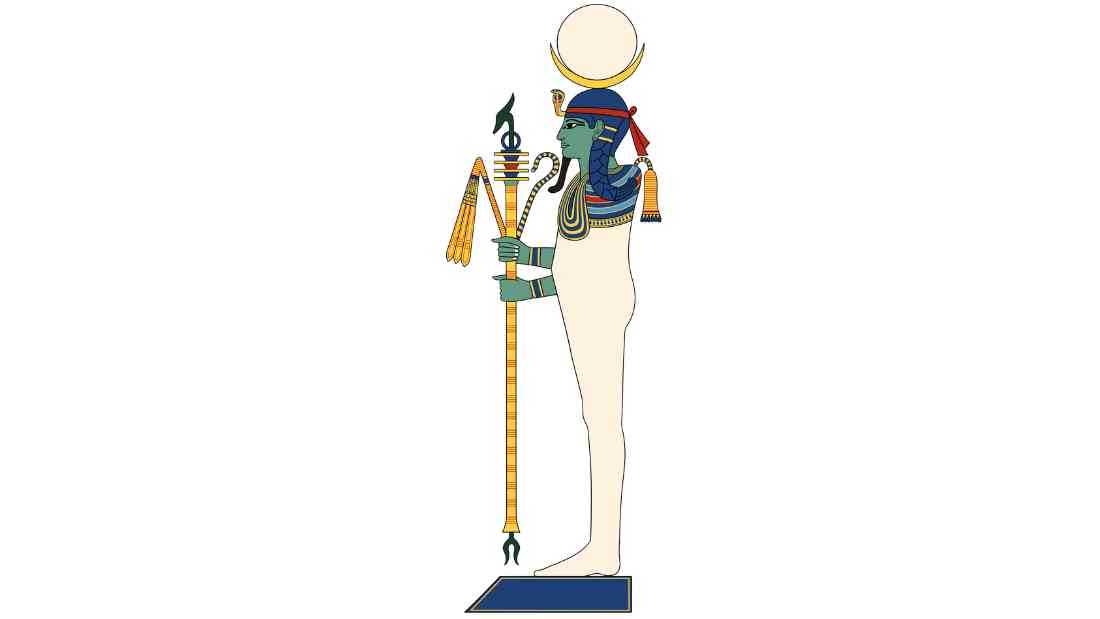

Ra – The Majestic Sun God

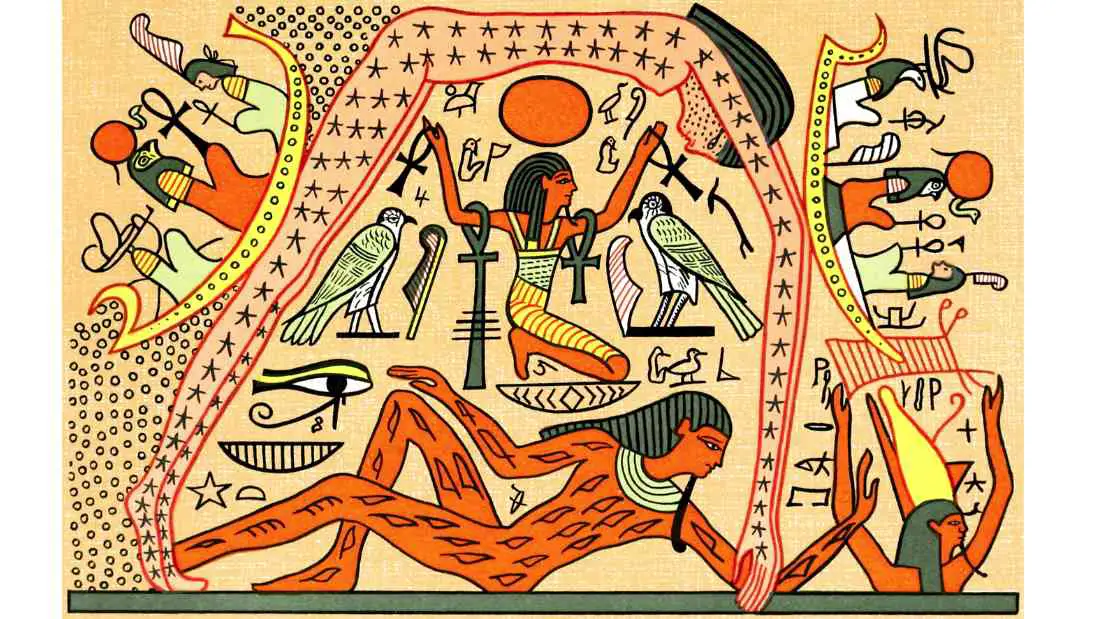

Ra, the resplendent deity who ruled the sky, sun, and universe, holds a position of unparalleled honor and reverence in the pantheon of ancient Egyptian gods.

As a god of immeasurable influence and power, he was intrinsically linked with the sun, creation, and the divine right of kingship.

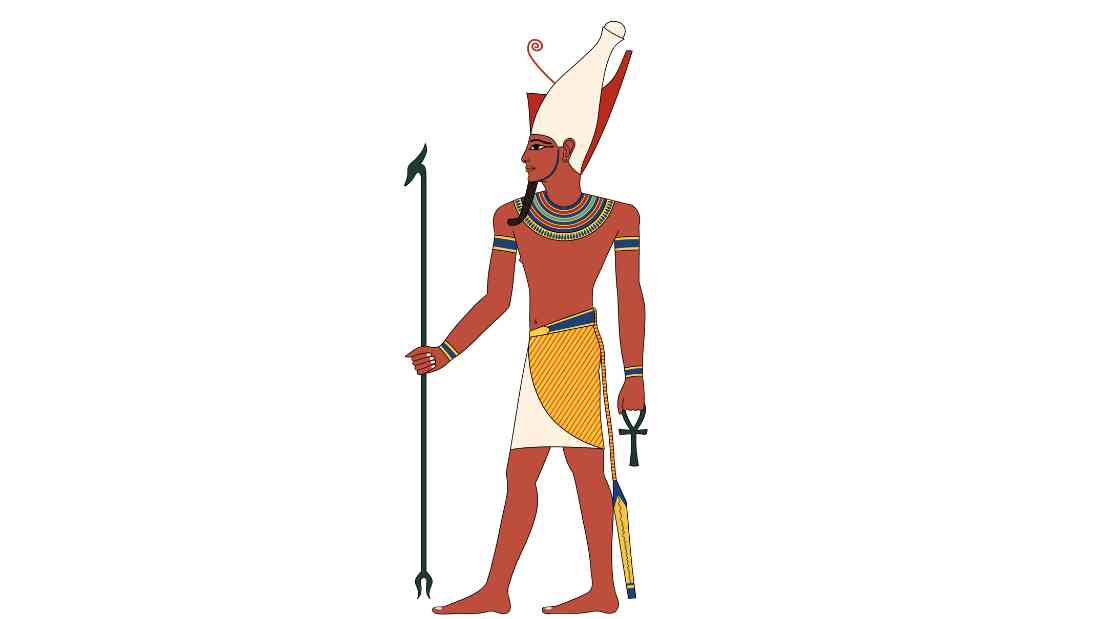

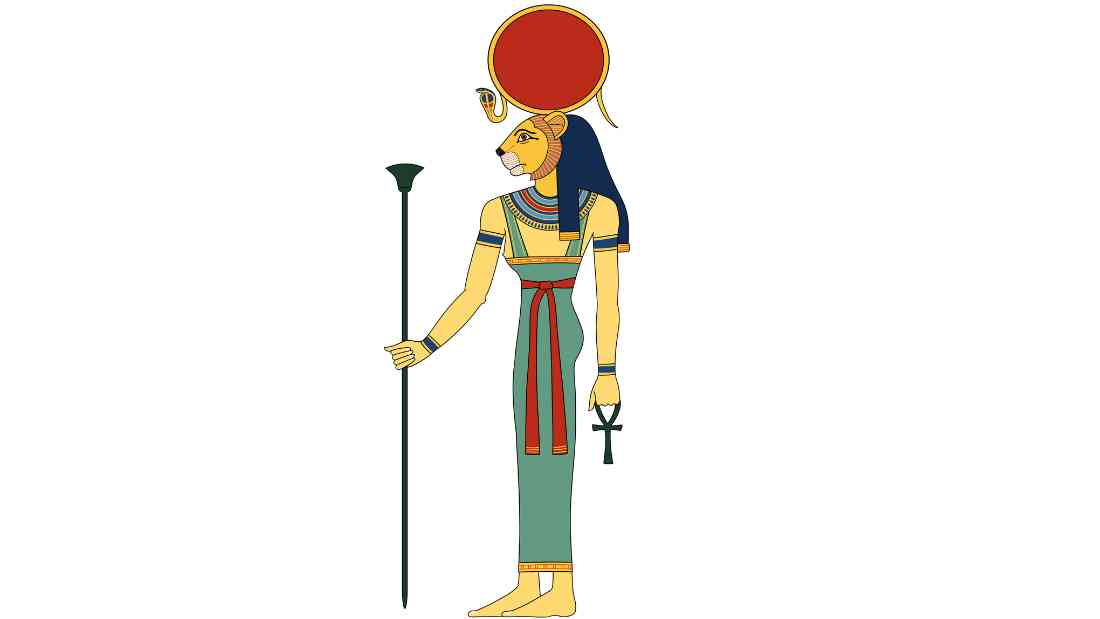

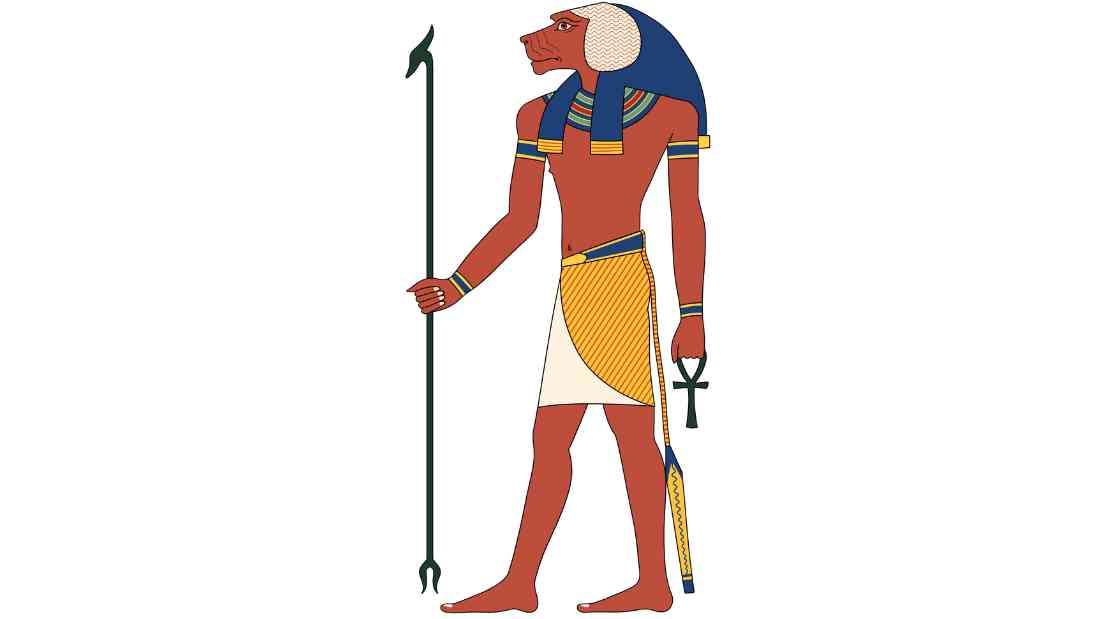

Depictions of Ra often feature him as a hawk-headed figure, a form chosen to signify his far-reaching vision and swift justice.

Above his head, a radiant sun disk, an emblem of his solar dominion, would invariably shine, casting its divine light on his subjects.

This iconography, while visually stunning, is more than mere artistic representation. It is a symbolic narrative of Ra’s omnipresence and his role as the supreme life-giver.

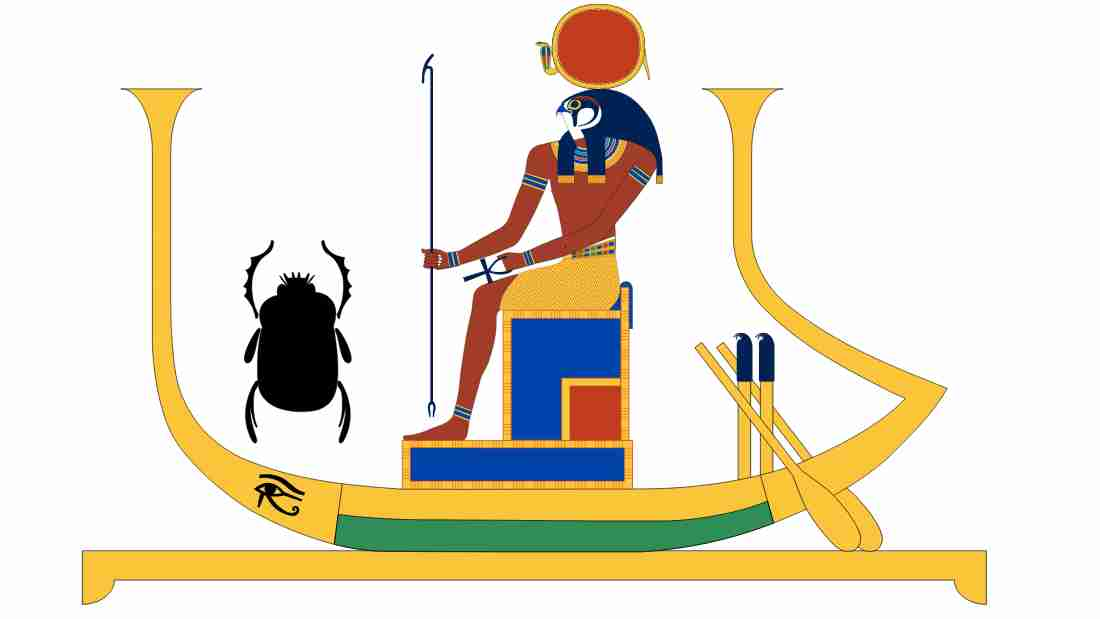

Ra’s daily journey across the sky, from dawn to dusk, was perceived as not only a physical phenomenon but also a spiritual one. It was seen as a continuous cycle of life, death, and rebirth, a timeless ritual that echoed the natural world’s own cyclical rhythms.

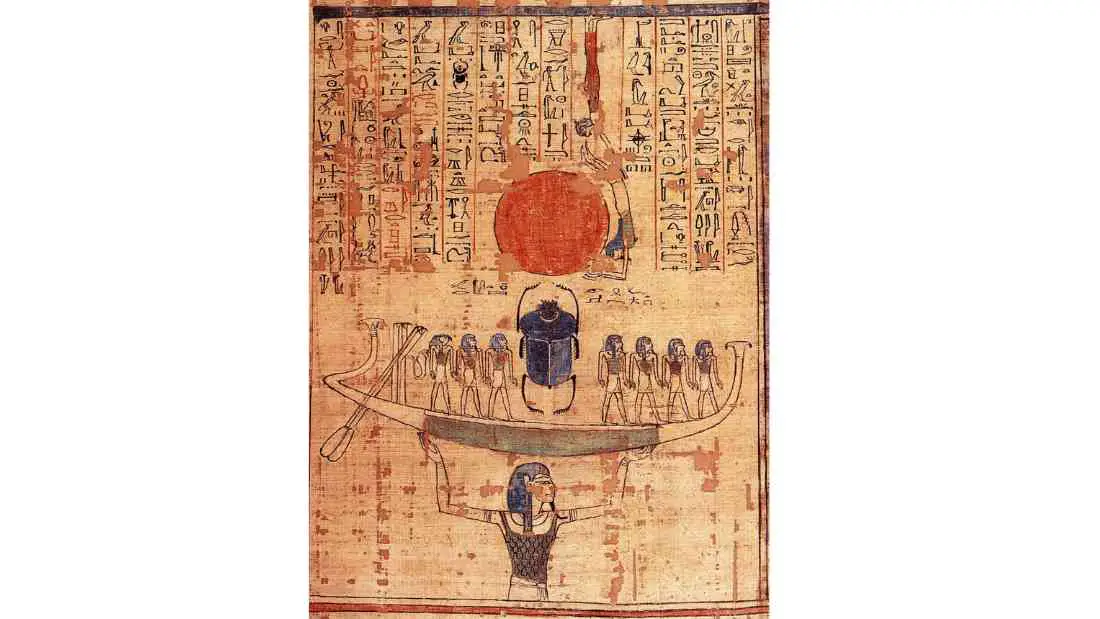

Each morning, Ra was believed to be reborn, emerging from the underworld in the form of Khepri, the scarab beetle god.

As he traversed the sky, he aged, embodying his noon form, ‘Ra at his zenith.’

By evening, he transformed into Atum, the aged version of himself, only to die and journey through the underworld, marking the cycle’s completion.

Moreover, Ra’s connection with creation is deeply rooted in ancient Egyptian cosmology.

He was believed to have emerged from the primordial waters of Nun, bringing forth the universe by speaking the names of all things. This act established Ra as a divine utterance’s embodiment, a cosmic force that wove the very fabric of existence.

The Pharaohs, seen as earthly embodiments of Ra, held their authority in his name. The concept of kingship was intrinsically tied to Ra, further reinforcing his central role in the social and religious constructs of ancient Egypt.

In this way, Ra, the majestic sun god, was more than a deity. He was a symbol of the unyielding power of the sun, the cyclical nature of life, and the divine authority of the pharaohs.

His influence permeated every aspect of ancient Egyptian life, making him one of the most significant figures in their rich mythological tapestry.

Khepri – The Reborn Version of Ra and Scarab Beetle God of Creation and Rebirth

Khepri, the god often depicted as a scarab beetle or a man with a beetle head, symbolizes creation, rebirth, and the sun’s daily journey, embodying the transformative powers of life and the cyclical nature of existence.

The scarab beetle, the creature that represents Khepri, holds a profound symbolic meaning in the pantheon of ancient Egyptian gods. It is associated with the cycle of life, death, and rebirth due to its behavior of rolling balls of dung across the earth, which it later uses as a food source and breeding ground.

This action mirrors the sun’s daily journey across the sky, leading to the association of Khepri with the rising sun and the creation of life.

As the god of creation, Khepri is believed to have formed the world and all its creatures.

In some mythological narratives, he is said to renew the sun every day before rolling it above the horizon, then carrying it through the other world after sunset, only to renew it once again the next day.

This daily cycle of birth, death, and rebirth underscores his role as a deity of transformation and renewal.

Khepri’s influence also extends to the realm of human life, where he is seen as a protector and guide for the souls journeying through the afterlife. His image was frequently used in funerary art and amulets, providing comfort and guidance to those crossing into the afterlife.

Moreover, Khepri’s representation as a scarab beetle is also linked to the concept of resurrection. Just as the beetle emerges from its ball of dung, so too do the ancient Egyptians believe in the possibility of life emerging from death, further emphasizing Khepri’s role as the god of rebirth.

Hence Khepri embodies the miraculous cycle of life, death, and rebirth. His representation as a humble yet industrious insect that plays a crucial role in maintaining the balance of nature serves as a potent symbol of the transformative and cyclical powers of life.

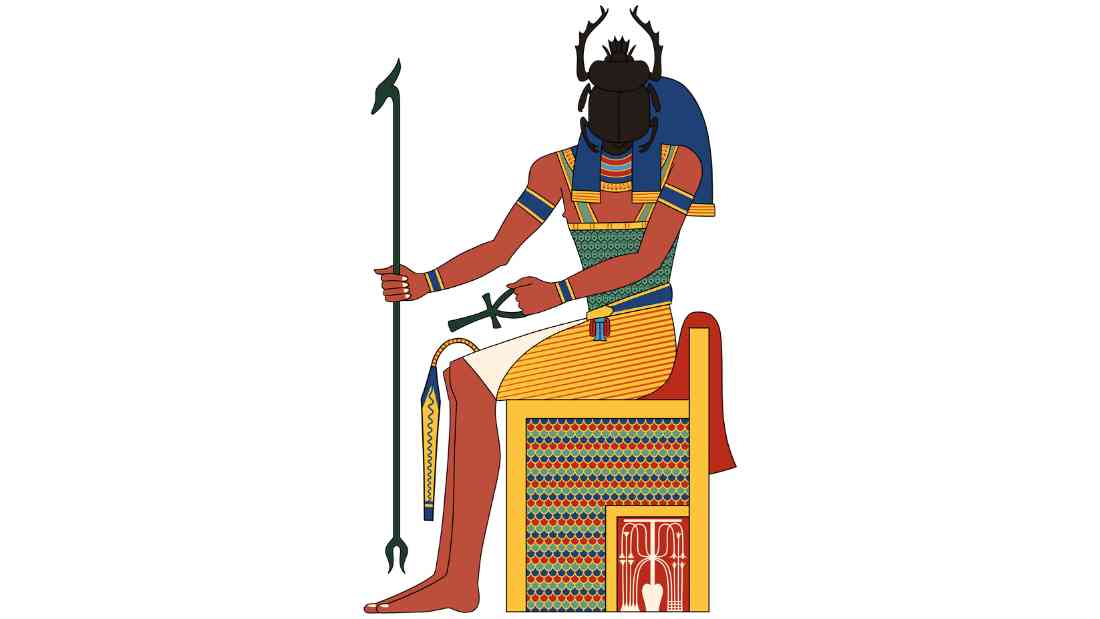

Atum – The Aged Incarnation of Ra and the God of Completion

Atum, the aged version of the sun god Ra, is the god of completion and the setting sun.

He embodies the concept of endings, transitions, and the cyclical nature of time.

The name Atum comes from the term ‘tem’ which means ‘to complete’ or ‘to finish’ in ancient Egyptian. This etymology reflects his association with the end of the day when the sun sets and the world transitions into night.

While Ra represents the sun at its zenith, full of life-giving energy and warmth, Atum symbolizes the sun as it descends below the horizon, marking the end of the day and the beginning of the night.

Atum’s role as the aged version of Ra further underscores his connection with the cycle of time. He is often depicted as an old man or a man with the head of a lion, signifying his wisdom and strength even in old age.

In this form, he represents the later stages of life and the transition into the afterlife, symbolizing the completion of one’s earthly journey.

As the god of completion in the pantheon of ancient Egyptian gods, Atum also plays a crucial role in creation myths.

According to Egyptian narratives, Atum was the first god to exist, emerging from the primordial waters of Nun. From him, all other gods and all of creation sprang forth.

Thus, he represents both the beginning and the end, the alpha and omega of existence.

Moreover, Atum’s association with the setting sun also links him to concepts of regeneration and rebirth. Just as the sun sets to rise again, so too does Atum embody the promise of new beginnings following endings, reinforcing the cyclical nature of life and time.

Nebethetepet – The Hand of Atum

Nebethetepet personifies the hand of Atum, the creator god who brought the universe into existence according to Heliopolitan cosmology. She was worshipped primarily at Heliopolis, one of the oldest cities of ancient Egypt.

In this unique role, Nebethetepet represents the active, feminine principle of Atum.

In many ancient cultures, including Egypt, hands symbolize creation, action, and purpose.

As such, Nebethetepet”s association with the hand of Atum underscores her role in the act of creation.

Despite being a lesser-known figure compared to other ancient Egyptian gods and goddesses, Nebethetepet played a crucial part in the ancient Egyptian understanding of the cosmos.

Her existence is a testament to the balance that the ancient Egyptians saw in the universe – a balance between male and female, action and stillness, creation and destruction.

Moreover, Nebethetepet’s association with Atum highlights the complexity and intricacy of ancient Egyptian religious beliefs. The Egyptians often viewed their gods as having multiple aspects, each represented by different deities. Nebethetepet, as the personification of Atum’s hand, is a prime example of this multifaceted approach to divine entities.

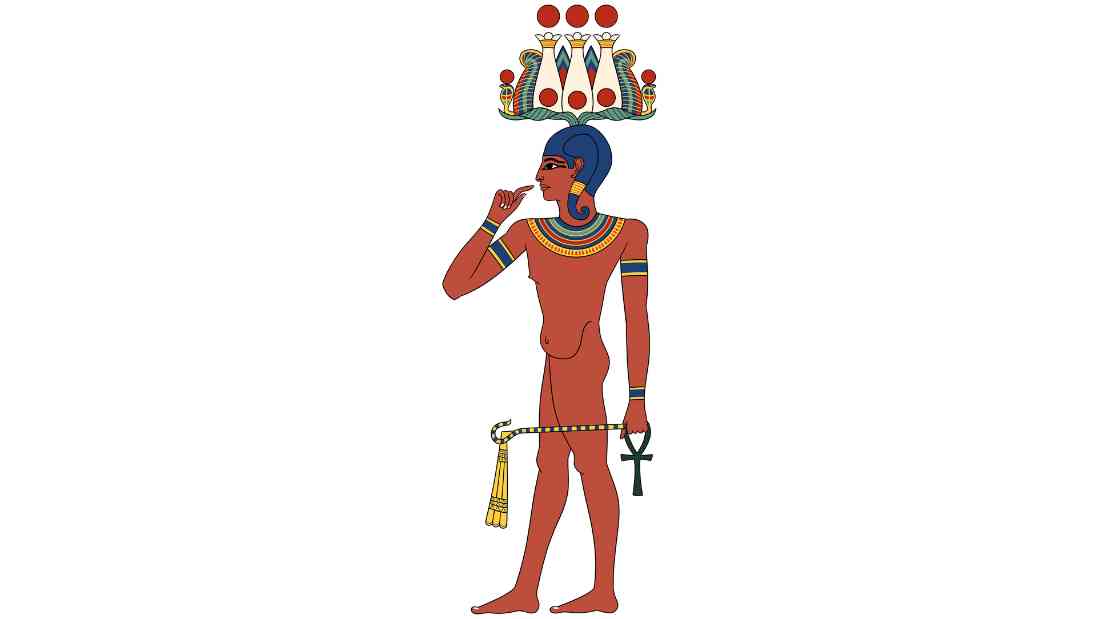

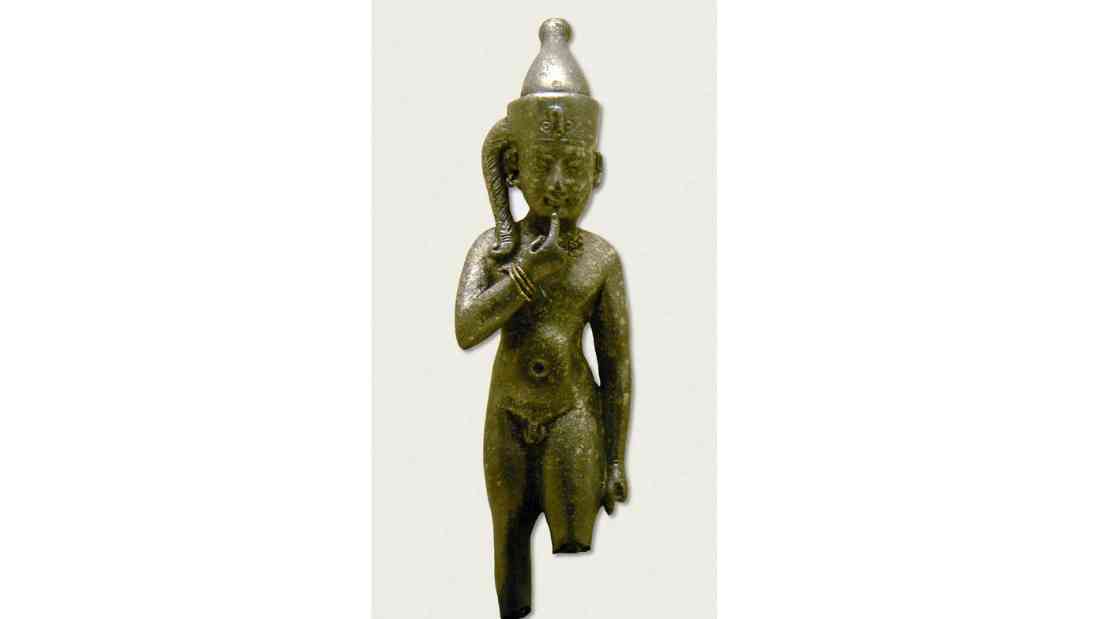

Nefertum – The God of Perfume and Sweet Aromas

Nefertum, also known as Nefertem, is the god of perfume and sweet aromas, embodying the allure and transformative power of scent.

His story begins at the dawn of creation, emerging from the bud of the blue lotus flower, a symbol of the sun, rebirth, and regeneration in ancient Egyptian culture.

Originally, Nefertum was considered an aspect of Atum, the creator god in Heliopolitan cosmology. His name, which translates to “Beautiful Atum,” reflects this early connection.

However, over time, Nefertum evolved into a distinct deity in his own right, becoming closely associated with sweet-smelling flowers.

Beyond his association with pleasant fragrances, Nefertum also embodies concepts of rebirth and transformation.

His link to the sun god and flowers symbolizes renewal and change, mirroring the daily journey of the sun and the cyclical blooming of flowers.

This association made Nefertum an important figure in ancient Egyptian rituals related to rebirth and rejuvenation.

In the realm of Egyptian medicine, Nefertum’s role extended to healing and disease prevention.

He was often invoked for his healing aromas, which were believed to cure diseases and restore health.

Incense, a common offering in ancient Egyptian religious practices, was also closely associated with Nefertum due to its fragrant smoke.

Bennu – The Divine Bird of Creation

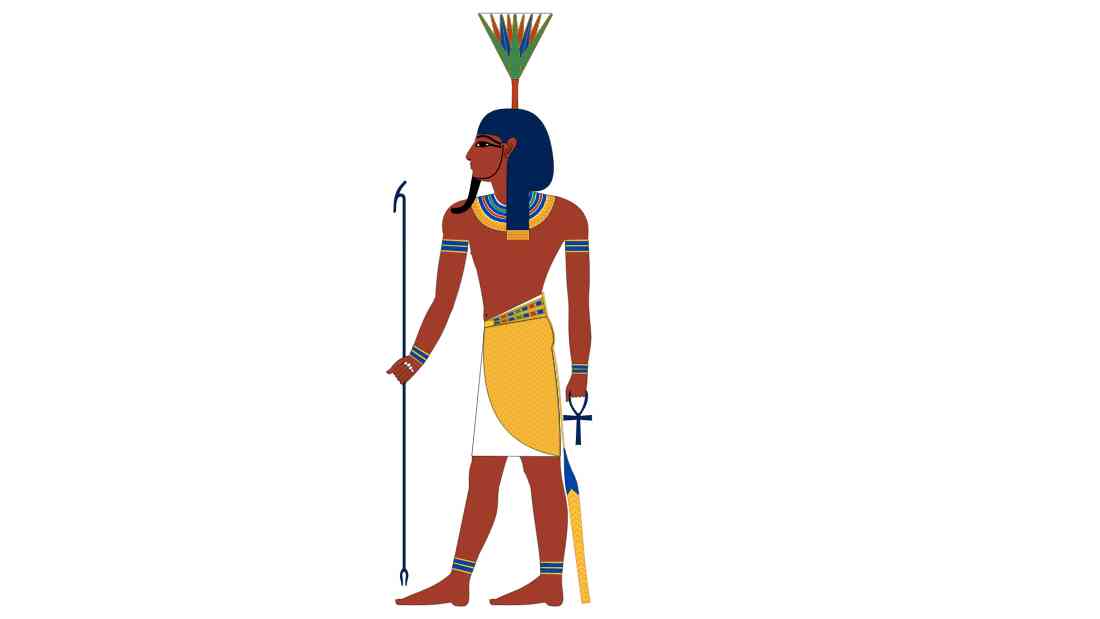

Bennu, also known as the Bennu Bird, is an avian deity associated with creation, rebirth, and renewal. Visually, it was often depicted as a heron or a similar type of bird, with a two-feathered crest on its head.

This image became a potent symbol of rebirth and regeneration, which was used extensively in ancient Egyptian art and iconography.

The Bennu Bird’s association with creation originates from its link to Atum, the sun god and the creator deity in Heliopolitan cosmology.

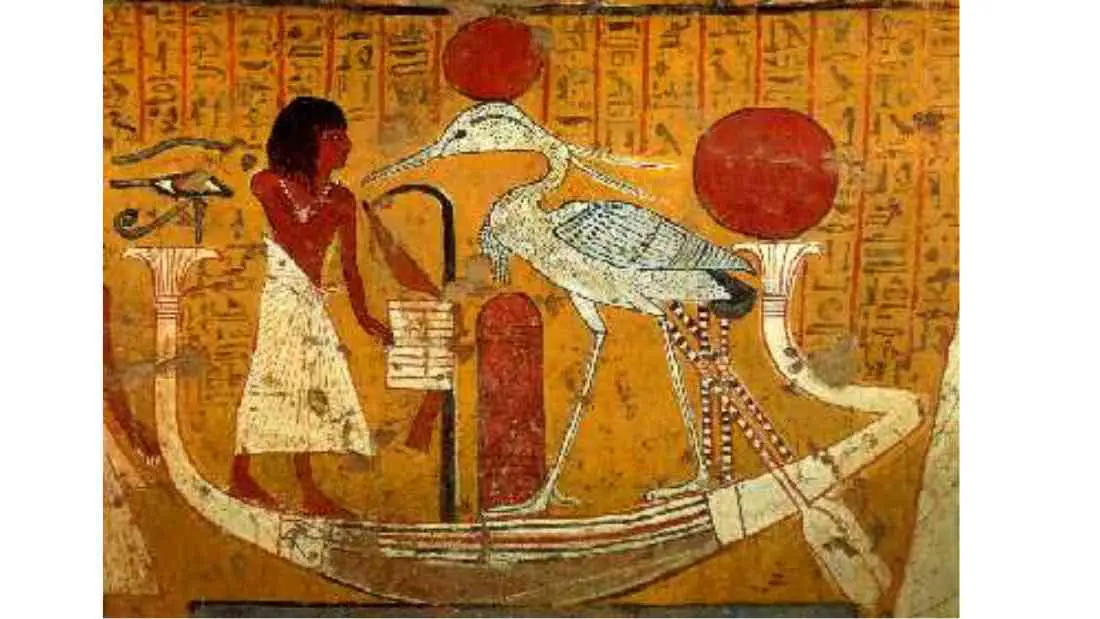

According to one creation myth, the Bennu Bird flew over the waters of Nun, the primordial chaos, before the world was created. Its cry broke the silence, marking the beginning of time and the creation of the world.

The Bennu Bird was also closely associated with Ra, the sun god. It was believed to have created itself from a fire that burned on a holy tree in one of Ra’s sacred precincts. This self-creation resonates with the qualities of the sun, which ‘dies’ every night and ‘rebirths’ every morning, further reinforcing Bennu’s connection with renewal and rebirth.

Moreover, Bennu was also linked with Osiris, the god of the dead and resurrection. In this context, Bennu symbolized the promise of eternal life in the afterlife.

Representations of the Bennu Bird were often found in tombs and burial sites, providing the deceased with the assurance of rebirth and immortality.

The Bennu Bird inspired the concept of the Phoenix in Greek mythology, a bird that cyclically regenerates and symbolizes rebirth and renewal.

Apep (Apophis) – The Celestial Serpent and Nemesis of Ra

Apep, also known as Apophis, is a formidable figure in ancient Egyptian mythology.

As a celestial serpent, Apep represents the antithesis of order and light, embodying chaos and darkness. His primary role in the mythological narrative involves his nightly assault on the sun barge of Ra, the sun god.

Ra’s sun barge, representing the sun’s journey across the sky, moves through the underworld each night, symbolizing the transition from day to night.

This journey isn’t peaceful; it’s fraught with danger, primarily due to Apep’s relentless attacks. The celestial serpent’s aim is to disrupt the cycle of day and night, thereby plunging the world into eternal darkness.

This epic battle between Apep and Ra is more than just a struggle between two powerful deities. It symbolizes the eternal conflict between order and chaos, light and darkness, good and evil.

In this cosmic drama, Ra stands for order and stability, while Apep embodies the forces that seek to disrupt this harmony.

During their epic battles, the sun god is aided by other gods and the justified dead – those souls deemed worthy in the afterlife. These allies help fend off Apep, ensuring the sun’s journey continues and dawn arrives as it should.

Isis – Goddess of Magic and Healing

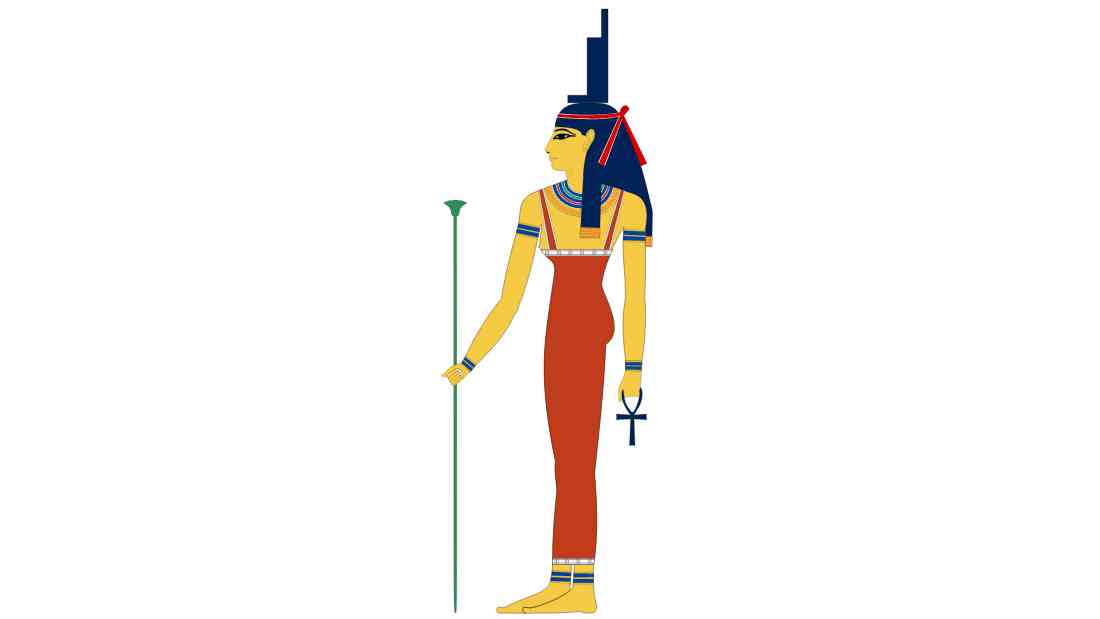

Isis, an eminent deity in the ancient Egyptian pantheon, was a multifaceted goddess embodying fertility, magic, healing, and motherhood.

Revered for her benevolence and caring nature, she was a beacon of hope and comfort to her followers, offering spiritual succour and protection through her magical prowess.

As the goddess of magic, Isis was believed to possess immeasurable knowledge of mystical arts. She was said to have used her enchanting abilities to aid humans, offering them relief from ailments, protection from evil forces, and guidance in times of uncertainty.

Her magic was deeply intertwined with her role as a healer, and she was often invoked in rituals aimed at curing diseases or warding off misfortune.

Isis was also hailed as the quintessential mother goddess, a symbol of fertility and the sanctity of maternal bonds.

She was revered as the divine protector of children and women, particularly during childbirth. Her nurturing aura extended to agriculture, where she was associated with the fertile lands nurtured by the Nile’s annual flooding.

This goddess of many talents was easily recognizable by her iconic throne-shaped headdress, a symbol of her power and status.

The throne motif was more than just a royal emblem. It symbolized Isis’s role as the provider of kings and her influence in the earthly realm’s governance.

Integral to Isis’s mythological narrative is her relationship with Osiris, her husband, and Horus, her son.

As the wife of Osiris, the god of the underworld, Isis demonstrated her unwavering loyalty and love by seeking his body after his brother Set murdered him.

Using her potent magic, she resurrected Osiris long enough to conceive their son, Horus. This act further cemented her association with rebirth and regeneration.

As the mother of Horus, the sky god and the divine representation of the pharaohs, Isis played a crucial role in royal succession’s divine validation.

She was seen as the nurturer of divine kingship, further amplifying her importance in the socio-religious fabric of ancient Egypt.

Arensnuphis – The Nubian Companion of Isis

Arensnuphis is known primarily as a companion to the goddess Isis. His origins trace back to Nubia, a region along the Nile river, which is located in what is now southern Egypt and northern Sudan.

This Nubian connection adds a layer of cultural richness to Arensnuphis’s character and role within the mythological narrative.

Isis, one of the most important and widely worshipped deities in ancient Egypt, is associated with motherhood, magic, and healing.

As her companion, Arensnuphis shares in her divine duties and responsibilities.

Together, they form a powerful pair, embodying a range of qualities and attributes revered by the ancient Egyptians.

Arensnuphis was worshipped primarily at Philae, a sacred site dedicated to Isis.

This island in the Nile was home to a magnificent temple complex where rituals and ceremonies honoring Isis and her companion were regularly performed.

Here, Arensnuphis was venerated alongside Isis, reinforcing his importance within the pantheon of ancient Egyptian gods.

Depictions of Arensnuphis vary, reflecting the multifaceted nature of his persona.

He is often portrayed as a lion, a symbol of power and protection in Egyptian iconography.

Alternatively, he may be depicted as a man wearing a feathered headdress, an emblem of divinity and authority. These visual representations underscore Arensnuphis’s divine status and his close association with Isis.

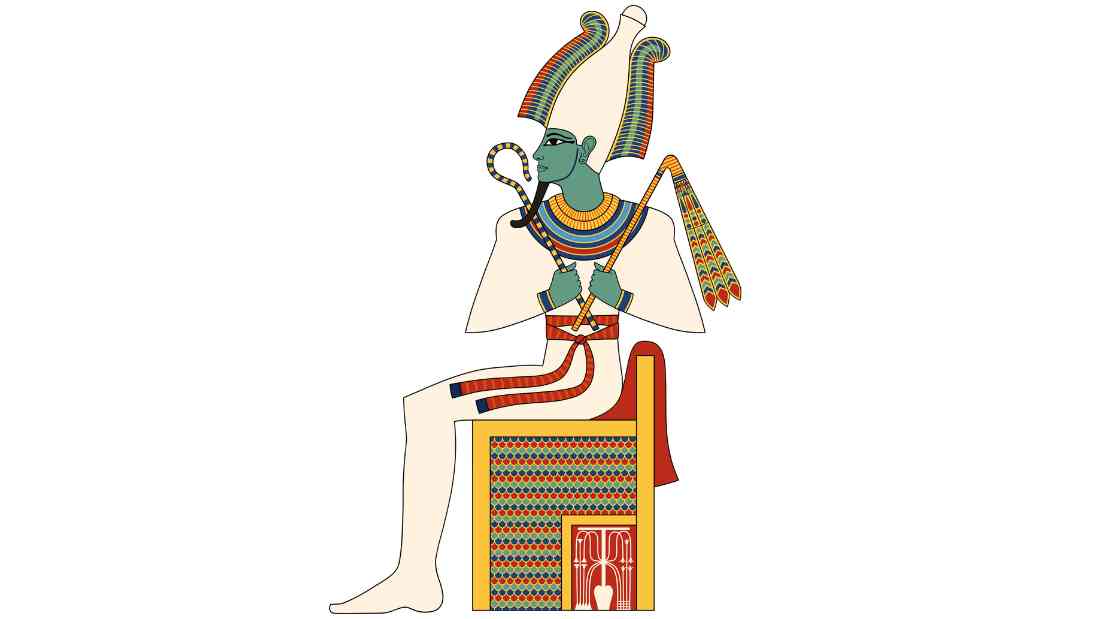

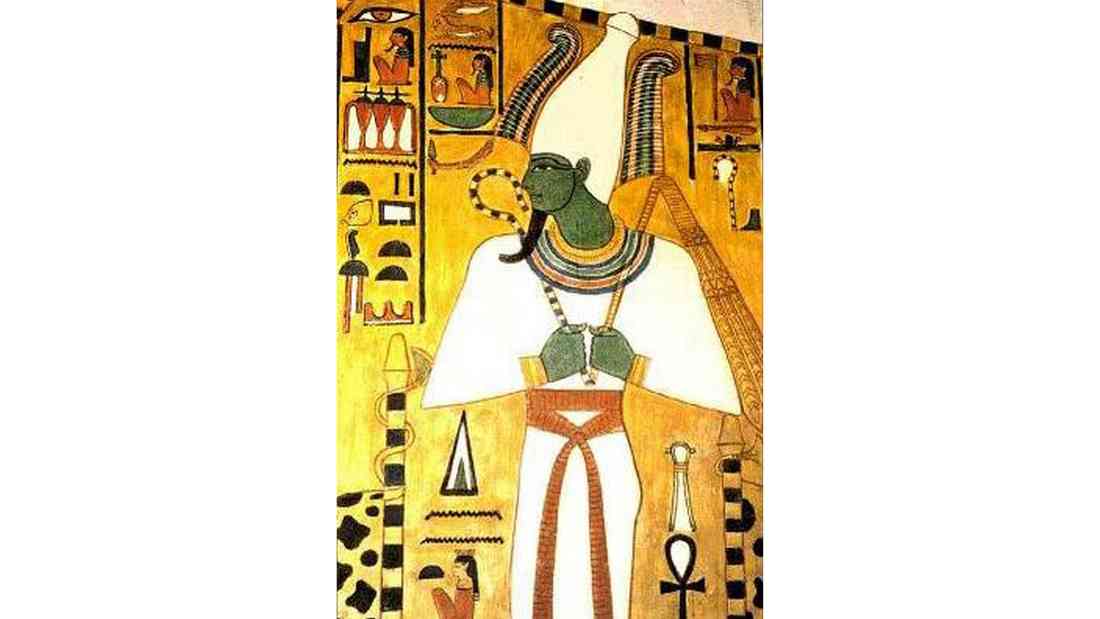

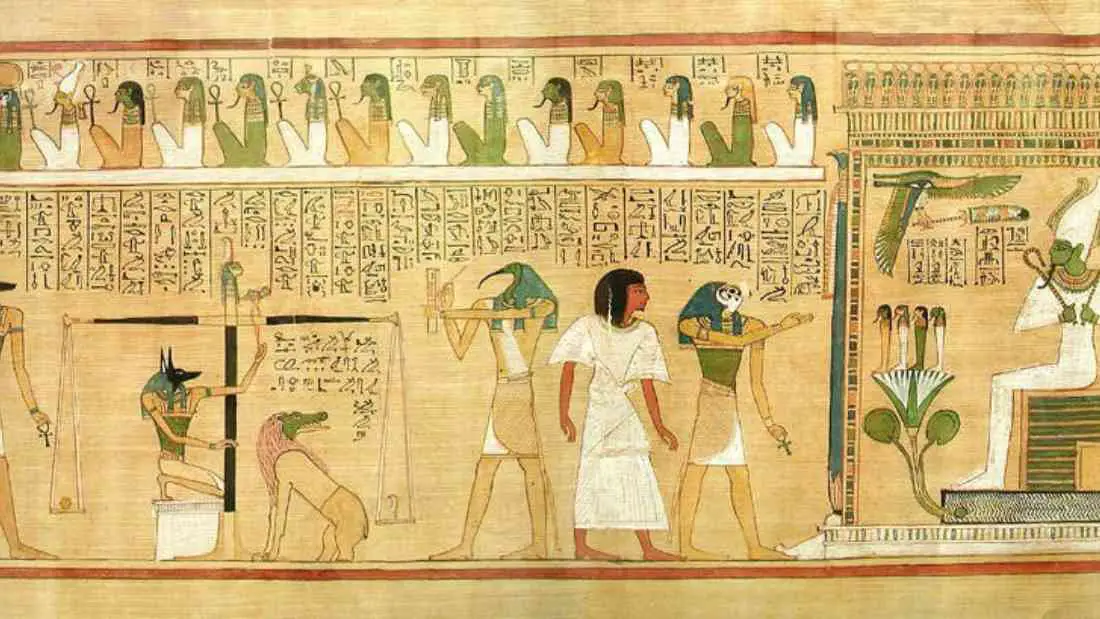

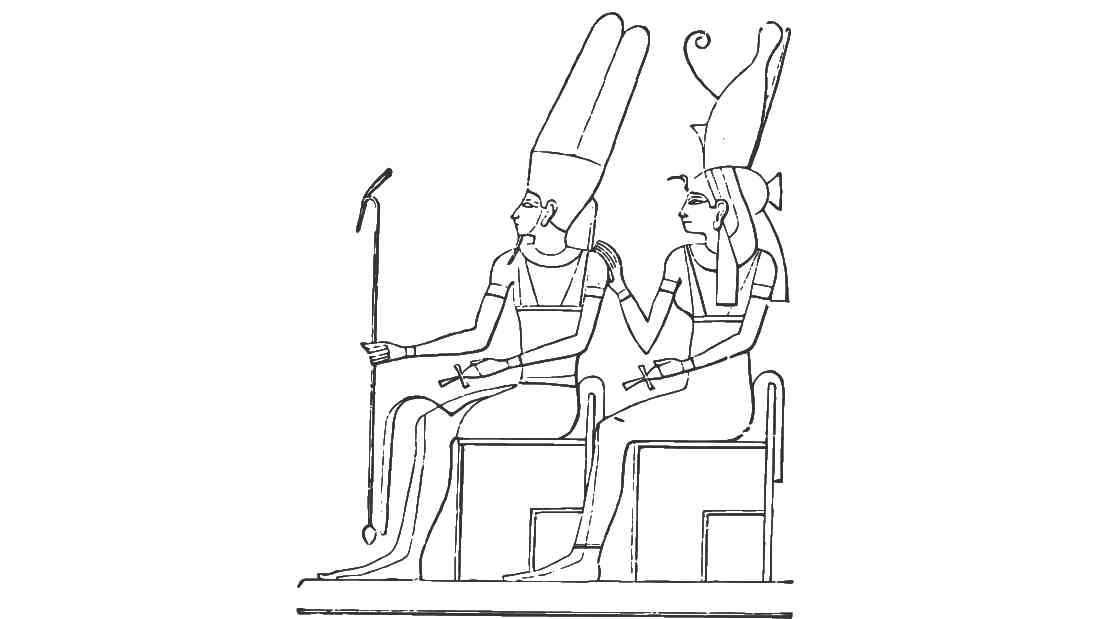

Osiris – God of the Underworld

Osiris, the enigmatic god presiding over the underworld is a central figure within the intricate tapestry of ancient Egyptian gods.

Depicted as a green-skinned man wrapped in mummy bandages, Osiris was a visual testament to the concepts of renewal and regeneration.

The green hue of his skin was not an arbitrary choice. It symbolized vitality and the verdant bounty of the earth, mirroring the fertile lands left behind by the receding Nile floods.

This iconography underscored Osiris’s strong connection to the natural world and its cyclical patterns of death and rebirth.

Beyond his underworld dominion, Osiris was also deeply intertwined with the annual Nile flood.

The Egyptians saw these floods, which enriched the soil and ensured bountiful harvests, as a manifestation of Osiris’s benevolence.

The inundation was seen as a divine act of rejuvenation, echoing Osiris’s own narrative of death and resurrection.

Osiris’s mythological narrative is incomplete without mentioning his relationship with Isis, his devoted wife, and Horus, his posthumous son.

Osiris’s murder by his brother Set and subsequent resurrection by Isis is one of ancient Egyptian mythology’s most enduring tales. It not only cements Osiris’s association with resurrection but also underlines the themes of loyalty, betrayal, and familial bonds that are woven into the pantheon’s mythology.

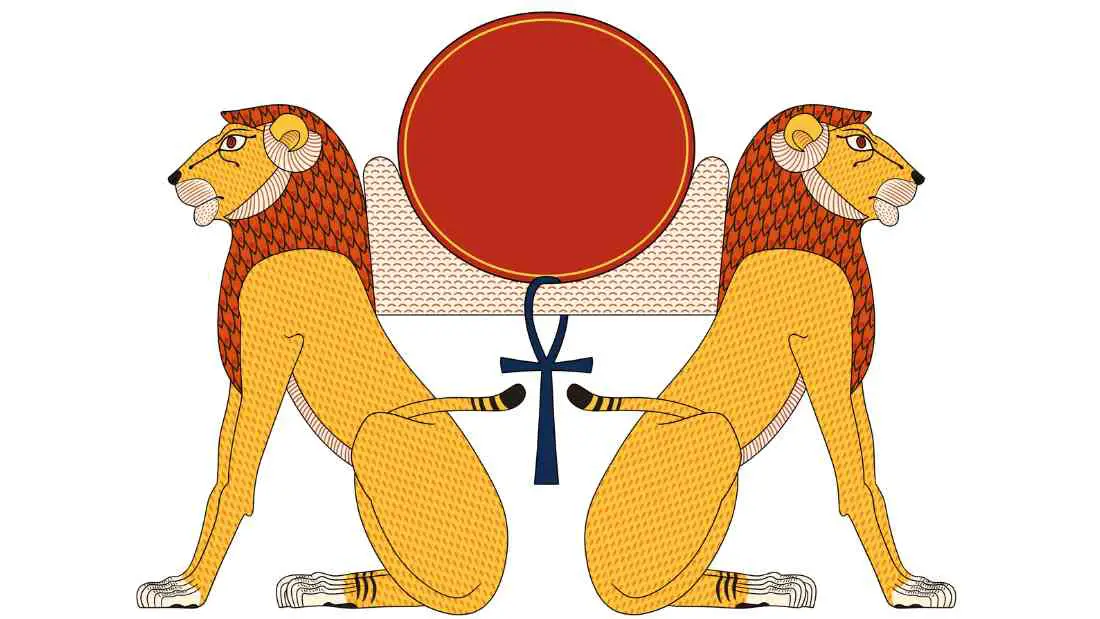

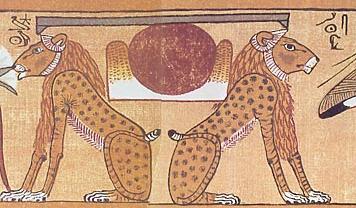

Aker – The Guardian of the Afterlife

Aker is the guardian of the eastern and western horizons of the afterlife.

He played a pivotal role in the protection of the sun barge of Ra, the sun god, as it ventured into and emerged from the underworld at dawn and dusk.

The name ‘Aker’ translates to ‘Earth,’ indicating his association with the terrestrial realm and its horizons.

Aker was often depicted as two lions sitting back-to-back, one representing yesterday (the west) and the other tomorrow (the east). This imagery symbolized Aker’s domain over the past and the future, and his role as the threshold between the realms of the living and the dead.

In ancient Egyptian cosmology, the journey of the sun god Ra across the sky was not just a daily event, but a cyclical narrative of death and rebirth.

As the sun set in the west, it was believed to descend into the underworld, marking Ra’s death. At dawn, when the sun rose in the east, Ra was reborn, signaling a new day.

Aker’s role was crucial in this process.

As the guardian of the horizons, he protected Ra’s sun barge from the dangers of the underworld as it entered at dusk and re-emerged at dawn.

Despite the perils present in the underworld, including the chaotic serpent Apophis, Aker ensured the sun’s safe passage, enabling the cycle of day and night to continue uninterrupted.

Aker’s protective function extended to the deceased as well.

Ancient Egyptians believed that the souls of the dead had to traverse the underworld to reach the afterlife. As the guardian of the horizons, Aker would protect these souls during their journey, much like he did for Ra.

Aken – Custodian of the Boat in the Afterlife

Aken, an important but often overlooked figure in ancient Egyptian mythology, is the guardian of the boat that carries souls across Lily Lake, also known as the Winding Waterway, to the Field of Reeds, the ultimate destination in the afterlife.

The name ‘Aken’ translates to ‘He Who is Effective,’ a fitting title for a deity who played such a crucial part in the spiritual journey of the deceased.

His role in the pantheon of ancient Egyptian gods was not merely that of a ferryman, but as a custodian, ensuring safe passage across the treacherous waters of the underworld.

Lily Lake, a central feature in ancient Egyptian cosmology, represented the hazardous journey that souls had to undertake after death. It was filled with dangerous creatures and obstacles. However, under Aken’s watchful guidance, the souls could traverse this challenging path to reach the Field of Reeds.

The Field of Reeds, also known as Aaru, was a heavenly paradise where souls could live an eternal life of peace and contentment, mirroring their earthly existence but without hardships or suffering. It was a place of abundance, filled with lush fields, magnificent buildings, and bountiful food and drink.

Aken is typically depicted as a man lying on his stomach atop a sarcophagus, symbolizing his connection with death and the afterlife. In other representations, he is shown standing on a boat, reinforcing his role as the divine ferryman. His image served as a comforting presence, assuring the ancient Egyptians of a secure passage to the afterlife.

Despite not being as widely venerated as some other Egyptian deities, Aken held a significant place in the pantheon due to his critical role in the soul’s journey after death.

His duty as the custodian of the boat to the Field of Reeds underscores the ancient Egyptians’ complex beliefs about death and the afterlife, portraying death not as an end, but as a transition to a new beginning.

Hraf-Hef – The Divine Ferryman

Hraf-Hef, a distinctive figure in ancient Egyptian mythology, is recognized as the surly divine ferryman responsible for transporting souls across the underworld’s perilous waters.

Unlike Aken, the custodian of the boat, Hraf-Hef is depicted as somewhat gruff and ill-tempered, yet his role in the spiritual journey of the deceased was just as vital.

The name ‘Hraf-Hef’ translates roughly to ‘He Who Looks Behind Himself,’ suggesting a cautious and wary nature, fitting for a deity charged with such a daunting task.

Despite his surly demeanor, Hraf-Hef was entrusted with ensuring the safe passage of souls through the challenging landscapes of the underworld to their final resting place.

In ancient Egyptian cosmology, the journey after death was fraught with danger and uncertainty. It was believed that the soul had to cross treacherous waters teeming with hostile creatures and navigate numerous obstacles before reaching the afterlife.

Hraf-Hef, with his stern demeanor and watchful eyes, was seen as the ideal guardian for this hazardous voyage.

Hraf-Hef is typically depicted as a man with a sour expression, often shown standing on a boat, reinforcing his role as the divine ferryman. This representation served not only as a symbol of his pivotal function in the afterlife journey but also as a reminder of the hardships and challenges that awaited the soul after death.

Despite his gruff exterior, Hraf-Hef was respected and revered for his crucial role in the journey to the afterlife. His stern countenance underscored the seriousness of the voyage, reminding the ancient Egyptians of the challenges that lay ahead in the afterlife.

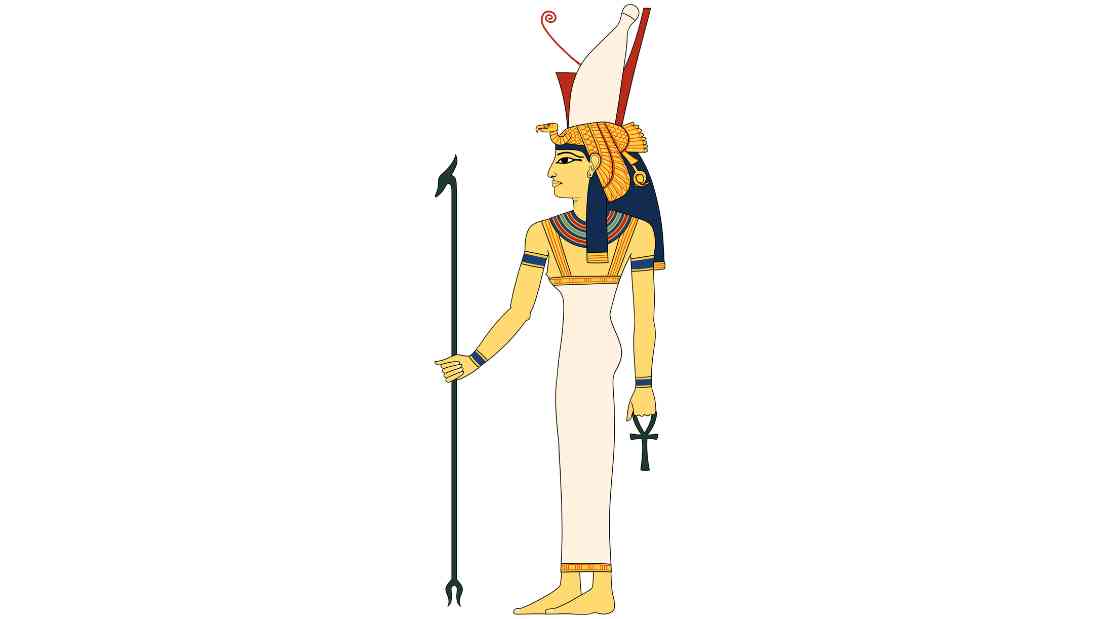

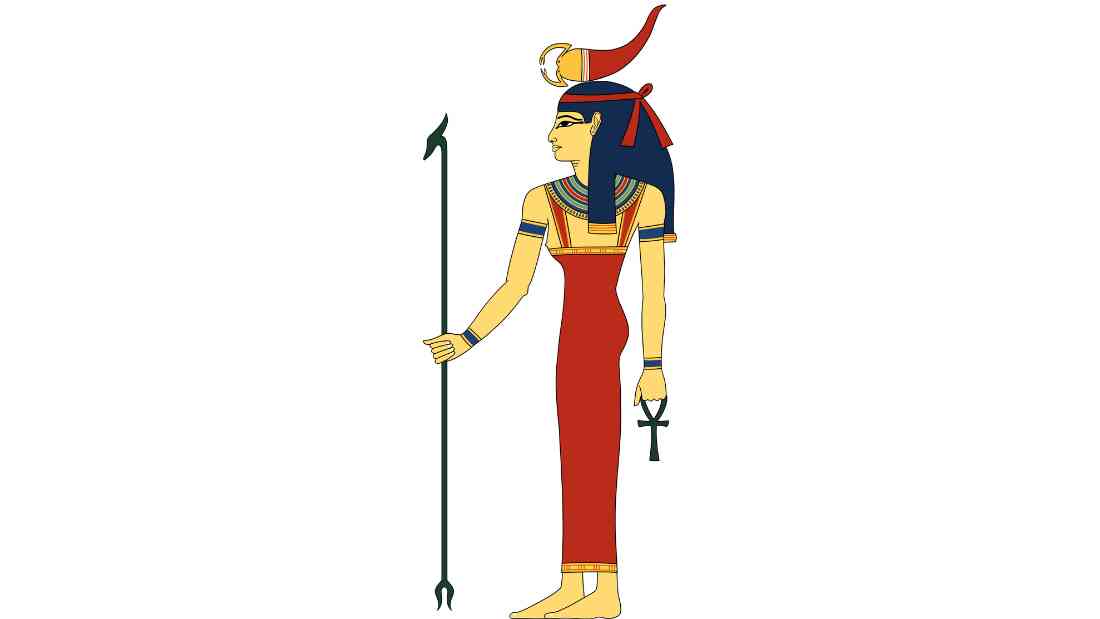

Amentet – The Welcoming Goddess of the Afterlife

Amentet is the goddess who welcomed the deceased to the afterlife.

Known as “She of the West,” in reference to the setting sun and the journey of the dead, Amentet was the consort of the Divine Ferryman and resided near the gates of the underworld.

Amentet’s name translates to ‘The Westerner,’ further emphasizing her association with the afterlife, which was believed to be located in the west where the sun sets.

As a welcoming deity, Amentet greeted the souls of the deceased with food and drink, providing them with sustenance for their journey in the afterlife.

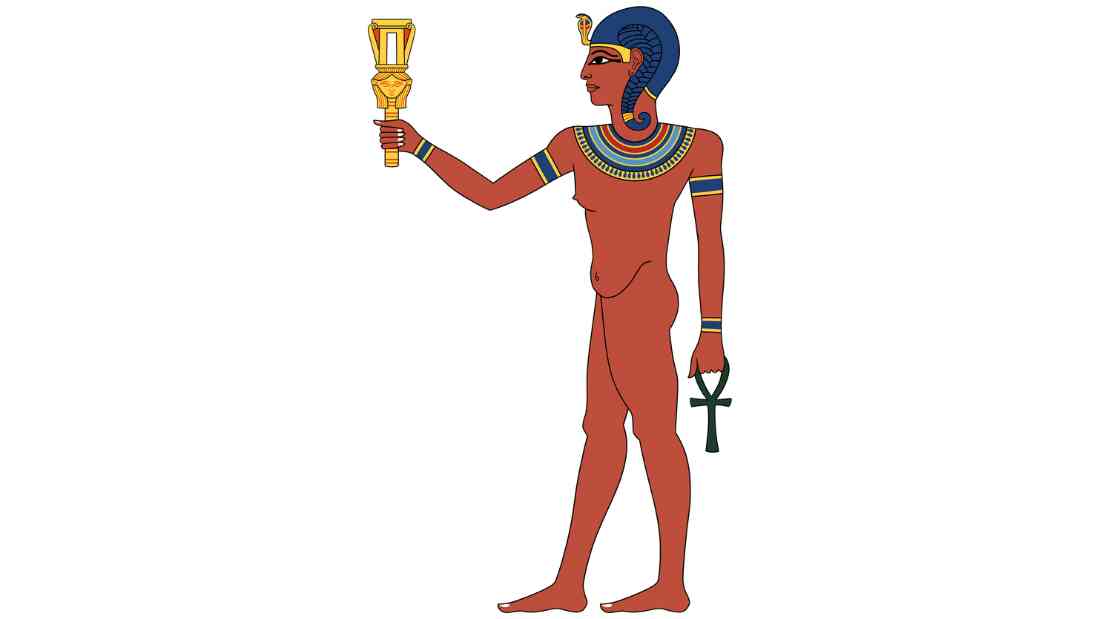

In ancient Egyptian art, Amentet is often depicted bearing a scepter symbolizing authority and an Ankh, the Egyptian symbol of life.

She is frequently shown under a tree, signifying her abode near the gates of the underworld.

This tree, according to some legends, was thought to bear fruit that could grant eternal life, further linking Amentet with notions of immortality and the afterlife.

As the daughter of Hathor, the goddess of love, beauty, and music, and Horus, the god of the sky, Amentet inherited a divine lineage that underscored her significant role in the pantheon of ancient Egyptian gods.

Her relationship with the Divine Ferryman added another layer to her importance, symbolizing the harmonious union between the journey to the afterlife and the welcome that awaited the souls upon their arrival.

Despite the fear associated with death and the afterlife, the presence of Amtenet provided comfort and reassurance to the ancient Egyptians. Her welcoming nature and the sustenance she offered signified a compassionate reception in the afterlife, assuaging fears of the unknown and providing hope for a peaceful existence beyond death.

Kabechet – The Celestial Serpent and Funerary Deity

Kabechet, also known as Kebehwet or Qebhet, is an ancient Egyptian goddess whose mythology comes with a fascinating evolution.

Her origins trace back to the celestial sphere, where she was initially revered as a serpent deity. Over time, her image transformed, and she became more closely associated with funerary rites.

Kabechet is often regarded as the daughter of Anubis – the god of embalming and the dead. This familial connection further solidified her role within the realm of death and afterlife.

Despite her ominous associations, Kabechet is not a deity of darkness or malice. Instead, she represents comfort and purification for the deceased.

One of Kabechet’s most important roles was to provide pure, cool water to the souls of the deceased as they awaited judgment in the Hall of Truth.

This sacred place, also known as the Hall of Two Truths, was where the hearts of the deceased were weighed against the feather of Ma’at, the goddess of truth and justice.

The water provided by Kabechet was not merely for physical thirst. It was symbolic of spiritual cleansing and renewal, preparing the souls for their impending judgment.

This act of kindness amidst such a daunting process painted Kabechet as a compassionate figure, providing solace in a time of uncertainty.

Thus, Kabechet’s evolution from a celestial serpent to a funerary deity reflects the complex dynamics of ancient Egyptian mythology. She is a symbol of the comforting presence that can be found even in the most intimidating aspects of existence – death and the afterlife.

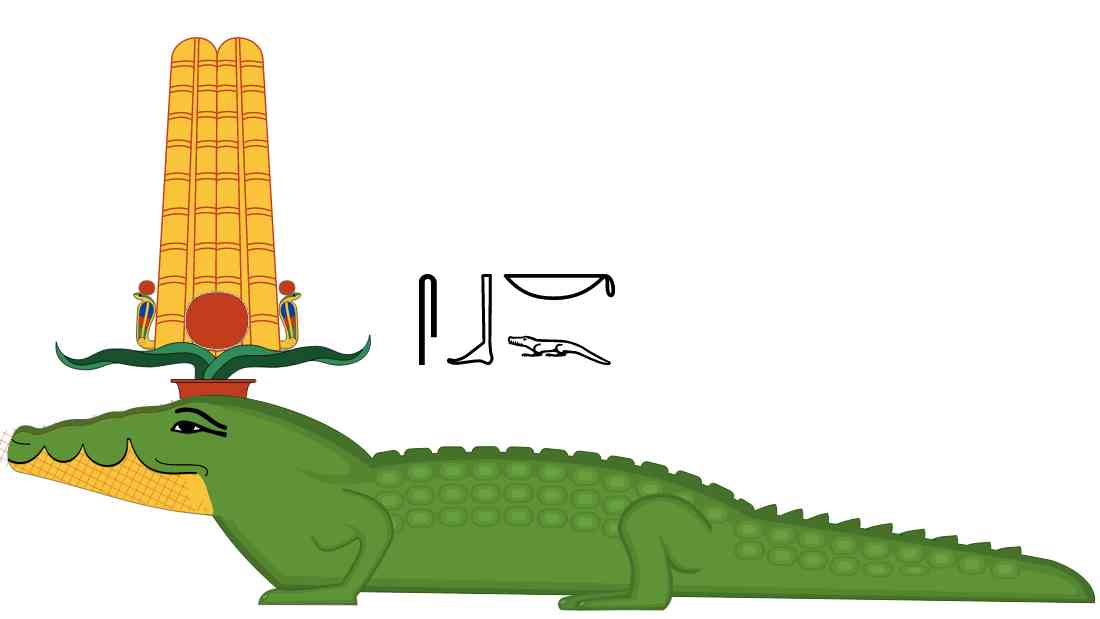

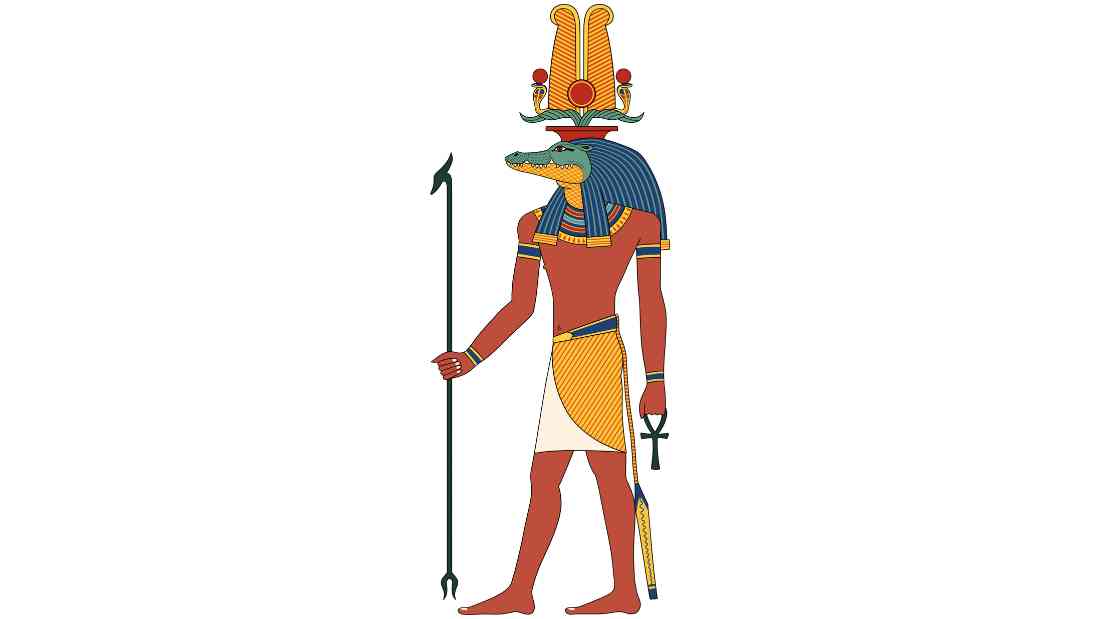

Sobek – Guardian of Pharaohs and Protector of the Nile and Fertility

Sobek, the mighty deity of ancient Egypt, was revered as the Guardian of Pharaohs and Protector of the Nile and Fertility. This formidable god embodied the power and ferocity of a crocodile, symbolizing the Nile’s dangerous yet life-sustaining waters.

Depicted with the head of a crocodile and the body of a human, Sobek commanded respect and awe among the people of Egypt.

He was believed to possess great strength, intelligence, and cunning, qualities that made him an ideal protector against threats to the pharaohs and the rich agricultural lands along the Nile.

As the Guardian of Pharaohs, Sobek was tasked with safeguarding the rulers of Egypt, ensuring their safety and prosperity.

It was believed that he could ward off evil forces, protect against enemies, and grant the pharaohs the strength and guidance they needed to lead their kingdom.

Additionally, Sobek played a vital role in maintaining the fertility and abundance of the Nile.

As the Protector of the Nile and Fertility, he oversaw the river’s annual flooding, which brought nutrient-rich silt to the surrounding farmland, allowing crops to flourish.

The ancient Egyptians saw Sobek as the force that controlled this life-giving cycle and relied on his blessings for bountiful harvests.

Sobek was worshipped throughout Egypt, with temples dedicated to him in various cities, such as Arsinoe and Kom Ombo. Rituals, offerings, and prayers were performed to honor and appease this mighty deity, seeking his favor and protection.

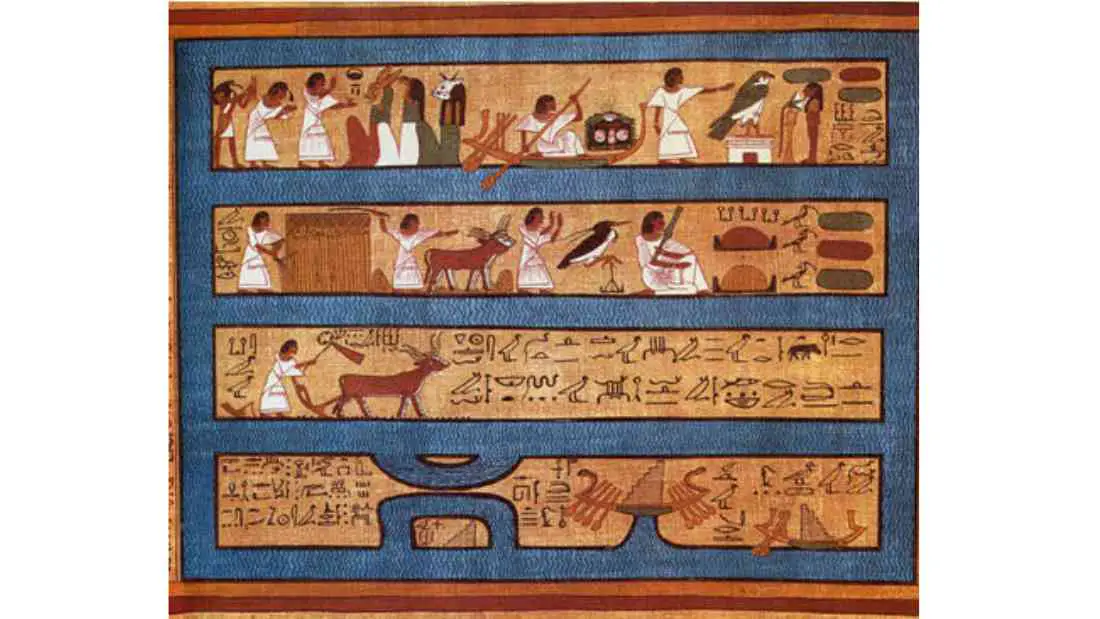

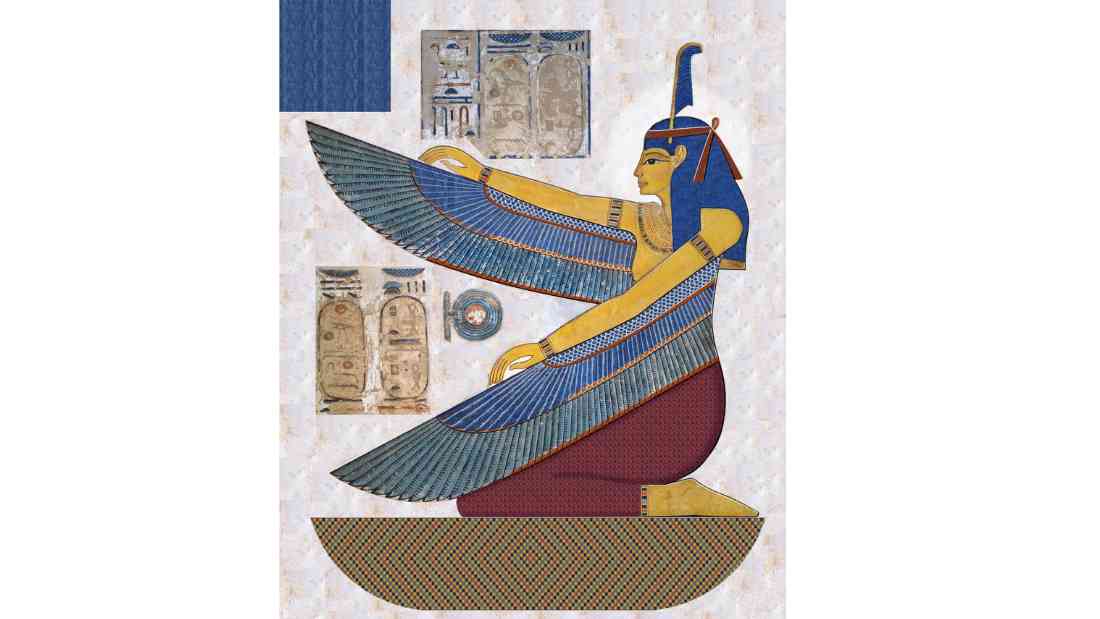

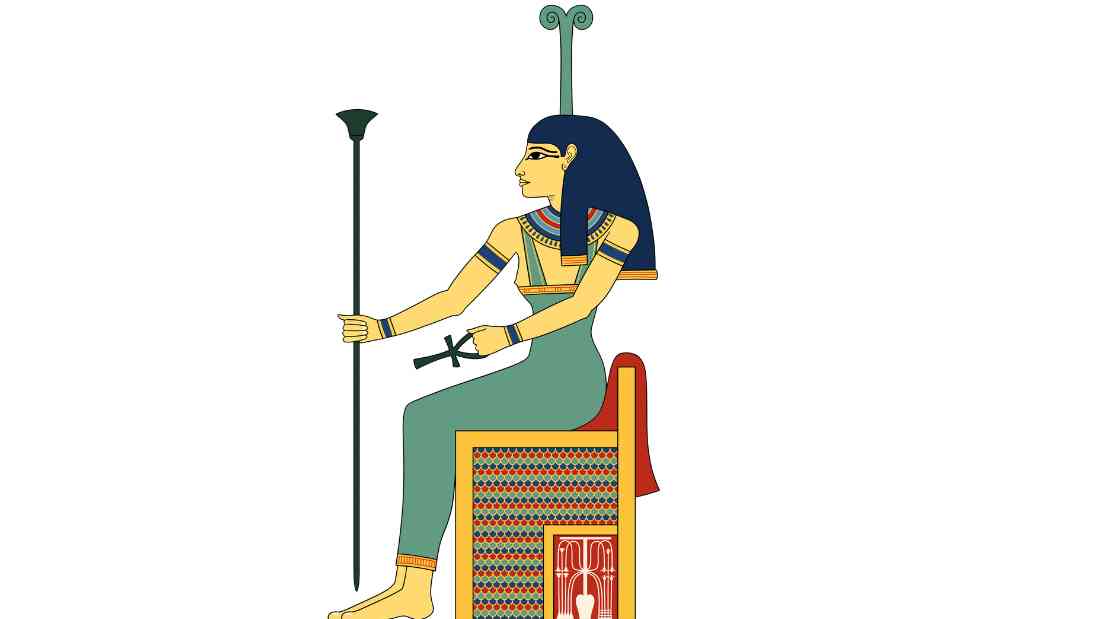

Ma’at – The Goddess of Truth, Justice, and Harmony

Ma’at is one of the most significant deities in ancient Egyptian mythology, embodying truth, justice, and harmony.

Her role extended beyond that of a traditional goddess. She represented the fundamental principle of ma’at, a concept central to the culture and worldview of ancient Egypt.

The principle of ma’at encompassed a broad range of meanings, including truth, balance, order, law, morality, and justice.

It signified the harmonious functioning of the universe, the ethical conduct of individuals, and the just operation of society.

As such, Ma’at was not only a goddess but also an embodiment of these essential ideals.

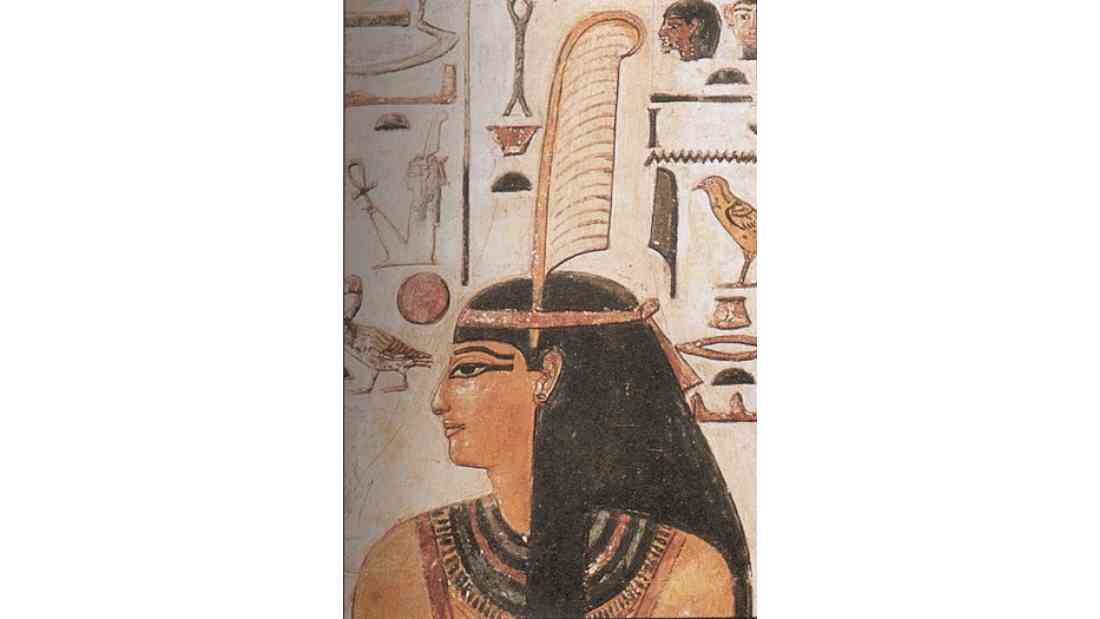

In ancient Egyptian art, Ma’at is often depicted with an ostrich feather on her head, which symbolizes truth. This feather played a crucial role in the judgment of the deceased in the afterlife.

In the Hall of Truth, the hearts of the dead were weighed against Ma’at’s feather. If the heart was lighter or equal in weight to the feather, the soul was granted eternal life. If it was heavier, it was devoured by Ammit, the “Devourer of Souls.”

This ritual underscores the significance of living a life of truth and morality in accordance with the principle of ma’at.

Ma’at’s influence extended to the cosmos as well. She was believed to set the stars in the sky and regulate the seasons, ensuring the orderly progression of time and the natural world. This cosmic role further emphasized the principle of ma’at as the foundation of harmony and balance in the universe.

In the pantheon of Egyptian gods, Ma’at held a unique position. She was the daughter of Ra, the sun god, and wife of Thoth, the god of wisdom and writing. Her familial ties linked her directly with the divine forces responsible for the creation and maintenance of the universe.

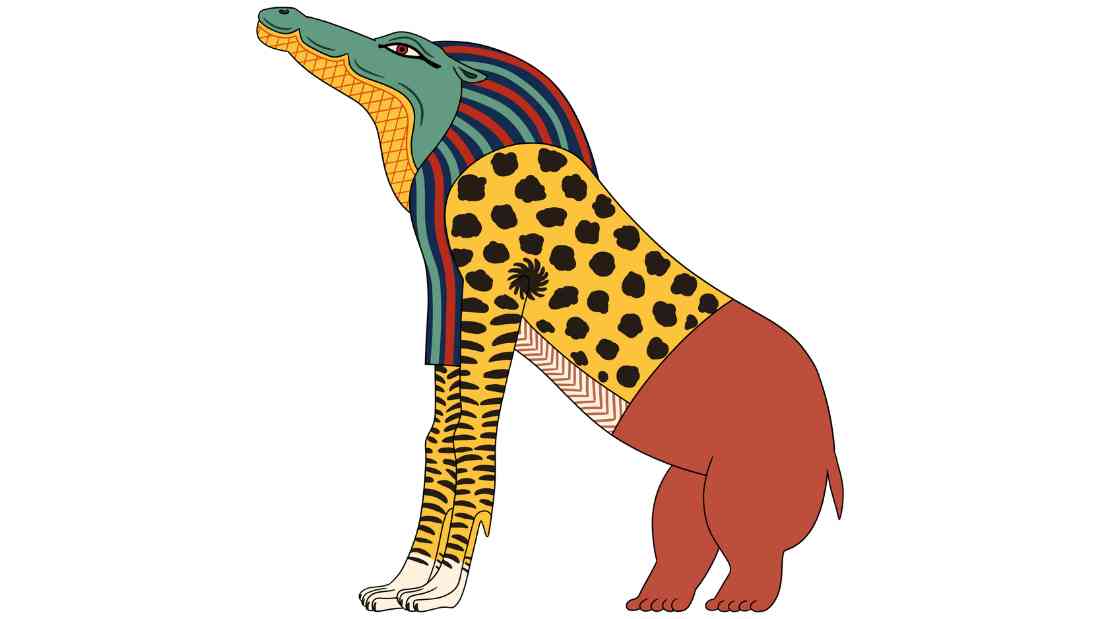

Ammit – The Devourer of Souls

Ammit, also known as Ammut, is a formidable figure in ancient Egyptian mythology.

Known as the “Devourer of Souls,” she is depicted as a composite creature with the head of a crocodile, the torso of a leopard, and the hindquarters of a hippopotamus.

Each aspect of her form symbolizes different elements of danger and power in the animal kingdom, reflecting her fearsome role in the afterlife.

In the Hall of Truth, the judgment place of the afterlife, Ammit sat beneath the scales of justice.

The deceased’s heart, considered the seat of the soul and moral character, was weighed against the feather of Ma’at, the goddess of truth and order.

If the heart was found to be heavier than the feather, indicating that the individual had led a life of sin, Ammit would devour it, resulting in the second death where the soul was denied the chance of an afterlife.

Ammit’s role was not that of a traditional goddess who was worshipped. Instead, she embodied the concept of divine retribution.

The fear of being devoured by Ammit encouraged moral behavior among the living, who aimed to lead virtuous lives to avoid such a fate. Her presence served as a deterrent for immoral actions and was a constant reminder of the consequences of one’s deeds in life.

Despite her terrifying image, Ammit played a crucial role in maintaining Ma’at, the fundamental order of the universe, by punishing those souls deemed unworthy by Osiris, the god of the dead and resurrection.

In this sense, she was not so much a malevolent entity as she was an enforcer of divine justice, integral to the ancient Egyptians’ understanding of morality and the afterlife.

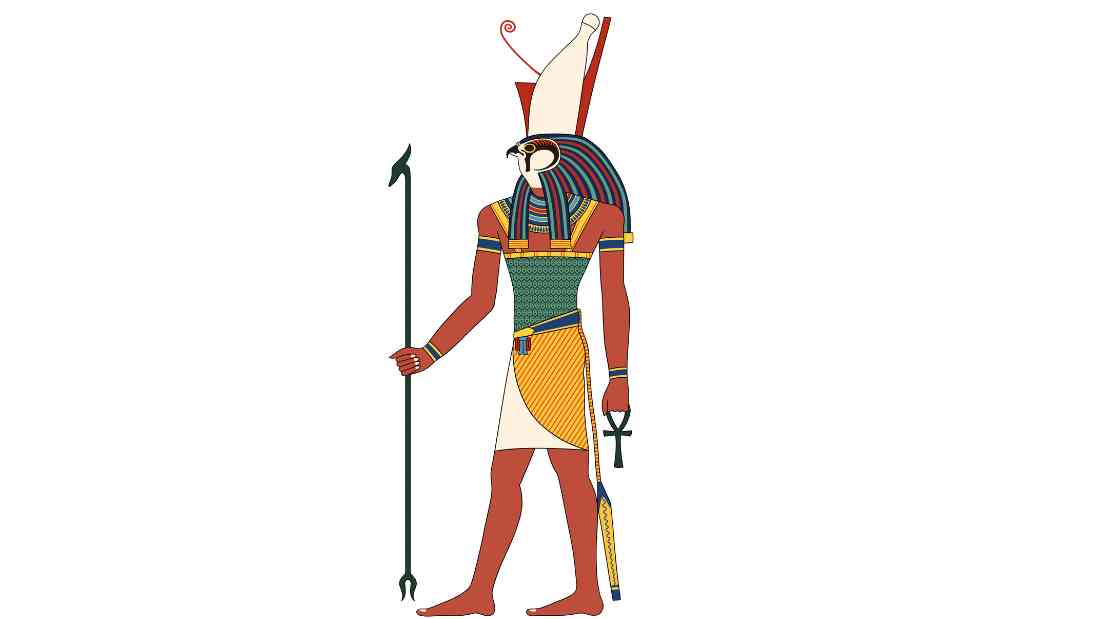

Horus – The Sky God

Horus, the falcon-headed deity who ruled the boundless skies, is a prominent figure within the pantheon of ancient Egyptian gods.

Epitomizing divine kingship and celestial power, Horus served as the protector of the pharaohs and a symbol of rightful rule.

As the son of Isis, the goddess of magic and healing, and Osiris, the god of the underworld, Horus’s lineage alone underscores his significance within the mythological narrative of ancient Egypt.

Often portrayed with the piercing eyes of a falcon, Horus was intrinsically linked to the sky.

His right eye was associated with the sun, representing the solar cycle’s vitality and unyielding energy. In contrast, his left eye was associated with the moon, symbolizing the lunar cycle’s tranquility and the soothing coolness of the night.

This dual symbolism reflected his dominion over both the day and night, underscoring his omnipresence in the celestial realms.

His connection to the sky was further emphasized by his name, which translates to ‘the distant one’ or ‘the one on high,’ reinforcing his status as the sovereign ruler of the heavens.

His far-reaching vision, signified by his falcon’s eyes, was believed to keep a watchful eye over the land, ensuring harmony and warding off chaos.

As the protector of the pharaohs, Horus was seen as the divine embodiment of the earthly kings.

The pharaohs were considered the ‘Living Horus,’ a testament to their divine right to rule. This association strengthened the legitimacy of the pharaohs’ reign, linking their authority directly to the gods.

The tale of Horus’s conflict with his uncle Set over the throne of Egypt forms a crucial part of his mythos. This epic battle, which ended in Horus’s victory, symbolized the triumph of order over chaos, further solidifying Horus’s role as a protector deity.

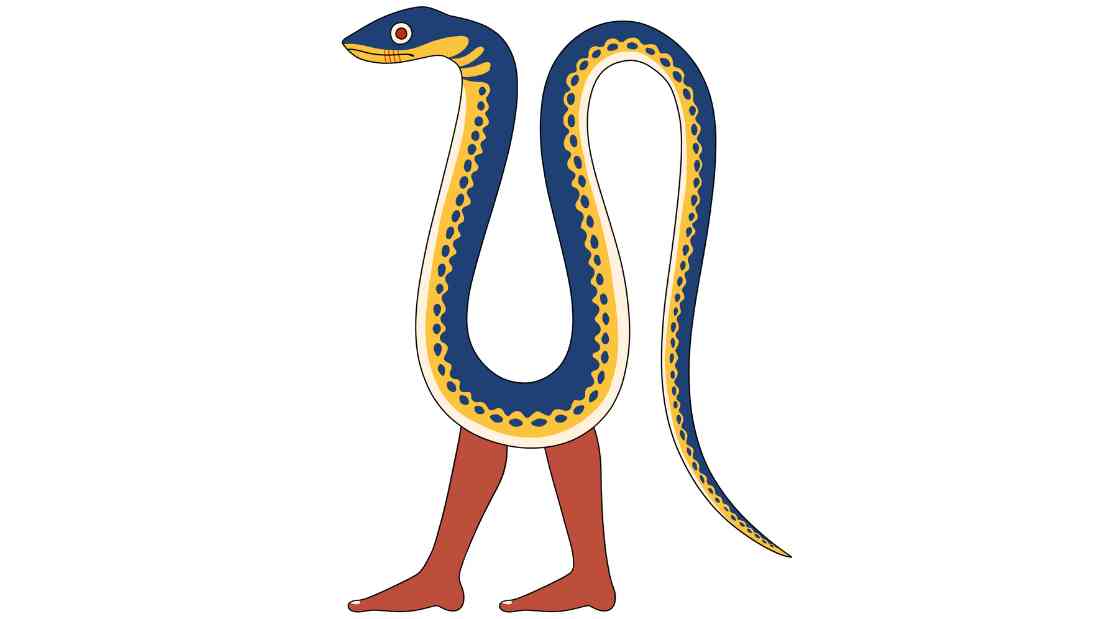

Nehebkau – The Protector of Souls

Nehebkau, also known as “He Who Unites the Ka,” is the protector god. His principal role was to join the ka, an aspect of the soul, to the body at birth and reunite it with the ba, another element of the soul, after death.

This crucial function places Nehebkau at the heart of the Egyptians’ understanding of life, death, and the transition between the two.

Nehebkau is often depicted as a serpent, a symbol associated with both protection and renewal in ancient Egyptian iconography. This depiction reflects his role as a protective deity and his involvement in the cycle of life and death.

Like Heka, the god of magic and medicine, Nehebkau is believed to have always existed, transcending the confines of time and space.

According the Egyptian mythology, he was present in the primordial waters that existed at the dawn of creation. He swam in these chaotic waters before Atum, the creator god, rose from the chaos to impose order.

This association positions Nehebkau at the very beginning of time, further emphasizing his timeless nature and his importance in the divine order of ancient Egyptian gods.

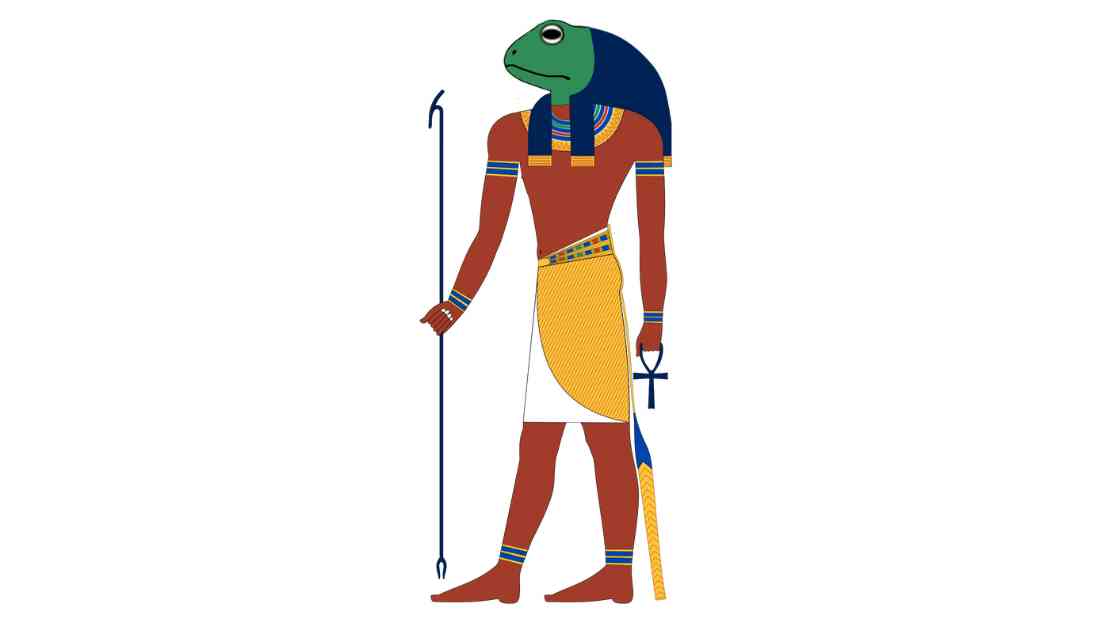

Heka – The God of Magic and Medicine

Heka, in ancient Egyptian mythology, is the god of magic and medicine, embodying the mysterious power that Egyptians believed permeated the universe.

His name itself means “activating the ka,” the aspect of the soul associated with life force. This gives insight into his role as a cosmic force that activates the vital energies within every living being.

Heka was considered a primordial deity who existed before the creation of the world. Unlike other gods who were born or created, Heka simply always was, underlining his fundamental role in the cosmos.

Heka is typically depicted as a man carrying a staff entwined with serpents, symbolizing his authority and connection to magical healing. Sometimes, he is shown with frog-headed attributes, reflecting his association with fertility and regeneration.

As the god of magic, Heka was the master of a force used by both gods and humans. This magic was not perceived as supernatural, but as a natural force that influenced everyday life. It was used for various purposes, from mundane tasks to grand rituals, and Heka was the source and ultimate controller of this power.

Heka’s association with medicine reflects the ancient Egyptians’ understanding of healing as a magical process. They believed that illnesses were caused by supernatural forces, and healing involved the use of spells, amulets, and potions to drive away these forces.

As the god of magic, Heka was naturally invoked in these healing practices, making him a protector of health.

Pakhet – The Lioness Hunting Goddess

Pakhet was revered as a hunting goddess who took the form of a lioness. Her name, translating to “She Who Scratches” or “Tearer,” aptly captures her fierce and relentless nature as a huntress.

As a consort of Horus, the sky god, Pakhet was integrated into the broader narrative of Egyptian cosmology. Her association with Horus underscored her status as a potent force in the pantheon of ancient Egyptian gods, highlighting her influence and importance.

Pakhet’s attributes were not confined to hunting alone but extended to embody elements of vengeance and justice.

She was associated with the vengeful aspects of Sekhmet, another lioness deity known for her wrath and destructive power. This connection reflected Pakhet’s formidable capabilities and her role as an avenger in the divine realm.

Simultaneously, Pakhet was linked to the justice of Isis, one of the most important goddesses in ancient Egypt. This association positioned Pakhet as a force of balance and fairness, balancing her aggressive hunting traits with a sense of righteousness and equity.

Believed to hunt at night and instill fear in her enemies, Pakhet was a symbol of the unseen threats that lurked in the darkness. Her nocturnal activities reflected the ancient Egyptians’ fear of the night and its hidden dangers, further amplifying her image as a powerful and terrifying deity.

Anubis – God of Embalming and the Dead

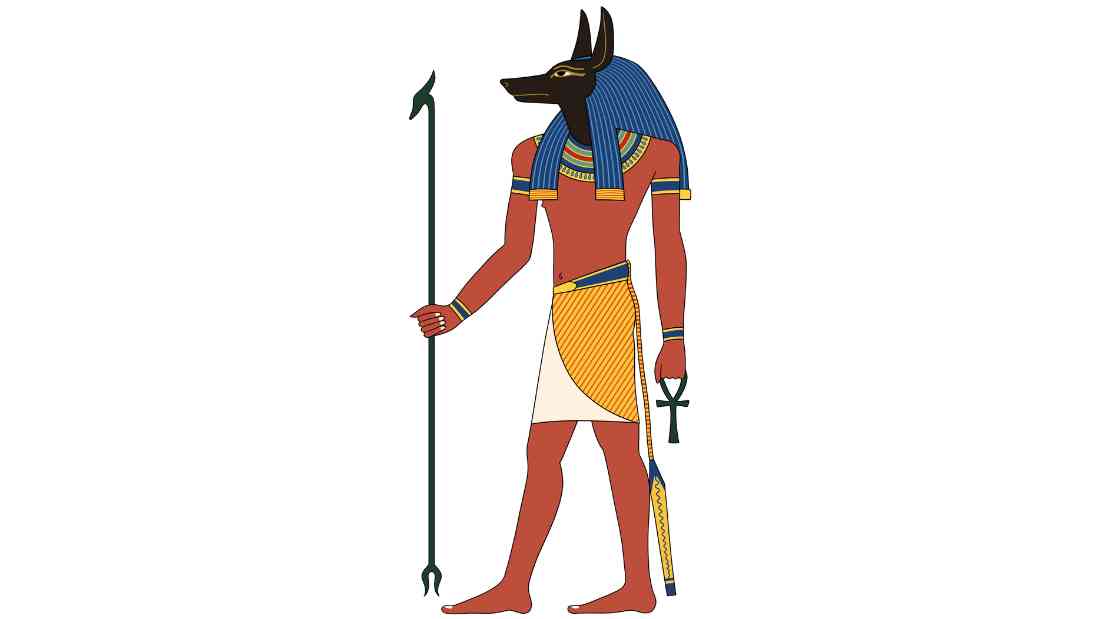

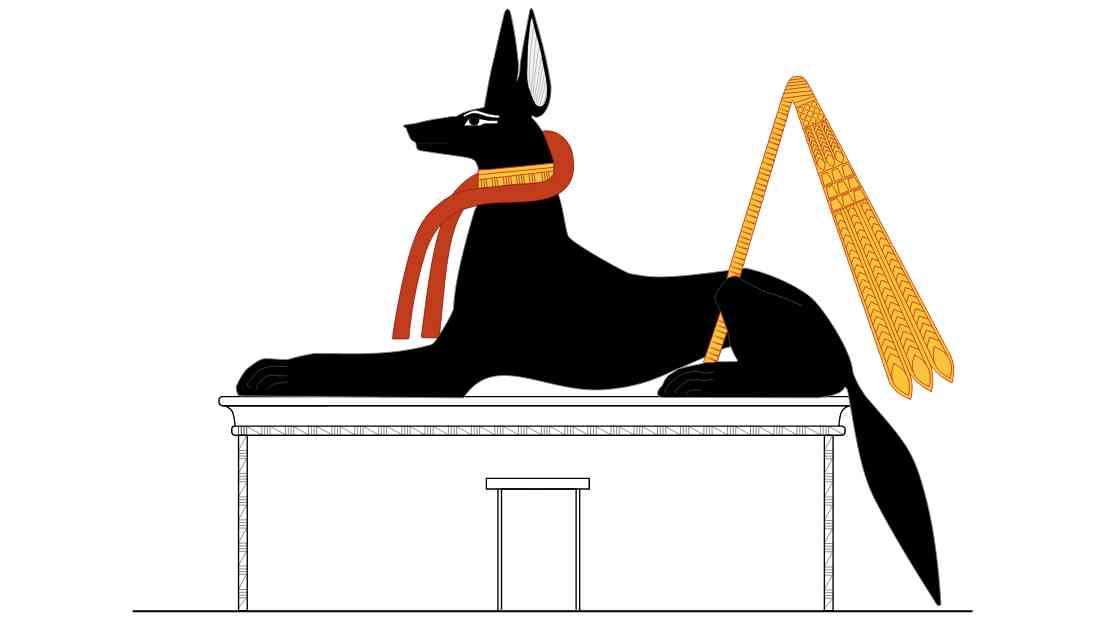

Anubis, the enigmatic god with a jackal’s head, holds a key position in the pantheon of ancient Egyptian gods.

As the god of embalming and the afterlife, Anubis was seen as the custodian of the dead, a guide for departed souls navigating the mysteries of the underworld.

Recognizable by his distinctive jackal head, Anubis’s iconography was inspired by the wild dogs or jackals often seen lurking at the edges of the desert, near the cemeteries.

This association with creatures that tread the line between life and death made Anubis a fitting symbol for the journey into the afterlife.

As the god of mummification, Anubis was believed to have embalmed the body of Osiris, thereby inventing the process of mummification.

He was thus the protector of the dead, ensuring their physical bodies were carefully preserved for their journey into the afterlife.

This role underscored the reverence ancient Egyptians had for the dead and the importance they placed on proper burial rites.

Beyond his embalming duties, Anubis also played a crucial role in the judgment of souls.

It was he who weighed the hearts of the deceased against the feather of Ma’at, the goddess of truth and justice.

This act, known as the ‘Weighing of the Heart,’ determined whether the soul would attain eternal life or be devoured by Ammit, the devourer of the dead.

As the overseer of this process, Anubis was seen as a fair and impartial judge, embodying the moral and ethical values central to ancient Egyptian culture.

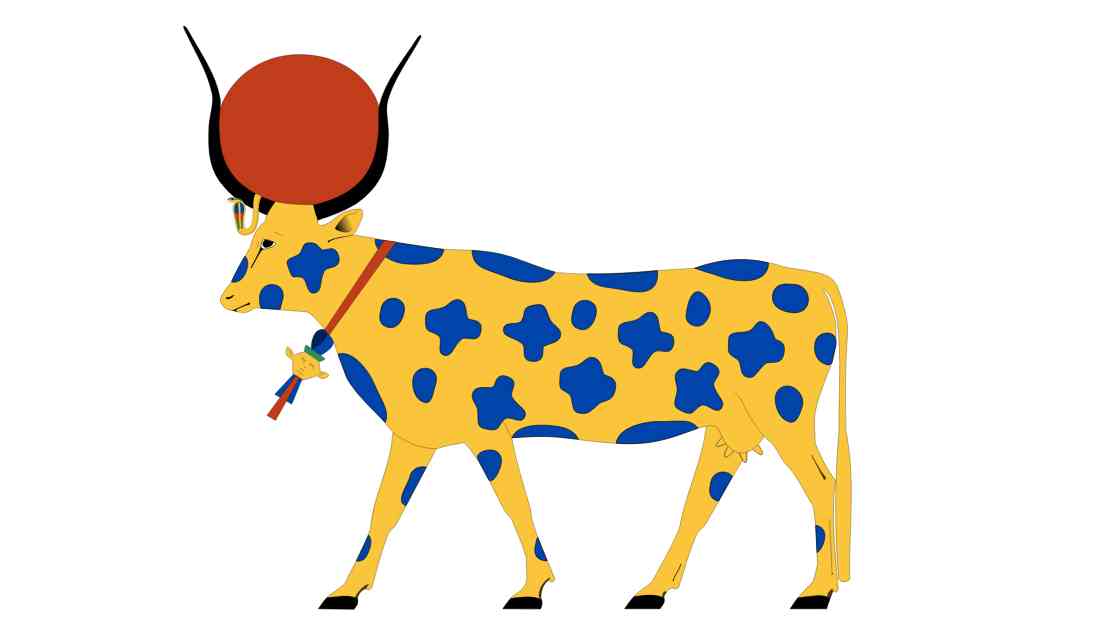

Mehet-Weret – The Celestial Cow Goddess

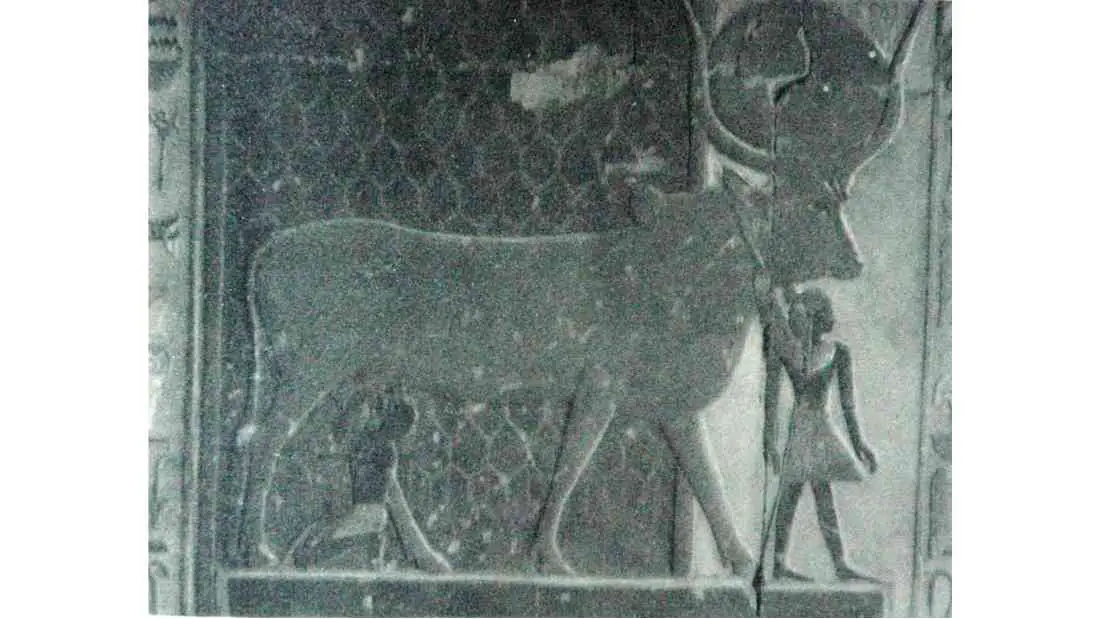

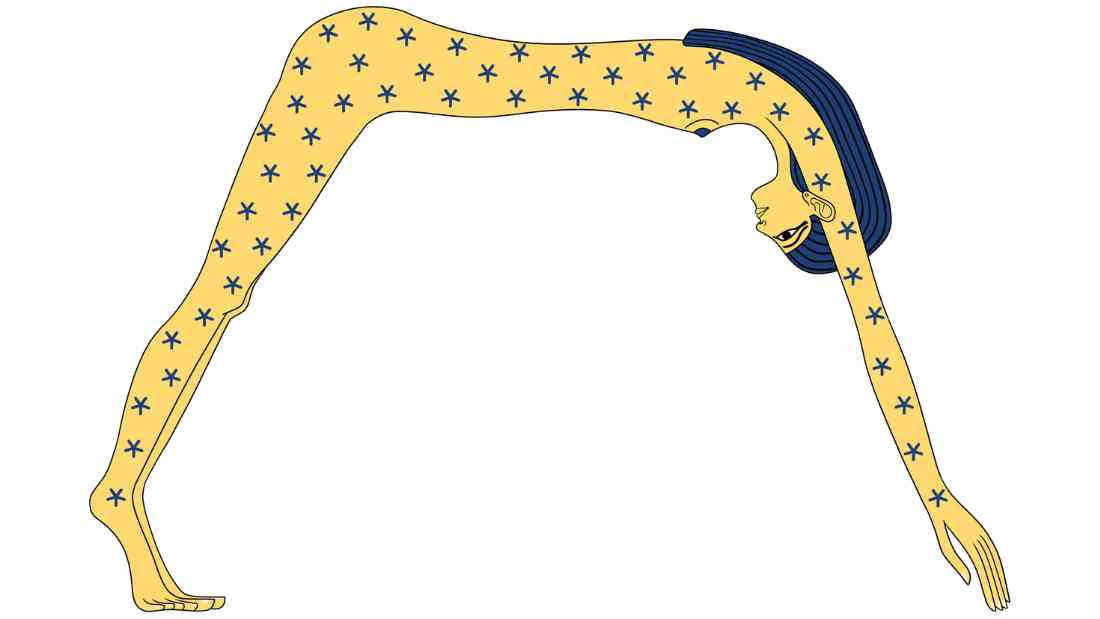

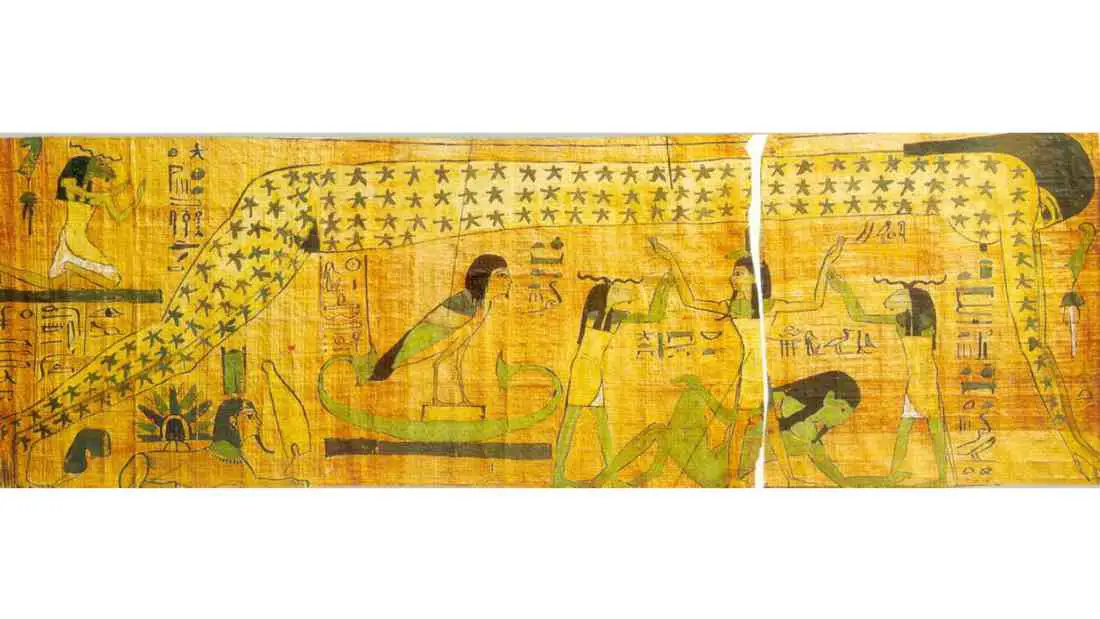

Mehet-Weret, one of the ancient Egyptian pantheon’s oldest and most revered gods, holds a special place in the mythology and cosmology of this ancient civilization.

Known as the celestial cow goddess, Mehet-Weret is a symbol of fertility, abundance, and creation. Her name, which translates to “Great Flood,” reflects her origins in the primordial waters of chaos.

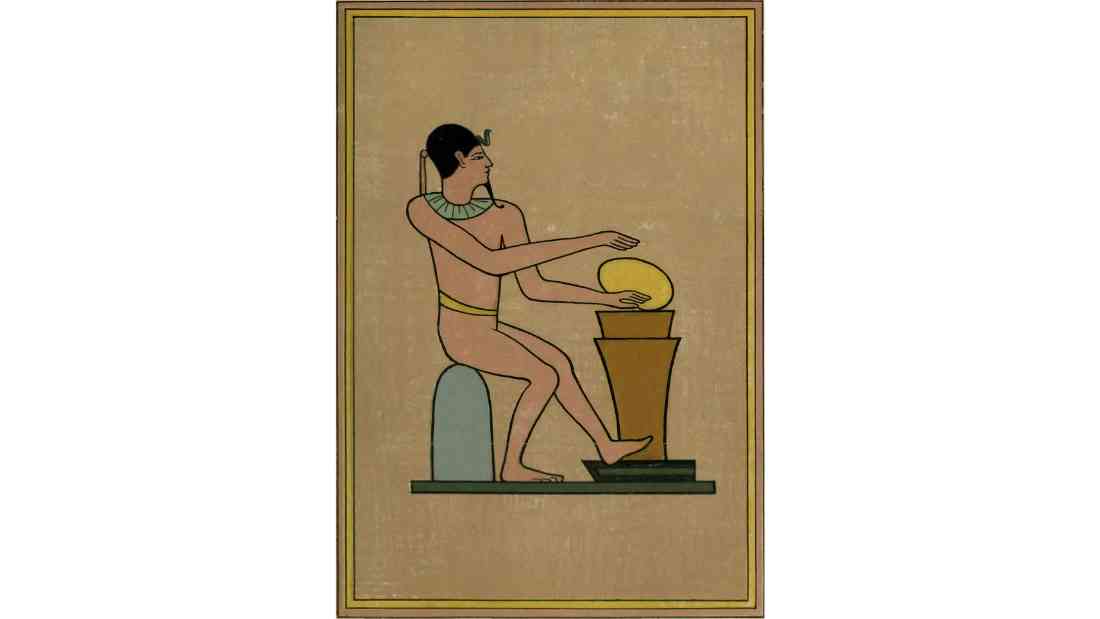

According to ancient Egyptian beliefs, Mehet-Weret emerged from these chaotic waters at the dawn of time, bringing forth the sun god Ra.

In an act that symbolizes the birth of light from darkness, she placed the newborn sun between her horns and lifted it into the sky each morning, marking the start of a new day.

This daily ritual was believed to renew the world, reinforcing Mehet-Weret’s role as a life-bringer and a sustainer of existence.

Over time, Mehet-Weret’s attributes were absorbed by Hathor, another prominent cow goddess in Egyptian mythology.

Hathor took over many of Mehet-Weret’s functions, including her association with the sky and her role as a mother figure to the sun god. Despite this, Mehet-Weret retained her distinct identity in the religious beliefs of the ancient Egyptians.

Hathor – Goddess of Love, Joy and Motherhood

Hathor is the daughter of Ra, the sun god, and in some narratives, she is the wife of Horus the Elder, another pivotal figure in the pantheon of ancient Egyptian gods.

Hathor was renowned for her diverse representations and wide-ranging influence.

Often depicted as a cow, Hathor embodies maternal attributes and celestial aspects, symbolizing fertility, love, beauty, and music.

Her most common form was that of a woman adorned with a headdress of cow horns cradling a sun disk. This imagery underscores her celestial aspect, linking her to the sun god Ra, and emphasizes her role in sky-related matters. Her association with the sun disk also portrays her as a solar deity, shedding light on her multifaceted nature.

However, Hathor’s depictions are not confined to bovine and human forms. She could also be represented as a lioness, showcasing her fierce and protective side, or a cobra, symbolizing her transformative and healing powers.

Furthermore, Hathor could take the form of a sycamore tree, an embodiment that underscores her nurturing qualities and links her to life and rejuvenation.

Hathor’s diverse representations reflect the multiple roles she played in the pantheon of ancient Egyptian gods. As a celestial and maternal figure, she was viewed as the mother of the pharaohs, providing them with divine legitimacy. As a lioness or a cobra, she was a protector and healer. And as a sycamore tree, she was a life-giver and nurturer.

Hathor also has an intriguing association with Sekhmet. Despite their starkly contrasting attributes, Hathor and Sekhmet are two sides of the same divine coin.

In one of the pivotal Egyptian myths, when Ra, the sun god, discovered a human conspiracy against him, he sent Hathor to punish the rebellious humans.

Hathor transformed into Sekhmet, the lioness goddess, to execute this task.

This transformation reveals the duality inherent in these deities, with Hathor representing life-giving aspects and Sekhmet embodying destructive power.

The association between Hathor and Sekhmet underscores the complex and multifaceted nature of divine beings in ancient Egyptian mythology, highlighting their capacity to embody opposing forces of creation and destruction.

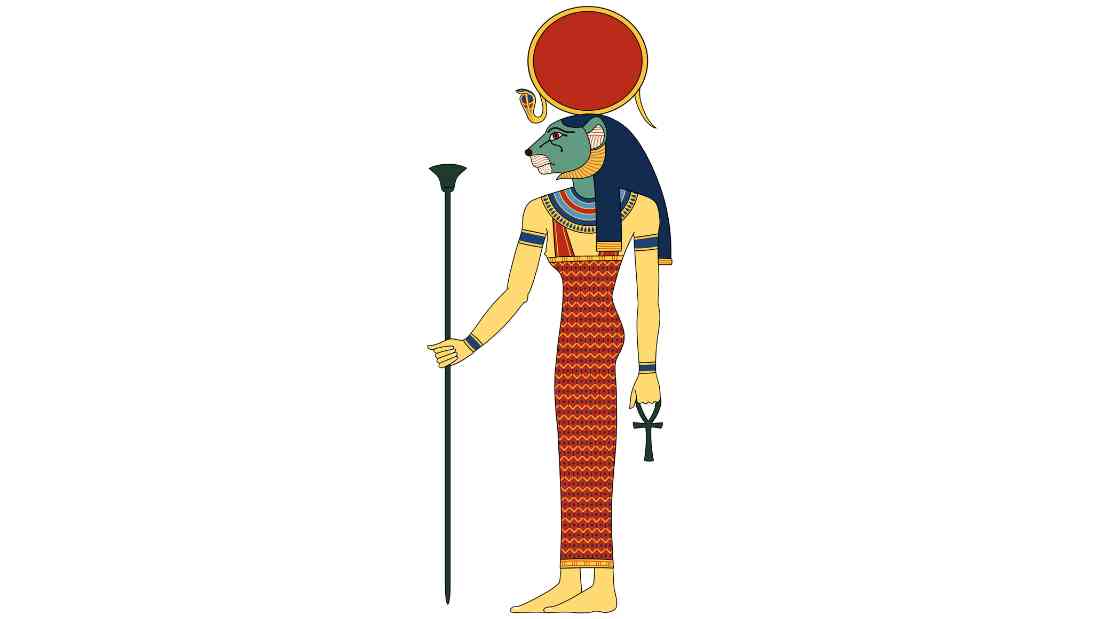

Sekhmet – The Vengeance of Ra

One of the most compelling narratives in ancient Egyptian mythology revolves around the end of Ra’s reign on Earth, involving the goddesses Hathor and Sekhmet.

As the story goes, Ra, the sun god and ruler of the Earth, discovered a human conspiracy against him. In response, he sent Hathor, who transformed into the formidable lioness goddess Sekhmet, to punish the rebellious mortals.

Sekhmet, living up to her reputation as “The Powerful One,” descended upon the Earth with unquenchable blood-lust.

Her wrath extended beyond the battlefield, resulting in a terrifying rampage that wreaked havoc across Egypt and threatened the annihilation of humanity.

The ferocity of Sekhmet’s assault was so immense that it almost led to the extinction of mankind.

To avert this catastrophe, Ra and the other gods hatched an ingenious plan. They created a vast lake of beer and dyed it with red ochre, giving it the appearance of a sea of blood.

Consumed by her blood-lust, Sekhmet mistook the beer for blood and drank the entire lake.The effects were immediate and dramatic.

Overwhelmed by the intoxicating brew, Sekhmet’s fury subsided, and she became so inebriated that she abandoned her destructive spree.

With her thirst for blood quenched by the deceptive beverage, Sekhmet returned peacefully to Ra, marking the end of her rampage and saving humanity from total destruction.

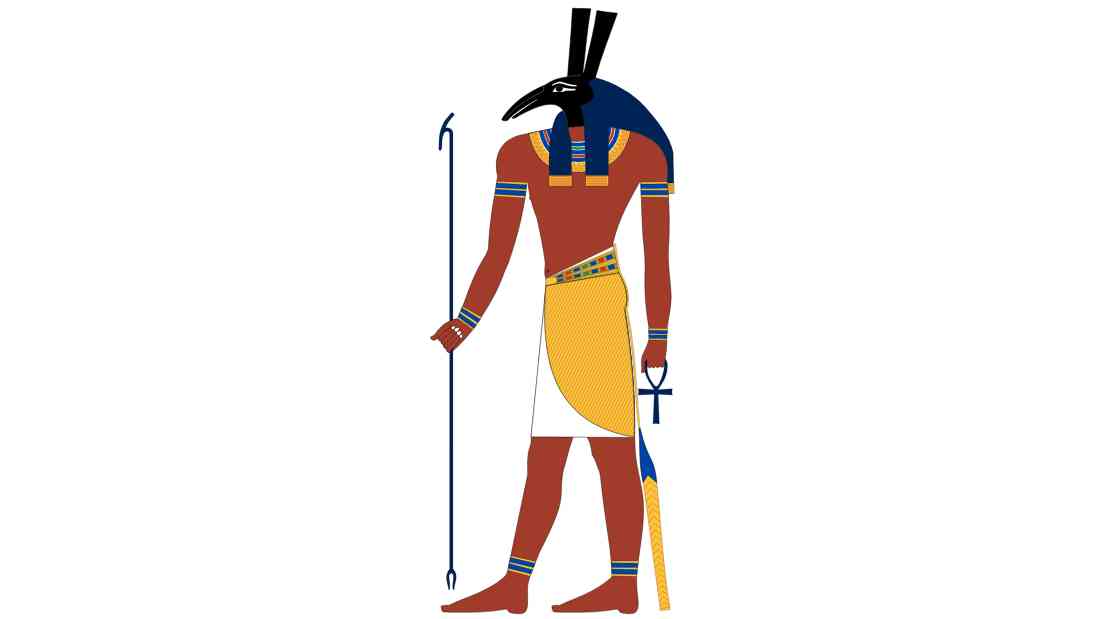

Set – God of Chaos and Storms

Set is a complex and intriguing figure within the pantheon of ancient Egyptian gods.

As the god of chaos, storms, and war, Set embodies the unpredictable and tumultuous forces of nature and life.

His character, often associated with disruption and conflict, commands both fear and reverence for his potent power and volatile nature.

Unlike other deities in ancient Egyptian mythology who are represented by recognizable animals, Set is portrayed with an enigmatic creature’s head, often referred to as the ‘Set animal.’

This creature, bearing a curved snout and tall, squared-off ears, is unlike any known species, reinforcing Set’s association with the unfamiliar and chaotic.

As the god of chaos, Set symbolizes the unpredictable and potentially destructive aspects of existence.

He is often depicted as the antagonist in various mythological narratives, representing the forces that disrupt order and harmony. Yet, this association with chaos is not entirely negative – it also underscores the necessity of change and transformation, elements that are integral to the cycle of life.

Set’s dominion extends over storms, embodying the raw and untamed power of nature.

In a land like Egypt, where the climate is typically dry, storms can be both destructive and life-giving – bringing much-needed rain but also potentially devastating floods. This duality reflects Set’s character, a god who can bring both harm and benefit.

Moreover, as the god of war, Set was revered for his fierce strength and strategic prowess. He was often invoked for protection in battle, underscoring his role as a powerful defender despite his links to chaos and conflict.

Despite his complex and often negative associations, Set held a significant place of respect among the ancient Egyptian gods. His unpredictability and power were seen as necessary counterpoints to the order represented by other deities.

Astarte – Phoenician Goddess of Fertility and Sexuality

Astarte is a goddess of paramount importance in ancient Phoenician mythology, celebrated for her domains of fertility and sexuality.

She is often closely equated with other prominent goddesses from different cultures, including Aphrodite of the Greeks, Inanna/Ishtar of Mesopotamia, and Sauska of the Hittites.

In Egyptian mythology, Astarte is presented as a consort to Set, the god of desert, storms, disorder and violence, hinting at a complex interplay of forces, balancing Set’s destructive tendencies with Astarte’s life-giving powers.

The coupling is facilitated by the goddess Neith, who gives Astarte and another goddess, Anat, to Set as consorts.

Astarte’s title, “Queen of Heaven,” underscores her elevated status within the divine hierarchy of ancient Egyptian gods. This epithet also suggests her association with celestial bodies, particularly the moon and Venus, often symbolizing femininity and fertility.

Thoth – The Enlightened God of Wisdom, Writing, and Knowledge

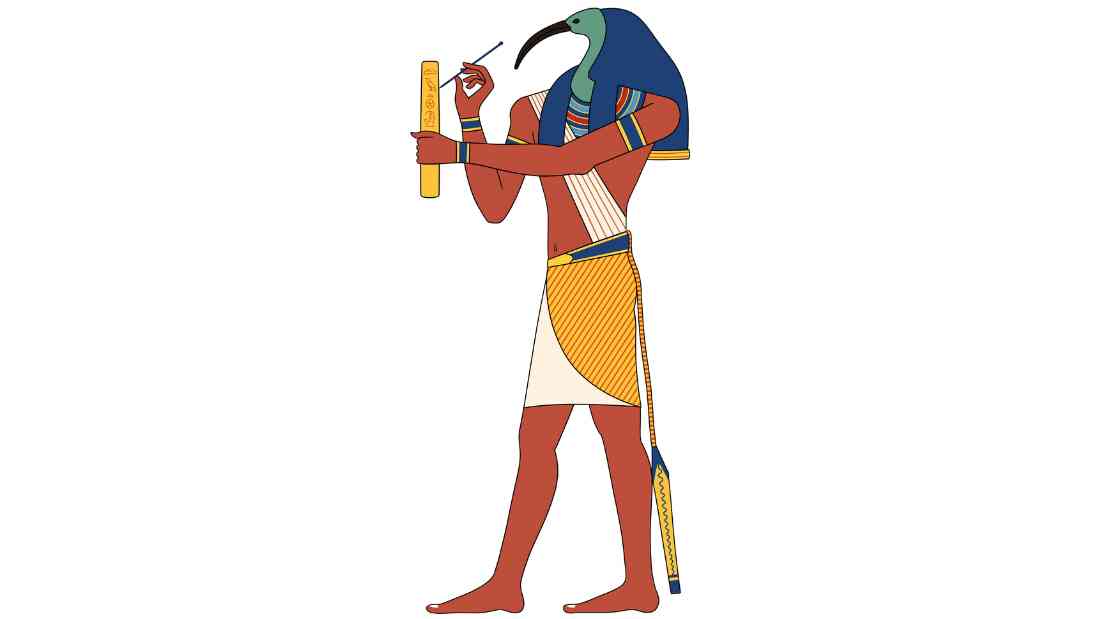

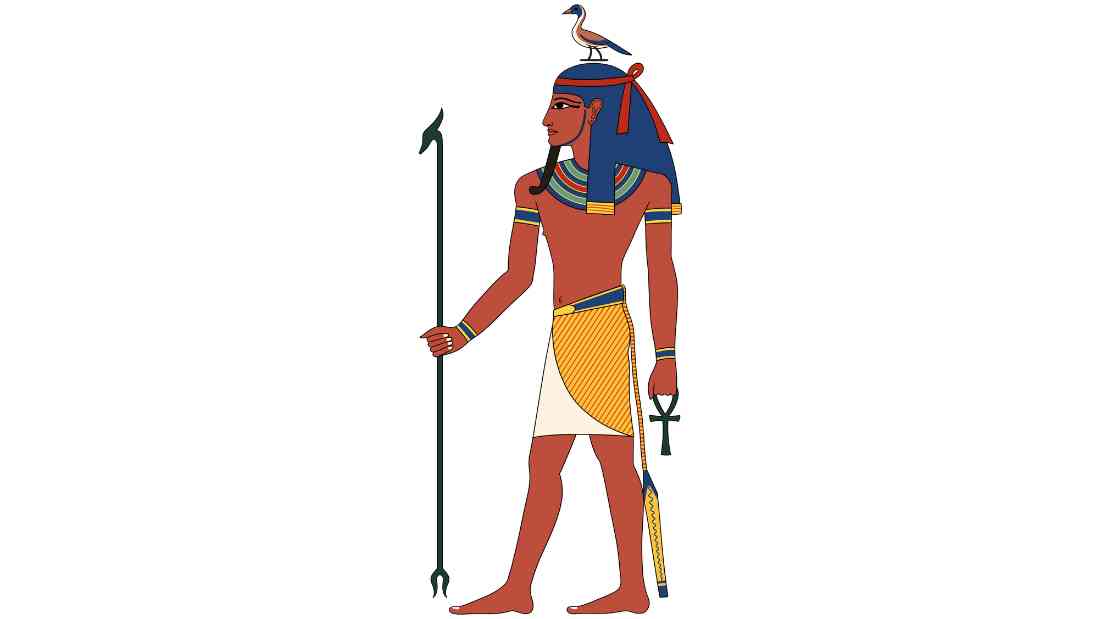

Thoth, known for his distinctive ibis-headed depiction, holds a crucial place in the pantheon of ancient Egyptian gods.

As the patron of scribes and wisdom, he is a symbol of intellectual pursuits, knowledge, and judgment. He is credited with the invention of hieroglyphics, the sacred writing system of ancient Egypt, further underscoring his association with wisdom and learning.

Thoth’s iconography as an ibis or a baboon underlines his association with wisdom.

Both animals were considered wise in ancient Egyptian culture, making them fitting symbols for Thoth’s role as the god of wisdom. The ibis, in particular, was seen as a careful and meticulous creature, mirroring the precision and attention to detail required in writing and scholarly work.

Thoth is credited with the invention of hieroglyphics, thereby establishing the foundation of ancient Egyptian written communication. As the inventor of writing, he was the protector of scribes, who played a critical role in administrative, religious, and scholarly activities.

Beyond his association with writing, Thoth was also the god of wisdom. He was believed to possess comprehensive knowledge of all things in the universe, including the secrets of the Egyptian gods and the mysteries of creation. His wisdom extended to the realms of law and justice, and he was often invoked in situations requiring discernment and judgment.

Moreover, Thoth was also associated with the measurement and marking of time. He was considered the keeper of divine records, tracking the passage of time and the unfolding of events. This role further emphasizes his association with knowledge and the orderly functioning of the world.

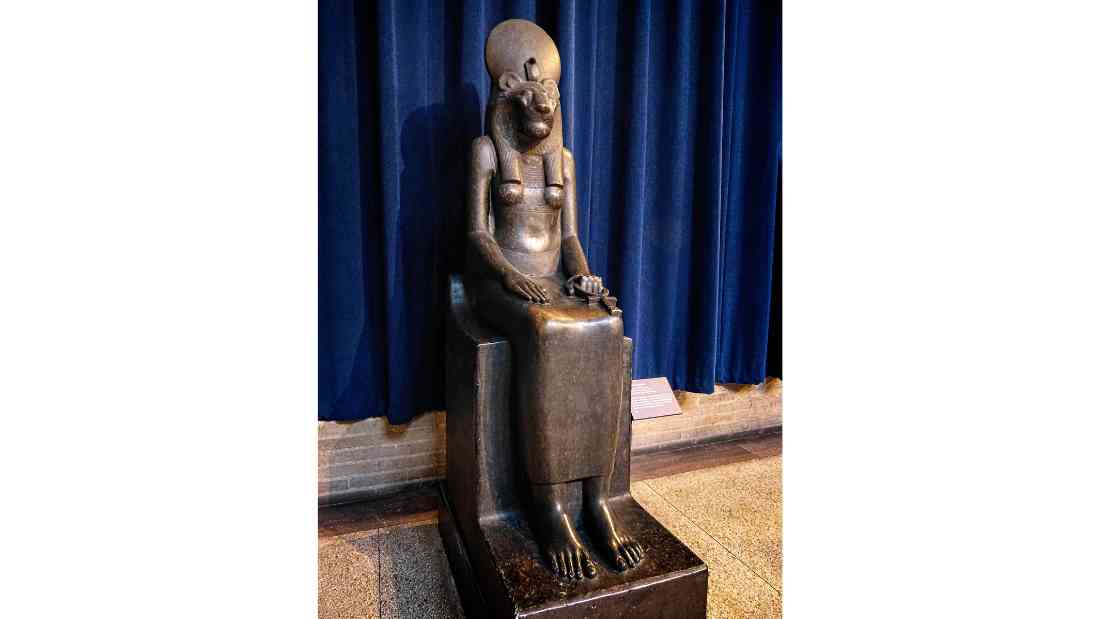

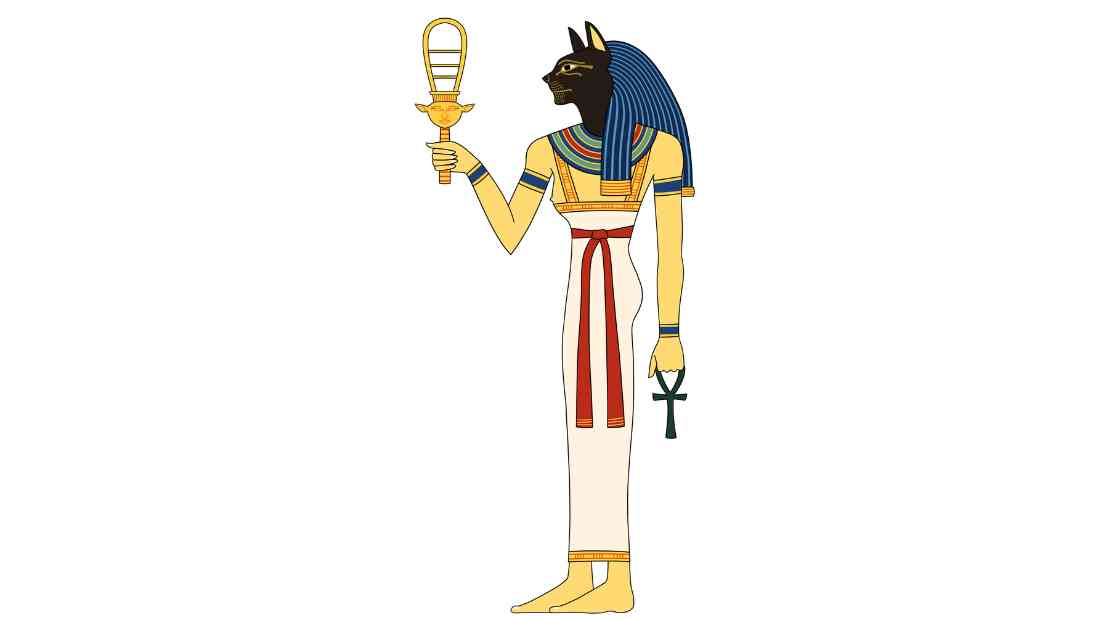

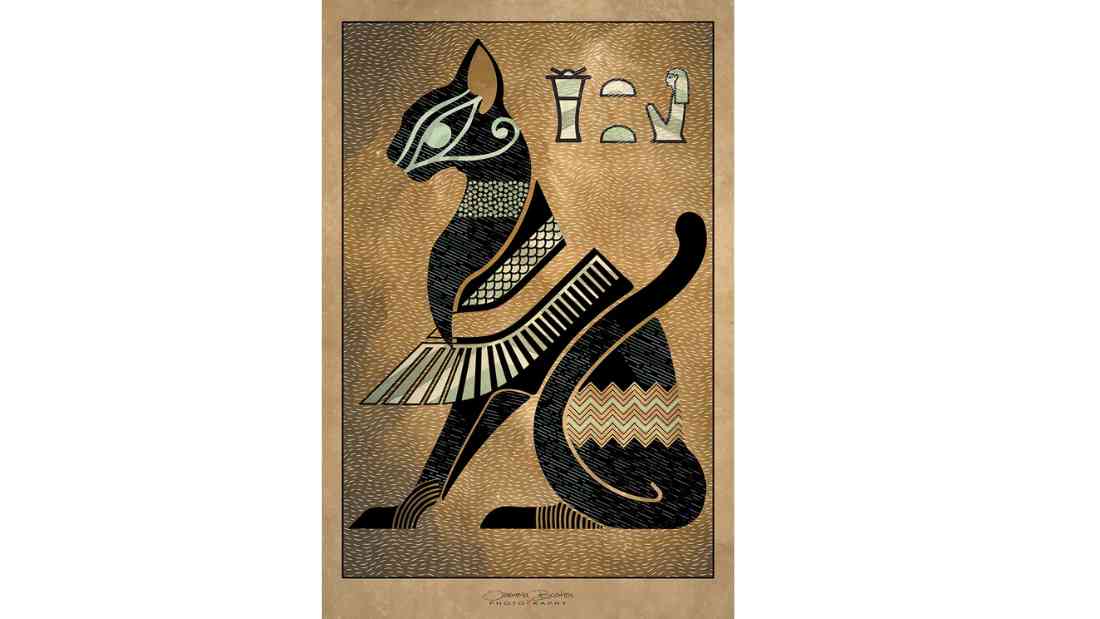

Bastet – The Lioness Goddess of Ancient Egypt

Bastet, also known as Bast, holds a significant place in ancient Egyptian mythology as the goddess of home, fertility, and childbirth, protector of the pharaoh, and defender of the sun god, Ra.

The name Bastet means “She of the Ointment Jar,” which reflects her association with protection and blessings.

Initially depicted as a lioness warrior, Bastet represented the fierce, protective qualities of a mother. As the civilization progressed, her image softened to that of a domestic cat, symbolizing the nurturing aspects of motherhood.

Often portrayed as a lioness or a woman with the head of a lioness or domestic cat, Bastet was a symbol of grace and poise. She wore a gold necklace and carried a sistrum, an ancient musical instrument, signifying her connection with music and dance.

Bastet was also associated with the Eye of Ra, a powerful protective deity. As the daughter of Ra, she played a crucial role in ancient Egyptian religion, defending Ra from his enemies and ensuring the sun’s daily journey across the sky.

Her role as a protector extended to the domestic sphere as well. Ancient Egyptians believed that Bastet watched over homes and pregnant women, safeguarding them from evil spirits and disease.

Moreover, Bastet was the presiding deity of the city of Bubastis, where grand festivals were held in her honor. These celebrations were renowned for their joyous dancing, music, and feasting, further emphasizing her reputation as a goddess of pleasure and festivity.

Anat – The Canaanite Goddess of Fertility, Sexuality, Love, and War

Anat, a powerful and complex figure in ancient mythology, embodies an intriguing blend of attributes. As a goddess of fertility, sexuality, love, and war, she holds a unique position among the ancient Egyptian gods.

Her origins are believed to lie in Syria or Canaan, but her influence extended far beyond these regions, permeating various ancient cultures and societies.

Anat’s image is multifaceted and somewhat paradoxical.

In some historical texts, she is ascribed the title ‘Mother of the Gods’, indicating a role of supreme maternity and nurturing. This aspect aligns with her association with fertility and highlights her importance in the creation and sustenance of life.

In contrast, other sources depict Anat as a virgin, untouched and independent. This depiction might seem at odds with her role as a fertility goddess, but it could also symbolize purity and the concept of self-contained potency.

Moreover, Anat’s sensuality and eroticism are also key characteristics. Described as the most beautiful of the goddesses, she embodies the allure and power of feminine beauty.

She is often depicted as a desirable figure, radiating a captivating charm that transcends physicality.

However, Anat is not merely a figure of love and beauty. She is also a formidable warrior goddess, known for her fierce and indomitable spirit. This martial aspect of Anat underscores her strength and resilience, portraying her as a protector and a force to be reckoned with.

Thus, Anat’s persona encapsulates the full spectrum of life – from creation and love to protection and conflict.

Anti – The Hawk God of Upper Egypt and His Association with Anat

Anti is a lesser-known but significant deity in the pantheon of ancient Egyptian gods.

Associated with the hawk, a bird that holds great symbolic value in Egyptian culture, Anti is primarily worshipped in Upper Egypt.

The hawk is a symbol of the sky, the sun, and the divine in Egyptian mythology, reflecting the god’s high status. It is seen as a protective figure, a guardian of the pharaoh and the Egyptian people.

Anti, as the Hawk God, embodies these qualities, representing protection, vigilance, and strength.

Interestingly, Anti has connections with the Canaanite goddess Anat. This association stems from cultural exchanges between ancient Egypt and Canaan, which influenced their respective mythologies.

Anti and Anat were sometimes merged into a single deity in some contexts, combining their attributes and roles, presenting an intriguing blend of Egyptian and Canaanite mythologies.

This amalgamation of the two deities resulted in a complex figure embodying both nurturing and protective qualities – a testament to the fluidity and interconnectedness of Egyptian mythology.

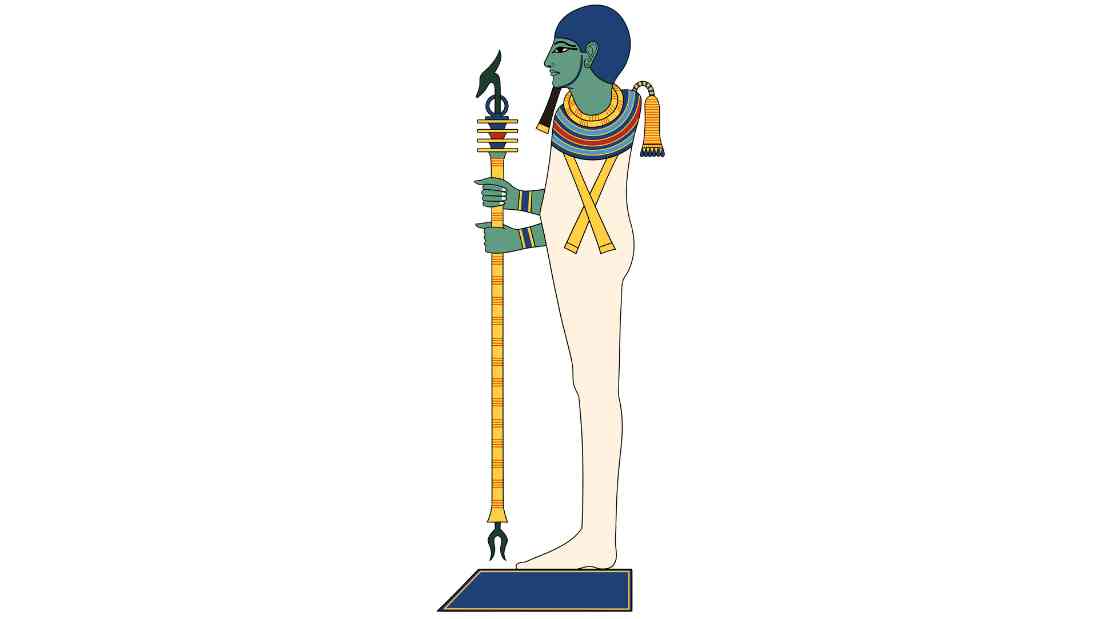

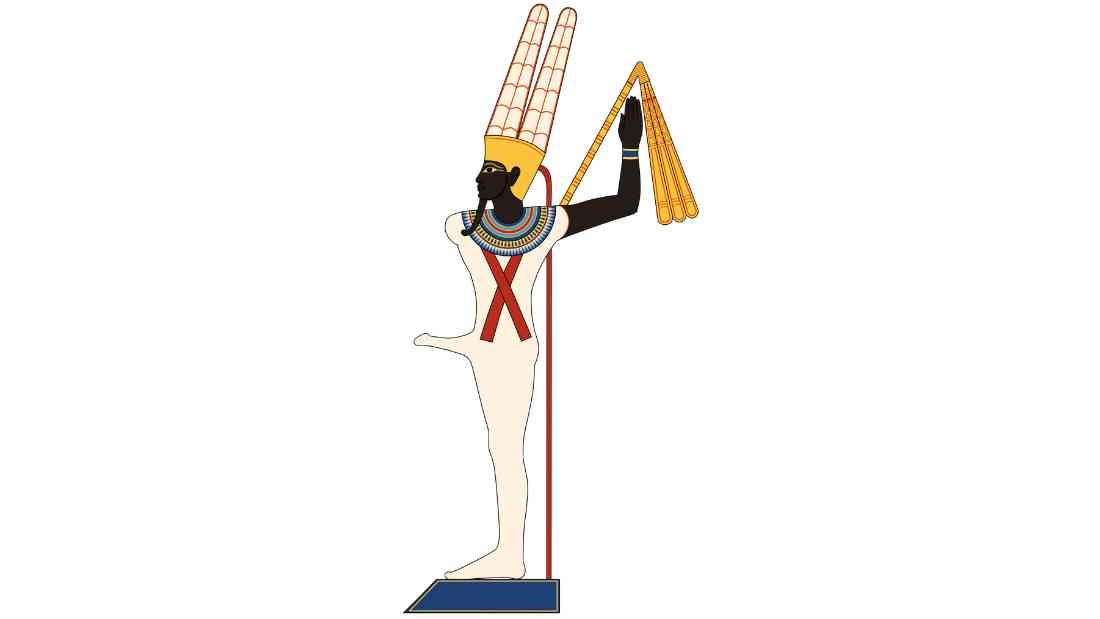

Ptah – The Creative God of Ancient Egypt

Ptah, one of the oldest and most significant deities in ancient Egyptian mythology, is revered as the god of craftsmen, architects, and builders. He is also recognized as the divine patron of the arts, metalworking, and sculpture.

The name Ptah means “the opener,” a title that signifies his role as a creative force.

According to ancient Egyptian cosmology, Ptah is the creator god who brought the universe into existence through his heart’s thoughts and his tongue’s command. This belief underscores the importance of words and thought in the act of creation, a concept deeply ingrained in ancient Egyptian culture.

Ptah is often depicted as a mummified man wearing a skull cap, holding a staff that combines the ‘ankh‘ symbol (representing life), the ‘djed’ pillar (symbolizing stability), and the ‘was’ scepter (denoting power and dominion). This imagery not only symbolizes his creative power but also his authority over life and stability.

As the god of craftsmen and builders, Ptah was highly respected by laborers and artisans. His wisdom and skill were believed to inspire and guide them in their work.

Temples dedicated to Ptah, such as the great temple in Memphis, his cult center, became important centers for arts and crafts.

Moreover, Ptah also played a significant role in the afterlife. He was considered the god who reshapes bodies and souls in the underworld, preparing them for their eternal journey.

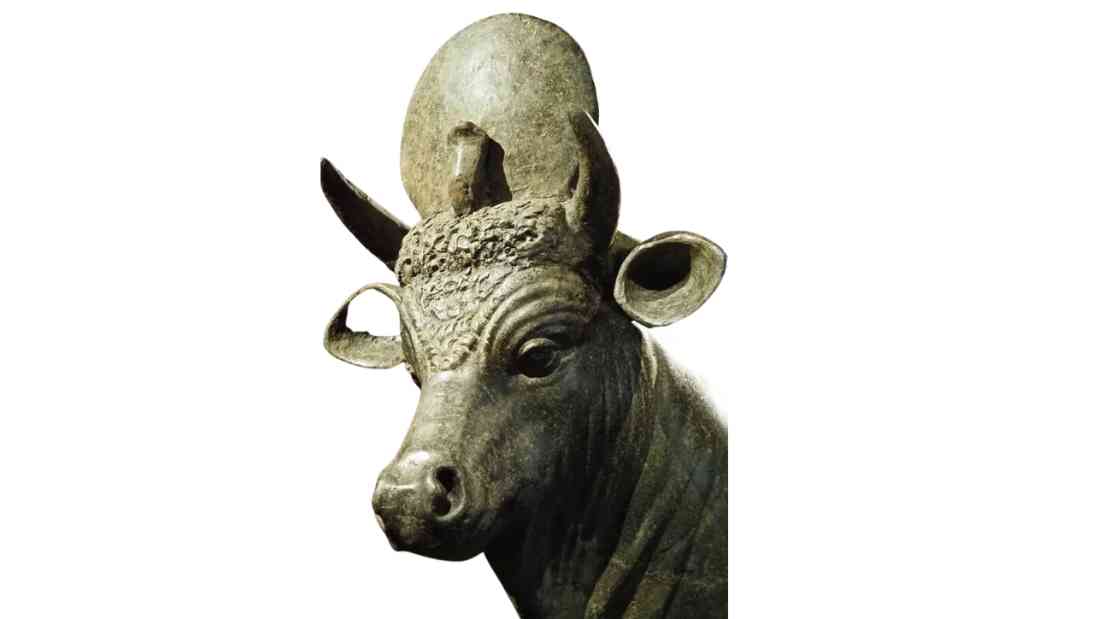

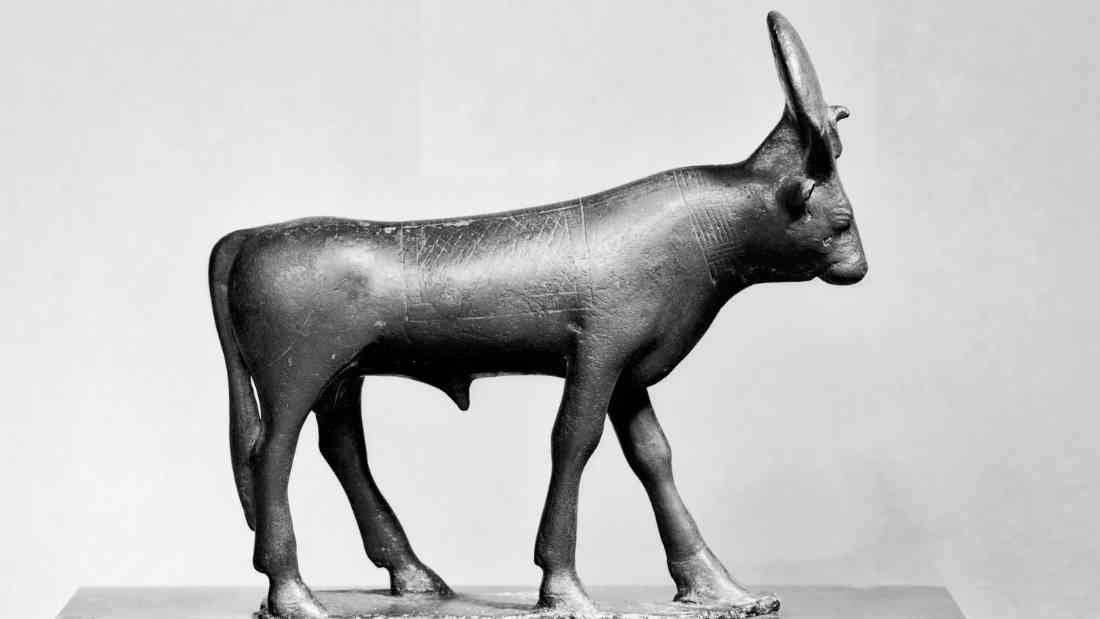

Apis – The Divine Bull and Incarnation of Ptah

Revered as an incarnation of the god Ptah, the creator deity and patron of craftsmen, Apis, the divine bull, symbolizes fertility, strength, and rebirth.

His worship was centered in Memphis, one of the oldest and most important cities in ancient Egypt.

Apis is one of the earliest gods of ancient Egypt, with depictions dating back to around 3150 BCE on the Narmer Palette, a significant archaeological artifact from the Early Dynastic Period.

This early representation underscores the god’s enduring relevance in the evolving pantheon of Egyptian deities.

The Apis cult, dedicated to the worship of the divine bull, was one of the most significant and long-lived in the history of Egyptian culture. The longevity of this cult attests to the deep-seated reverence for Apis and his associated deity, Ptah.

The cult’s rituals often involved the ceremonial care and eventual mummification of selected bulls believed to be manifestations of Apis.

In the grand scheme of Egyptian mythology, Apis served as a powerful intermediary between humans and the gods.

As an earthly incarnation of Ptah, he provided a tangible link to the divine, allowing people to interact directly with a god’s presence. This interaction took the form of offerings and rituals aimed at seeking the gods’ favor or understanding their will.

Furthermore, Apis’s association with fertility and rebirth connected him with the cycles of nature and life, reinforcing the ancient Egyptians’ belief in the cyclical nature of existence and the promise of renewal.

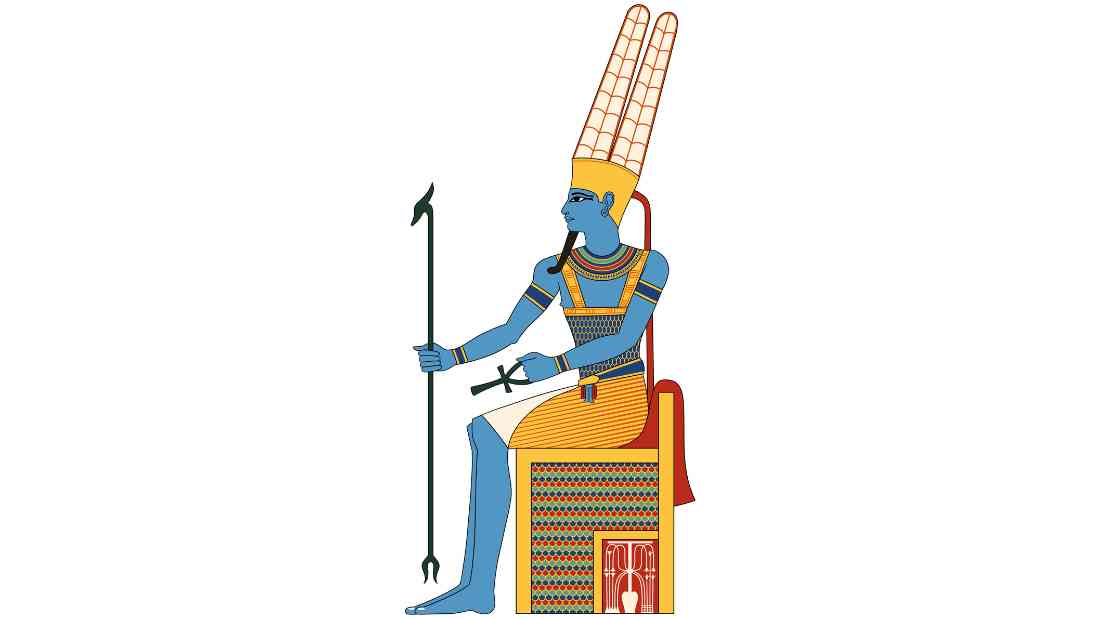

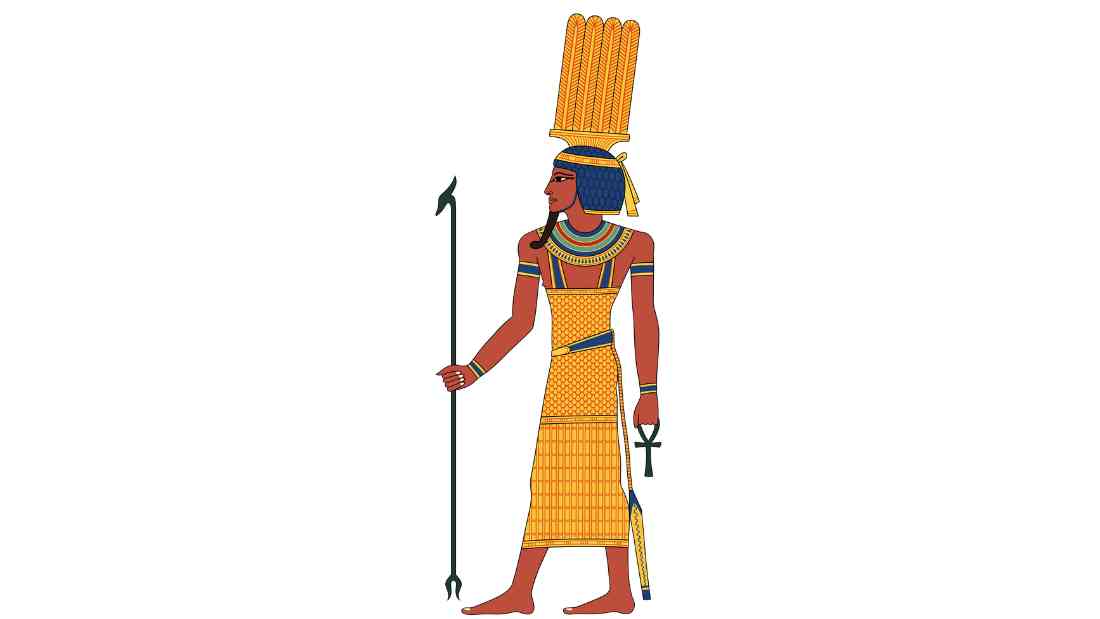

Amun (Amun-Ra) – The God of the Sun and Air

Amun, also known as Amun-Ra, is one of the most powerful and popular deities in Egyptian mythology.

As the god of the sun and air, he held a central role in the pantheon of ancient Egyptian gods and was revered for his omnipotence and mystery.

Amun’s influence was so profound that he was often merged with Ra, the ancient Egyptian sun god, to form Amun-Ra.

This combined deity represented the essential life-giving forces of the sun and air, embodying the creative powers necessary for all life.

As Amun-Ra, he was depicted as a man with a ram head or a man wearing a crown with sun disk and two tall plumes, symbols of his authority and power.

Amun was the patron god of Thebes, one of the most important cities in ancient Egypt.

Here, he was worshipped as part of the Theban Triad, which included Amun, his consort Mut, the goddess of motherhood, and their son Khonsu, the moon god.

Together, this divine family played a significant role in the religious life of Thebes, with grand temples built in their honor, the most famous being the Karnak temple complex.

The worship of Amun reached its zenith during the New Kingdom period of ancient Egypt, where he was hailed as the ‘King of the Gods’. His popularity even extended beyond Egypt, with his worship spreading to other parts of Africa and the Mediterranean.

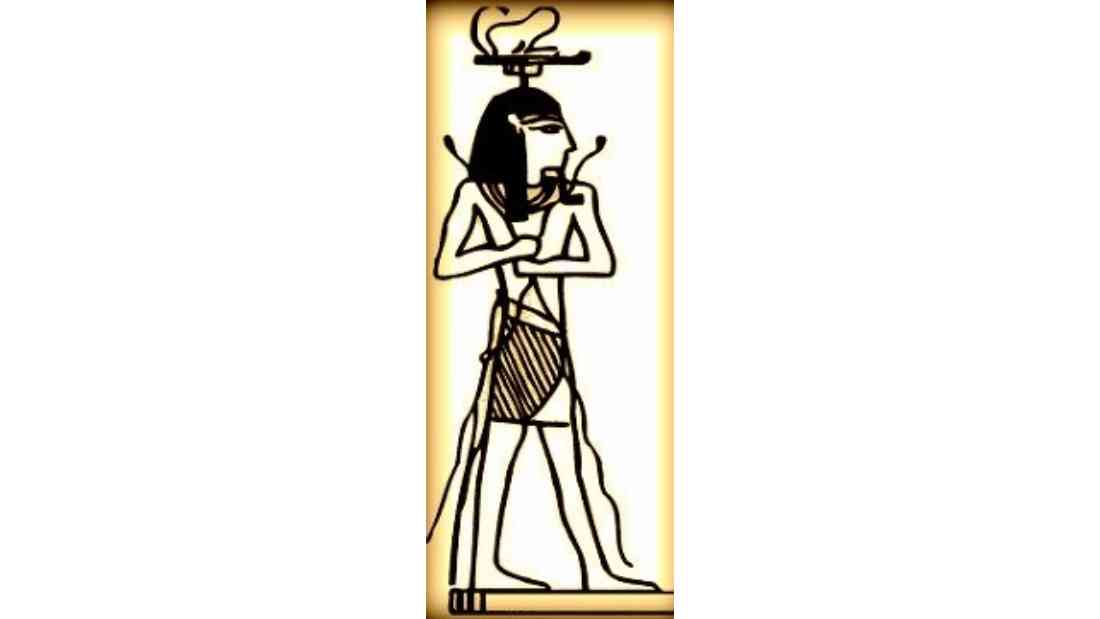

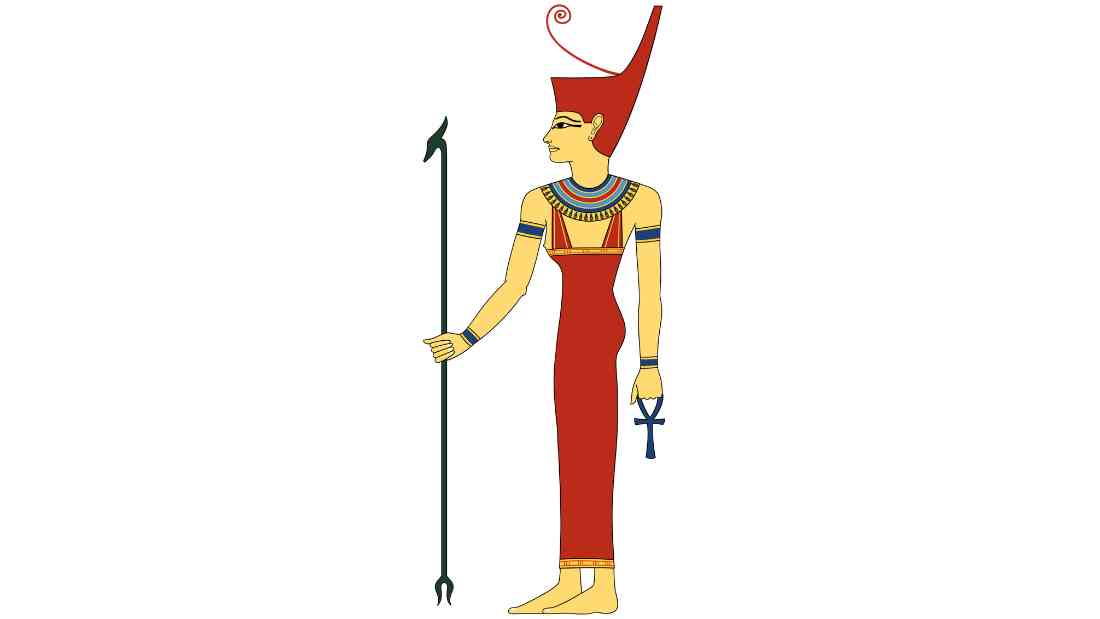

Amunet – The Goddess of Hidden and Unseen Forces

Amaunet, a deity in the Hermopolitan Ogdoad of ancient Egyptian religion, represents the hidden and unseen forces in the universe.

As part of the Ogdoad—a group of eight primordial deities—Amaunet and her male counterpart, Amun, symbolize the concept of the hidden or the invisible.

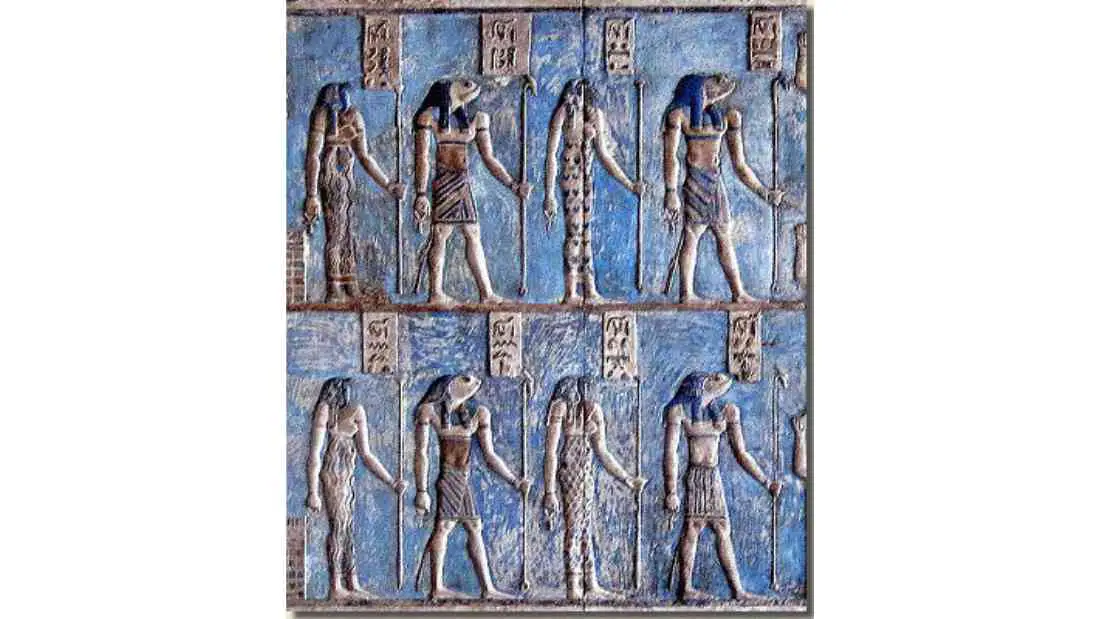

Eternal Space, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The name Amaunet translates to “the female hidden one,” reflecting her role as the embodiment of the unseen powers and mysteries of life. This goddess is particularly associated with the primordial waters of Nun, from which the world was believed to have emerged.

Amaunet is often depicted as a woman wearing the Red Crown, a symbol of Lower Egypt.

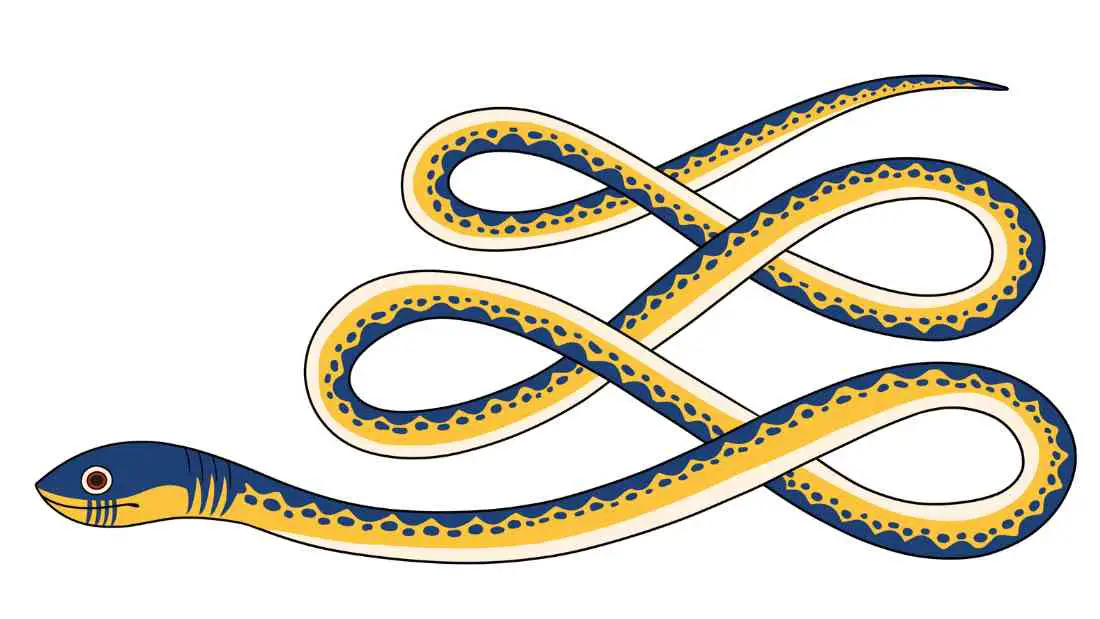

Other depictions represent her in an anthropomorphic form with the head of a snake, which aligns her with the other female deities of the Ogdoad who are also portrayed with serpentine features.

This snake symbolism, often associated with renewal, might be interpreted as a nod towards Amaunet’s association with the mysterious forces of creation and rebirth.

Despite her abstract realm, Amaunet holds a significant place in ancient Egyptian cosmology. Her representation of the hidden forces complements the other deities of the Ogdoad, who together embody the conditions from which the ordered world arose.

Her unseen forces are considered fundamental to the process of creation, making Amaunet integral to the ancient Egyptian understanding of the universe’s origins.

Mut – The Mother Goddess

Mut is an emblematic figure in ancient Egyptian mythology, known for her role as a mother goddess.

While her presence in the pantheon of ancient Egyptian gods during the Predynastic Period (c. 6000-3150 BCE) is believed to have been minor, she rose to prominence in later periods, particularly as part of the Theban Triad.

In the early stages of Egyptian civilization, Mut’s role was likely overshadowed by other mother goddesses. However, with the rise of Thebes as a significant religious and political center, Mut gained considerable importance.

She became associated with Amun, the god of the sun and air, and Khonsu, the moon god, forming the revered Theban Triad.

As the wife of Amun and mother of Khonsu, Mut embodied the aspects of motherhood, family, and royalty.

She was often depicted as a woman wearing the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt, signifying her authority and status.

In some representations, she appears with lioness features or as a vulture, symbols associated with motherhood and protection in ancient Egyptian culture.

The Temple of Mut in Karnak, part of the vast Karnak Temple Complex in modern-day Luxor, stands as a testament to her significance. This sanctuary, dedicated to her worship, showcases her elevated status in Theban society and the broader Egyptian pantheon.

Khonsu – The Traveler and God of the Moon

Khonsu, also known as Kons, Chonsu, Khensu, or Chons, is a significant deity in the ancient Egyptian pantheon of gods. Known as ‘The Traveler,’ he was venerated as the god of the moon, symbolizing time, visibility, and rejuvenation.

Khonsu’s name, which translates to ‘The Traveler,’ reflects his association with the moon.

As the moon travels across the sky, marking the passage of time, Khonsu was believed to govern time itself. This connection made him an essential figure in Egyptian lunar and calendar systems.

The importance of Khonsu extended beyond his lunar associations.

He formed one-third of the influential Theban Triad, alongside his father Amun, the god of the sun and air, and his mother Mut, the mother goddess.

The triad was central to the religious practices in Thebes, one of the most powerful cities in ancient Egypt. Each member of this divine family held a specific role, with Khonsu embodying youth and renewal.

In ancient Egyptian art, Khonsu is often depicted as a mummiform child, signifying his role as the youthful moon god. He is usually shown wearing a sidelock of youth and holding the crook and flail, symbols of kingship. His head is adorned with a moon disk and crescent, emphasizing his lunar associations.

The Temple of Khonsu, part of the Karnak temple complex in modern-day Luxor, is a testament to his reverence. This dedicated space for worship attests to Khonsu’s significance within the Theban Triad and his influence on the religious practices of ancient Egypt.

Amunhotep, Son of Hapu – The Deified God of Healing and Wisdom

Amunhotep, son of Hapu, is known for his contributions to healing and wisdom.

Unlike the majority of ancient Egyptian gods, Amunhotep was a real historical figure who achieved a rare honor – he was deified by the Egyptians, joining the ranks of Hardedef and Imhotep.

Born in the 18th Dynasty under the reign of Pharaoh Amenhotep III, Amunhotep, son of Hapu, was a high-ranking official and architect.

He was responsible for several monumental constructions, including the funerary temple of Amenhotep III on the West Bank at Thebes. His wisdom and contributions to architecture were highly recognized, leading to his posthumous veneration as a god of wisdom.

In addition to wisdom, Amunhotep was also revered as a god of healing. His healing powers were considered so significant that sick people would inscribe their ailments on stelae, or stone pillars, at his mortuary temple in Thebes, hoping for divine intervention.

The popularity of Amunhotep’s cult grew in the Late Period (664-332 BCE) and continued through the Ptolemaic Period (332-30 BCE). Temples dedicated to him can be found throughout Egypt, showcasing his widespread influence and the enduring respect for his wisdom and healing abilities.

Amunhotep’s transition from a human being to a deity underscores the fluid nature of the pantheon of ancient Egyptian gods. His deification represents an intriguing aspect of Egyptian culture, where exceptional human beings could achieve divine status through their wisdom and contributions to society.

Hardedef – The Deified Son of King Khufu and Author of ‘Instruction in Wisdom’

Hardedef, also known as Hordjedef, holds a unique place in ancient Egyptian history and mythology.

As the son of King Khufu (also known as Cheops, 2589-2566 BCE), he was born into royalty. However, his lasting legacy extends beyond his royal lineage, primarily due to his authorship of a remarkable work known as the ‘Instruction in Wisdom.’

The ‘Instruction in Wisdom’ is considered one of the earliest pieces of ‘wisdom literature’ from ancient Egypt. This genre typically includes advice on moral conduct, practical life lessons, and philosophical reflections, aimed at guiding the reader towards a virtuous and successful life.

Hardedef’s contribution to this literary tradition showcases his intellectual prowess and deep understanding of human nature and morality.

What sets Hardedef apart is the level of reverence his work received. His ‘Instruction in Wisdom’ was so brilliant and impactful that it was considered divine in origin.

This extraordinary recognition led to his deification after death, an honor bestowed upon very few individuals in ancient Egypt.

As in the case of Amunhotep and Imhotep, Hardedef’s deification represents a fascinating aspect of ancient Egyptian culture, where the boundary between the human and the divine could be blurred.

Exceptional wisdom and contributions to society could elevate a mortal to the pantheon of ancient Egyptian gods, highlighting the profound respect for knowledge and wisdom in ancient Egypt.

Imhotep – The Polymath Vizier and Deified God of Wisdom and Medicine

Imhotep, whose name translates to “He Who Comes in Peace,” was a remarkable figure in ancient Egyptian history.

Living roughly between 2667-2600 BCE, he served as the vizier to King Djoser and is renowned for his significant contributions to architecture, wisdom, and medicine.

His exceptional abilities and accomplishments ultimately led to his deification, marking him as one of the few mortals in ancient Egypt to achieve divine status.

As the chief adviser to King Djoser, Imhotep held a position of great authority and influence. However, it is his architectural ingenuity that has left the most enduring mark on history.

He is credited with the design and construction of the Step Pyramid at Saqqara, the first colossal stone building and the earliest colossal stone pyramid in Egypt. This architectural marvel set a precedent for future pyramid constructions and stands as a testament to Imhotep’s innovative spirit.

Beyond his architectural achievements, Imhotep was also a polymath, demonstrating expertise in various fields of study. His wisdom was highly valued, and he is often considered one of the first known philosophers. His teachings and sayings were studied and revered for thousands of years after his death.

In addition to his wisdom, Imhotep was associated with medicine, making significant contributions to the field. His medical treatises provided insights into ancient Egyptian practices and knowledge, further enhancing his reputation as a man of wisdom and learning.

Following his death, Imhotep’s extraordinary contributions to society led to his deification.

He was venerated as a god of wisdom and medicine, a rare honor that underscores his unique role in ancient Egyptian history. Temples were erected in his honor, and he was invoked by the sick and injured in their prayers for health and healing.

Asclepius (Aesculapius) – The Greek God of Healing

Asclepius, known to the Romans as Aesculapius, is a significant deity within Greek mythology, renowned for his healing abilities.

Famed as the god of medicine and healing, Asclepius’s influence extended beyond Greece’s borders, reaching the ancient Egyptians who also held him in high regard.

In Egypt, Asclepius was worshipped primarily at Saqqara, an extensive ancient burial ground serving as the necropolis for the ancient Egyptian capital, Memphis.

Here, the god of healing gained a new identity, becoming associated with Imhotep, a revered Egyptian figure.

The identification of Asclepius with Imhotep highlights the shared value both cultures placed on healing and medicine. It also illustrates the fluidity of ancient mythology, where gods could transcend cultural boundaries, adapting to local contexts while maintaining their core attributes.

Asclepius’s cult in Egypt reflected this syncretism, blending Greek and Egyptian religious practices.

Healers and patients alike would invoke Asclepius-Imhotep, seeking divine intervention for ailments. Temples dedicated to the god served not only as places of worship but also as healing centers, reinforcing the practical application of the deity’s domain.

Ash (As) – The Oasis Provider in the Libyan Desert

Ash, also known as As, is a deity hailing from ancient Egyptian mythology, revered as the god of the Libyan desert.

Unlike the harsh and unforgiving nature often associated with desert deities, Ash stands out as a benevolent figure.

He is celebrated for providing oases to weary travelers journeying through the vast, arid expanses.

The Libyan desert, part of the greater Sahara Desert, is an extensive, challenging landscape.

Travelers crossing this desert face extreme conditions, including scorching heat during the day, freezing cold at night, and the constant threat of deadly sandstorms.

In this harsh environment, the appearance of an oasis could mean the difference between life and death.

Ash’s role as the provider of these life-saving oases marks him as a symbol of hope and survival. His gifts of water and shelter offered not only physical relief but also a psychological respite, giving travelers the strength and will to continue their journey.

His veneration underscores the ancient Egyptians’ deep understanding of their environment and their respect for the forces that shaped it. It also highlights their belief in the power of divine intervention, placing their trust in Ash to guide them safely through the perilous desert.

Hedetet – The Scorpion Goddess

Hedetet held a significant position in the pantheon of ancient Egyptian gods, primarily due to her role as a protectress against scorpion venom.

Scorpions were common in ancient Egypt, posing a serious threat to humans with their venomous stings.

In this harsh context, Hedetet emerged as a divine shield, offering protection against these lethal creatures. Her worship underscored the Egyptians’ respect for the natural world’s dangers and their faith in divine intervention for survival.

Hedetet is often considered an early version of Serket, another Egyptian goddess associated with scorpions. Like Hedetet, Serket was revered as a protector against venomous stings.

However, Serket’s influence expanded beyond this role, encompassing healing, magic, and protection of the pharaoh. Despite these differences, the connection between Hedetet and Serket illustrates the evolution of religious beliefs and practices in ancient Egypt.

Serket – The Protective and Funerary Goddess

Serket, also known as Selket, Serqet or Serkis, is an ancient Egyptian goddess with a role that extends beyond protection to encompass funerary rites.

Her origins likely date back to the Predynastic Period (c. 6000-3150 BCE), making her one of the earliest revered deities. She is first mentioned during the First Dynasty of Egypt (c. 3150-2890 BCE), testifying to her longstanding importance in Egyptian worship.

Best known from her golden statue discovered in Tutankhamun’s tomb, Serket’s depiction is both unique and symbolic.

She is often portrayed as a woman with a scorpion resting on her head, her arms extended in a protective pose. This imagery reflects her dual role as the guardian against venomous stings and a defender of the divine order.

Serket’s association with scorpions links her to the goddess Hedetet, believed to be an earlier incarnation of Serket.

Both goddesses share the scorpion as their emblem, symbolizing their protective powers against the dangers of the natural world.

In addition to her protective role, Serket was also an important figure in funerary rites.

Her presence in Tutankhamun’s tomb attests to her crucial function in guiding and safeguarding the deceased in their journey to the afterlife.

This funerary aspect of Serket showcases the Egyptians’ deep-rooted beliefs in life after death and the divine intervention needed for a successful transition.

Meskhenet – The Goddess of Childbirth

Meskhenet is the goddess of childbirth and destiny. Often depicted as a woman with a birthing brick on her head – a nod to the traditional Egyptian method of assisting women in delivery by having them squat or kneel on bricks – Meskhenet was believed to be present at every birth, bestowing a child’s fate at the moment they entered the world.

Beyond her role in childbirth, Meskhenet was also associated with the concept of ka, an element of the soul in ancient Egyptian belief.

She was thought to help shape a person’s ka, which would then accompany them throughout their life, influencing their character and destiny.

Interestingly, Meskhenet’s influence extended into the afterlife.

In the Book of the Dead, she is depicted as one of the deities presiding over the Weighing of the Heart ceremony. This critical event determined whether a deceased person could enter the afterlife, further emphasizing Meskhenet’s role in deciding human fate.

Meskhenet’s story offers a glimpse into how the ancient Egyptians understood life’s critical events, from birth to death. As the goddess of childbirth, she was seen as a guardian of life’s beginning, while her role in the afterlife reflected her continued guidance beyond mortal existence.

Montu – The Falcon God

Montu, the falcon god, is a significant figure in ancient Egyptian mythology and the pantheon of gods, especially during the 11th Dynasty in Thebes.

Often depicted as a man with the head of a falcon, Montu was revered as the god of war and a symbol of royal power.

As his cult grew in prominence, he became closely associated with the Theban region, which was a major political and cultural center of ancient Egypt during the Middle Kingdom.

Montu’s rise to prominence coincided with the ascendancy of Thebes and its rulers.

The Theban kings, particularly those of the 11th Dynasty, saw Montu as their divine patron and often referred to themselves as “Montu in the palace” to signify their divine right to rule and their prowess in warfare.

They built several temples dedicated to Montu in the Theban region, including the Temples of Montu at Medamud and Tod, further cementing his status as a powerful deity.

Beyond his martial attributes, Montu was also associated with the sun god Ra. He was often depicted in solar iconography, reinforcing his status as a powerful divine entity.

Despite this, his primary role remained as a symbol of military strength and royal authority, reflecting the cultural and political realities of the time.

The story of Montu provides a fascinating insight into the interplay between religion and politics in ancient Egypt. His prominence during the 11th Dynasty underscores how deities were often used to legitimize and reinforce royal power, illustrating the intricate relationship between the divine and the mortal realms in ancient Egyptian society.

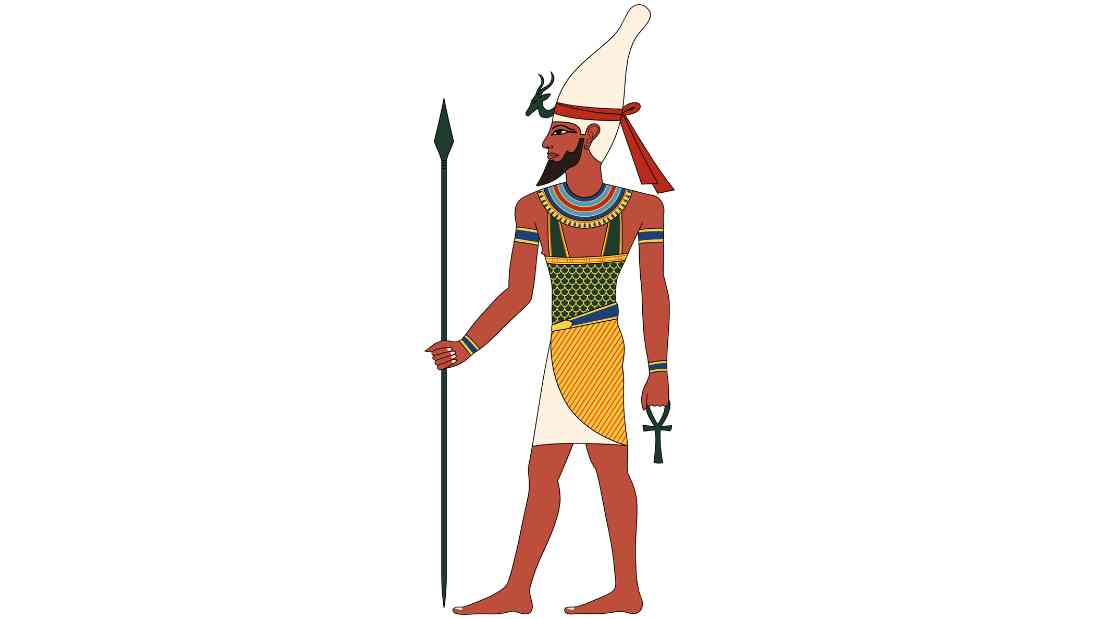

Anhur – The God of War and Hunting

Anhur, also known as Onuris, was revered as a god of war and hunting, embodying strength, courage, and skill.

His name, which translates to “He Who Brings Back The Distant One,” is not merely a title but a testament to his role in one of the most significant myths of ancient Egypt.

The tale referred to by his name involves a quest to retrieve the Eye of Ra, a powerful symbol of protection and destructive force in ancient Egyptian religion.