The Ancient Egyptians had a cultural ethos that was deeply rooted in the concept of Maat or Ma’at. Maat was not just a goddess in the Egyptian pantheon but represented a complex framework of order, truth, and justice. Central to these principles were the 42 Laws of Maat, which provided a moral and spiritual code that guided the Egyptians in their daily lives and their understanding of cosmic harmony.

In post, we’ll delve into these ancient principles of Maat and see how they reflect the perennial quest of the ancient Egyptians for balance and righteousness.

Understanding the Goddess Maat: The Foundation of Ancient Egyptian Cosmology

To fully grasp the profound impact of the 42 Laws of Maat on ancient Egyptian civilization, we must first delve into the essence of Maat herself.

Maat, or Ma’at, was not merely a goddess in the traditional sense. She was the embodiment of an all-encompassing truth that governed both the cosmos and the societal order of the Nile valley’s inhabitants.

Maat represented the intrinsic force that maintained the universe’s balance. She was integral to the very fabric of existence, from the predictable flooding of the Nile, which ensured fertile soil, to the overarching moral codes that dictated human conduct.

In essence, Maat was the harmonizing element between the physical and the metaphysical, between earthly living and the divine.

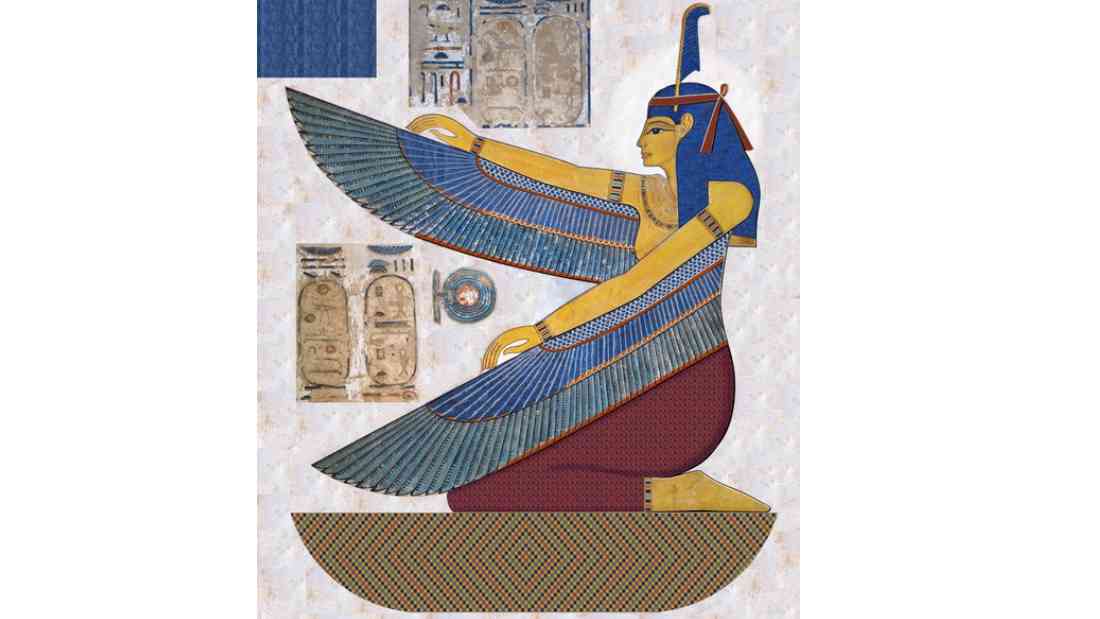

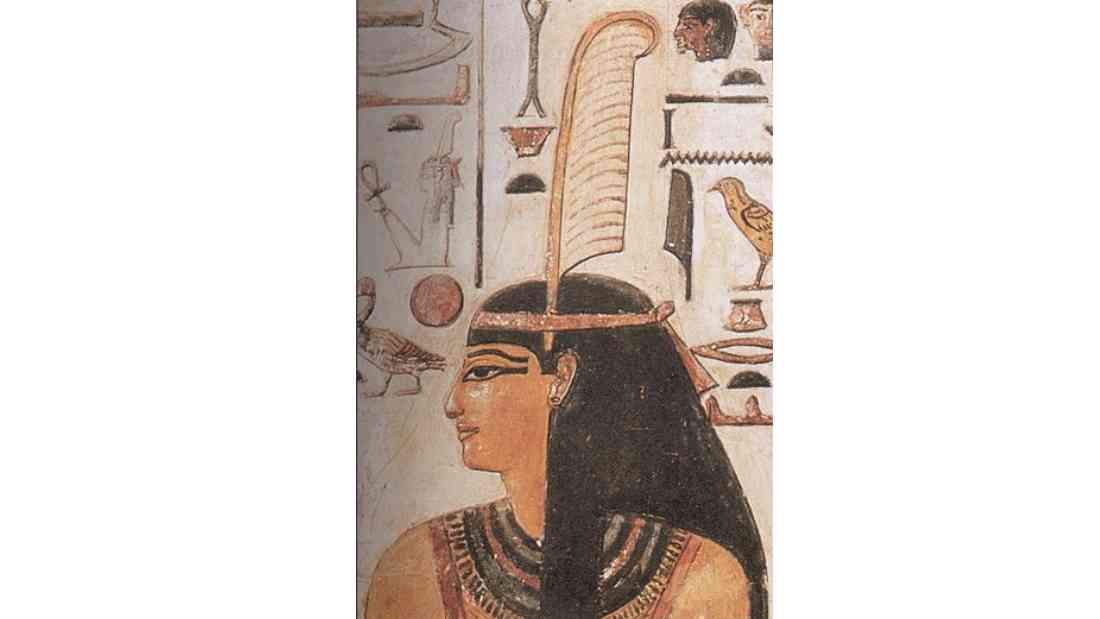

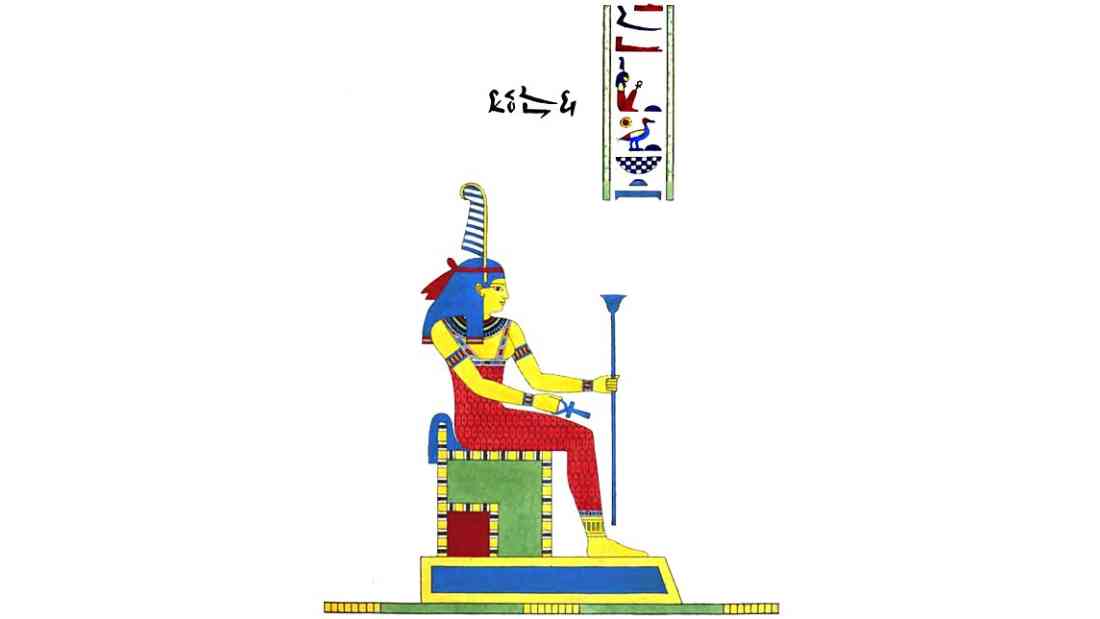

Her iconography is rich with symbolism. Maat is most commonly depicted as a woman with wings or, more famously, with an ostrich feather adorning her head.

This feather, known as the “Feather of Truth,” served as a potent emblem of her authority and the ideal of balance. It was against this feather that the hearts of the deceased were weighed in the afterlife, according to the ‘Book of the Dead,’ a fundamental mortuary text of ancient Egypt.

For the pharaohs, who were charged with the maintenance of Maat throughout the land, their connection to her was paramount.

They were considered the “Chosen of Maat” and were believed to have a divine mandate to uphold her principles.

The representation of pharaohs making offerings to Maat was not merely symbolic but also a public declaration of their commitment to justice and societal order.

Without Maat, chaos, known as isfet, would reign, a state that was antithetical to the continuation of life and the order of the cosmos.

The 42 Laws of Maat

The 42 Laws of Maat, also referred to as the negative confessions or declarations of innocence, were the spiritual statutes by which every Egyptian aspired to live. These confessions covered a broad spectrum of ethical conduct, from the most fundamental human interactions to the profound responsibilities towards the gods and the natural world.

The laws outlined a standard for ethical and moral conduct.

Here is a list of all 42 declarations:

- I have not committed sin.

- I have not committed robbery with violence.

- I have not stolen.

- I have not slain men and women.

- I have not stolen food.

- I have not swindled offerings.

- I have not stolen from God/Goddess.

- I have not told lies.

- I have not carried away food.

- I have not cursed.

- I have not closed my ears to truth.

- I have not committed adultery.

- I have not made anyone cry.

- I have not felt sorrow without reason.

- I have not assaulted anyone.

- I am not deceitful.

- I have not stolen anyone’s land.

- I have not been an eavesdropper.

- I have not falsely accused anyone.

- I have not been angry without reason.

- I have not seduced anyone’s wife.

- I have not polluted myself.

- I have not terrorized anyone.

- I have not disobeyed the law.

- I have not been exclusively angry.

- I have not cursed God/Goddess.

- I have not behaved with violence.

- I have not caused disruption of peace.

- I have not acted hastily or without thought.

- I have not overstepped my boundaries of concern.

- I have not exaggerated my words when speaking.

- I have not worked evil.

- I have not used evil thoughts, words or deeds.

- I have not polluted the water.

- I have not spoken angrily or arrogantly.

- I have not cursed anyone in thought, word or deeds.

- I have not placed myself on a pedestal.

- I have not stolen what belongs to God/Goddess.

- I have not stolen from or disrespected the deceased.

- I have not taken food from a child.

- I have not acted with insolence.

- I have not destroyed property belonging to God/Goddess.

These declarations covered a wide array of transgressions, addressing not only physical acts but also moral and spiritual ones. They were designed not just as a legalistic framework but as a holistic approach to living a life that was in alignment with the order of the universe.

The Journey to Duat

During the journey that the soul takes in the Egyptian underworld, known as Duat, it encounters a formidable tribunal comprising 42 divine judges, each representing one of the unified provinces, or nomes, of Egypt at the time.

The ancient Egyptians believed that these 42 deities embodied the laws of Maat and served as guardians of the cosmic order, overseeing the moral and ethical fabric of society.

In the presence of these divine adjudicators, the deceased would assert their adherence to each law, effectively proclaiming a life lived in harmony with Maat’s precepts.

Each invocation before the divine judges was a testament to the deceased’s character, a declaration that they had not committed sins ranging from theft and falsehood to environmental harm and sacrilege.

The culmination of this ritual was the symbolic weighing of the heart against the feather of Maat. Should the heart be found lighter or equal in weight to the feather, the soul was judged worthy of progressing to Aaru, the field of reeds, an idyllic representation of paradise where the soul would exist in eternal contentment.

The Worship of the Ancient Egyptian Goddess Maat

In temples across Egypt, statues and inscriptions of Maat served as constant reminders to the people and the priesthood of the importance of maintaining cosmic equilibrium.

The 42 principles of Maat permeated every aspect of Egyptian life, from the judicial system to agricultural practices, from architectural designs to the religious ceremonies that sought the favor of the gods.

Maat’s principles also extended to personal virtue and integrity, laying the groundwork for a society where mutual respect and moral rectitude were held in the highest regard.

The concept of living in truth, or “maa kheru,” was not only desired but required for one’s soul to successfully achieve the afterlife.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the 42 Laws of Maat consisted of principles that provided both a guide for living an upstanding life and a framework for the judgment of souls in the afterlife.

These laws were recited as declarations of innocence in front of 42 divine judges, encapsulating a range of ethical norms from honesty and justice to respect for property and the sanctity of family. Adherence to these laws ensured that the deceased could claim a place in Aaru, the idyllic paradise of eternal contentment.

Posts About the Egyptian Pantheon of Gods

The Pantheon of Ancient Egyptian Gods – A Comprehensive Guide

The Wrath of Montu – The Mythology of the Egyptian War God

Egyptian God Ammit – The Eater of Hearts in Ancient Egyptian Mythology

The Nightly Journey of Khonsu – The Ancient Egyptian God of the Moon

Ihy – The Joyful Ancient Egyptian God of Music

Min – The Ancient Egyptian God of Fertility

The Egyptian God Anubis – His Evolution from Son of Ra to Protector of the Dead

Unraveling the Mysteries of Babi – The Ancient Egyptian Baboon God

Ra, the Egyptian Sun God – Symbolism and Significance in Ancient Egyptian Culture

Sobek: The Ferocious Crocodile God of Ancient Egypt

The Enigmatic Mythology of Horus, the Egyptian Sky God

The Egyptian God Set – Protector of the Desert and Lord of Conflict

The Ancient Egyptian God Medjed: The Guardian of Osiris and the Afterlife

Anput, the Wife and Female Version of Anubis

Selket – The Scorpion Crowned Egyptian Goddess

Shu – The Egyptian God of Air, Wind, Peace and Lions

Hapi the Androgynous Ancient Egyptian God of the Nile

The Egyptian Sky Goddess Nut: Myth and Symbolism

The 42 Laws of Maat: The Moral Principles of the Ancient Egyptians

The Ancient Egyptian Goddess Mut: The Maternal Power in Egyptian Mythology

The Warrior Goddess: Neith in Ancient Egyptian Mythology

The God Bes: The Joyful Dwarf Deity in Ancient Egyptian Culture

The Egyptian Gods of Love: Hathor and Isis in Ancient Egyptian Mythology

Confronting the Serpent: The God Apep, the Nemesis of Ra in Egyptian Myth