The aim of this essay is to analyse whether symbolic kinship and sacrifice reinforce the legitimation of the Nation State. To explore this I will be using Katherine Verdery’s 1991 book, The Political Lives of Dead Bodies: Reburial and Postsocialist Change, and a chapter entitled Heirs of Antigone: Disappearances and Political Memory from Paul Sant Cassia’s 2007 book, Bodies of Evidence.

In order to understand what is being examined we must first understand what is meant by legitimation. This term can be understood in different ways. The word legitimation evokes the idea that an entity’s exercise of power is justified. That being said, the legitimation of an entity isn’t infinite as it also sets moral and ethical boundaries based on norms and values on those in authority (Seymour-Smith, 1986). It follows then, that those in authority have a legitimate right to govern. Authoritative entities, such as states or churches thus have the right to make decisions affecting those who hold them to also be legitimate entities.

In the first chapter of his book, Sant Cassia (2007) points out that the protagonist in the play Antigone, Creon, “confuses power with legitimacy” (pp.8) as he exercises authoritarianism over the Greek city of Thebes. Whilst coercion can be used to control followers, it cannot achieve legitimation alone.

In fact, as Sant Cassia (2007), conveys, the ‘heroin’ in the Greek tragedy, Antigone gains sympathy as she tries to give her brother a proper burial, resulting in her losing her beloved and leading to her untimely death by suicide. It should also be noted that while Creon survived and continued to rule, he lost those important to him – his wife and son also die by suicide.

This play remains of importance to this day as we are still dealing with the same dilemmas now, those being of state versus individual; law versus justice and even human law versus divine law.

This begs the question – How does a nation state gain legitimacy?

To discuss this question, we must first look to what the state desires to have authority over. As Vuk Draskovic, a Serb nationalist stated, ‘Serbia is wherever there are Serbian graves’. These words inspire a sense of belonging and of comradeship for Serbians who personified their country as Mother Serbia. This further conveys that they are descendants of their land and that by their land, the Serbs are brothers and sisters.

The same symbolic kinship is seen in other countries such as Russia, Malta and Britain and this reinforces the idea of ethnic identity.

In his text, Sant Cassia (2007) highlights the problem that this idea of kinship might face when dealing with clashing interests of the people that cold clash with that of the state. The above quotation also relates to Sant Cassia’s (2007) work where he states that burial involves two intertwined aspects.

Whilst it created community by reinforcing an idea of membership and the idea that a piece of land belong to the community it also connects the living to their ancestors and what has been passed down to them. When considering this, one does not find it hard to understand why the Greek Cypriot women mentioned in Sant Cassia’s (2007) text were determined to find their husbands’ missing bodies.

With land comes soil, which according to Verdery (1999), holds great significance for many societies. She relates that societies include and are affected by both their living and their dead (Verdery, 1999). Thus the lives once lived by the deceased members of a community and their burial are of great concern to the living members (Verdery, 1999).

Moreover, different societies have different norms and rituals but one that sticks out is that of homecoming – the idea that a person belonging to a certain ethnic identity should be buried in the soil of their ancestors.

This is exhibited in the case of the Transylvanian Bishop Inochentie Micu who died in 1768 but whose story still kept on developing until towards the end of the 20th century. Whilst the reburial didn’t gain a lot of media coverage and was followed by a small group of people, it was surrounded by controversy (Verdery, 1999).

After the rule of the Communist Party in the Soviet Union collapsed, there was a religious resurgence in the country. At the time, the most popular religion was Greek Orthodoxy, however, other religious groups such as the Roman Catholic Church and Protestant churches were also significant. This renewal of religious faith resulted in competition between the churches.

Due to the century coming to a close and a new millennium being ushered in, Verdery (1999) suggests that this could have been an opportunistic move by the Catholic Church to return the body of a national treasure and gain some publicity. In return, the Romanians got to bury their national hero, on their land and soil. Although Inochentie Micu was buried in Rome in 1768, his body could be considered to have been ‘laid to rest’ after his repartition to his homeland of Transylvania, Romania in July 1997.

Inochentie Micu is also of great importance to the Romanians as he is regarded as a national hero. Whilst the two dominant Churches revelled in different aspects of his life for several reasons – he was a hero in both churches and in all of Romania.

The reason why they held him in such high regard was due to the sacrifice he made. This sacrifice echoes and resonates with the Romanians who as a country have struggled for a long time. In 18th century Transylvania, there were three different language speaking groups (Verdery, 1999). Each one of these groups had an accepted faith/s and also tended to have a different ranking in society. Inochentie Micu was descended from a Romanian family of Eastern Orthodox faith (Verdery,1999).

A large number of nobleman, as Verdery (1999) conveys had followed a Protestant faith. For the Catholic ruling House of Hubsburg, which was already facing adversary, this was viewed as a problem. In order to bring some stability to their reign, they strove to convert the noble Protestants and Orthodox serfs to Catholicism.

In pursuit of achieving this, the Habsburgs merged the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches into the Greek Catholic Church. The added incentive for their prey (who were largely Orthodox serfs) was that if they were to join this church they would be given the same privileges as the Catholic church. This came into fruition when higher clergyman of the Romanian Orthodox Church converted to the Greek Catholic faith. Inochentie Micu took on the role of the Greek Catholic bishop in 1729 and as a result, also gained the title of baron.

In his role Inochentie Micu advocated that the Romanians receive the privileges they were promised as newly converted Catholics (Verdery, 1999). He worked towards this goal for 40 years, converting Romanians and fighting for their rank to be raised to ‘natio’ (Verdery, 1999). By doing this he was working towards the betterment of the Romanian ethnic identity.

Despite all this, he also struggled and had to sacrifice his residence by living in exile from 1744 and having to abdicate from his role in 1751 (Verdery, 1999). This occurred due to all the hatred he had generated from the reigning monarch and the nobleman of the time as they had no interest in ending the feudal labour force (Verdery, 1999).

After a life of suffering, Inochentie Micu enjoys admiration in the afterlife from the Romanians he fought for. The Orthodox nationals believe he fought for the relief of his people from the forced burden of labour whilst being masked as a Greek Catholic whilst for the Greek Catholics he fought for the validation of their religion (Verdery, 1999).

By shifting our attention now to prose, a similar story is portrayed in Antigone. Sophocles’ heroin was at war with her Uncle Creon because she wants to give her brother a proper burial. The play relates that while her brother wasn’t a kind person, his sister still wishes to give him a proper burial in order to lay him to rest, lessen the shame of his memory and avoid a curse on the land (which would occur according to Greek tradition).

This is met with contention from Creon who considers her brother to be a traitor and who had already passed judgement on the fate of his burial. Creon wants to abide by the state and laws, and thus, when Antigone goes against his orders and buries her brother she too is punished by being buried alive.

By the end of the tragedy, whilst the focus is on Antigone’s sacrifice, there is an element of sacrifice in Creon’s story too – his quarrel with his niece cost him his family. That being said, by upholding state law, he continued to rule. As Sant Cassia (2007) relates, “For Creon there are no individuals, just principles”(pp.8).

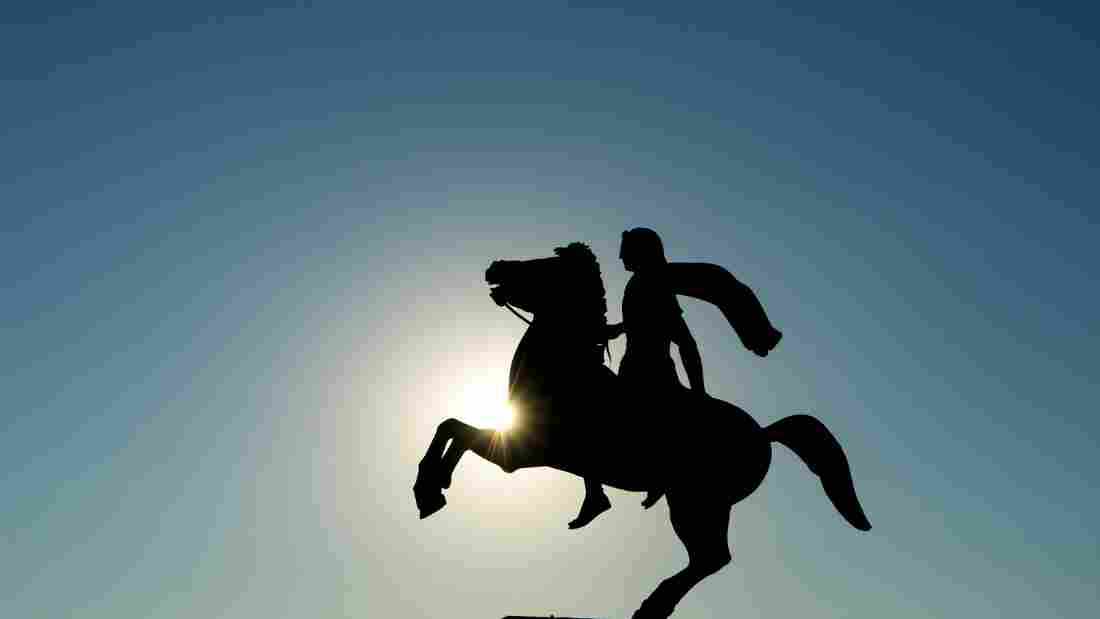

Taking this into account, underlines that legitimation does in fact limit power. Even those in the ruling class have to sacrifice something for the right to rule, if not for the sake of the nation, for the sake of keeping up appearances. The dominant ruling class can also use statues to project the appearances they would like to portray.

Through the sacrifice of these heroes, they are in turn, adopted by the ethnic group as one of the prominent figures of their community. In remembrance of their work or sacrifice, statues may be erected in their honour. This action gives these figures the image of an icon and thus there is an element of idolisation (Verdery, 1999).Incidentally these figures tend to be adopted into the ethnic identity as an important familial person.

Consequently, one disrespecting a certain statue would be impious as they would not only be dishonouring the memory of the person but also they would be disparaging a symbol which is highly regarded to the state who put it there. Moreover, removing or replacing the statues of figures represents a change in ideology (Verdery, 1999). This could be exemplified by the removal of Lenin’s statues in the post-socialism era (Verdery, 1999)

Eeading Sant Cassia’s (2007) approach on the Greek tragedy Antigone and Verdery’s (1999) book on post-socialism it is obvious that whilst the world has changed in many aspects, it still faces similar political issues. People and nations still put great emphasis on symbolic kinship and what it is to be part of an ethnic group and the need to represent and protect that image. States still use political heroes and glorify their sacrifices because it reinforces ethnic and national identity. Thus whilst many other factors play a part in the structure of nation sates, it can be argued that they do gain legitimation through symbolic kinship and sacrifice.

Bibliography

Cheater, A. P., 1989. Ideology and Social Control, Social Anthropology: an alternative introduction. New York: Routledge, pp. 166-184

Cheater, A. P., 1989. Ideology and the State, Social Anthropology: an alternative introduction. New York: Routledge, pp. 185-200.

Sant Cassia, P., 2007. HEIRS OF ANTIGONE: Disappearances and Political Memory , Bodies of Evidence: Burial, Memory and the Recovery of Missing Persons in Cyprus. Oxford: Berghahn Books, pp. 1-17. URL = *Antigone-PSC.pdf

Seymour-Smith, C., 1987. Macmillan Dictionary of Anthropology. London: The Macmillan Press.

Sypnowich, C., 2019. Law and Ideology, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Zalta, E. N. (ed.), URL = https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2019/entries/law-ideology/ .

Verdery, K., 1991. THE POLITICAL LIVES OF DEAD BODIES: Reburial and Postsocialist Change. New York: Columbia University Press. URL= *Verdery Political Lives of Dead Bodies .pdf