In this essay I will be focusing on the differences between the approaches taken by Bloch and Leinhardt in their analysis of the rituals of the Merina and the Dinka, highlighting how the former focuses on how religion underpins, legitimises and mystifies the politics, economics, and kinship structures of a society, while the latter highlights the impact of ritual on the moral experience of participants, thereby changing the way people think about themselves and their place in the world.

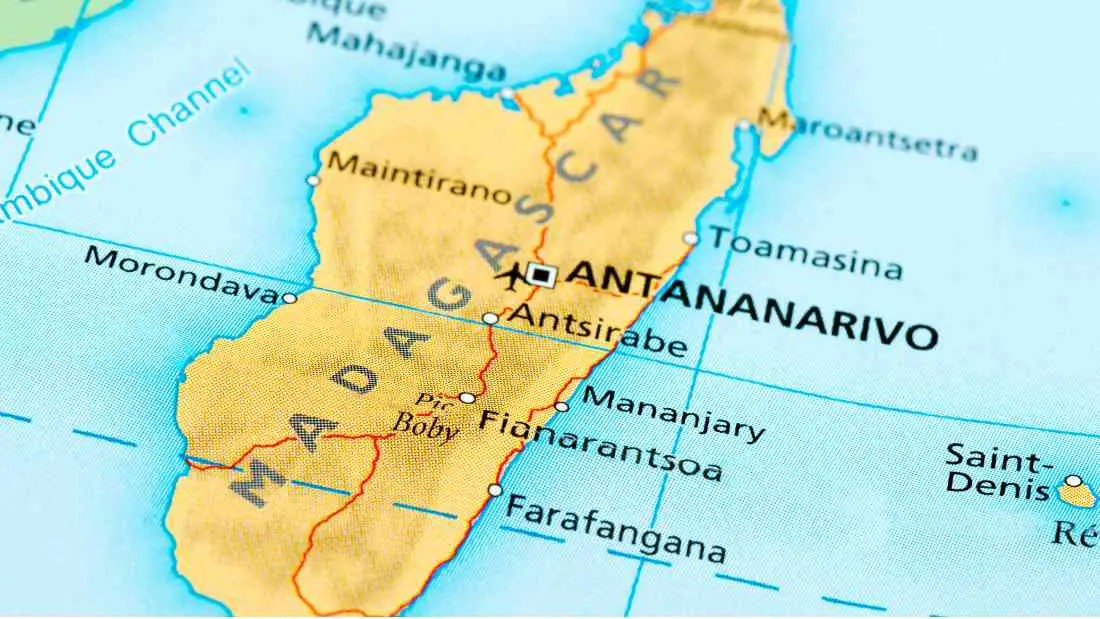

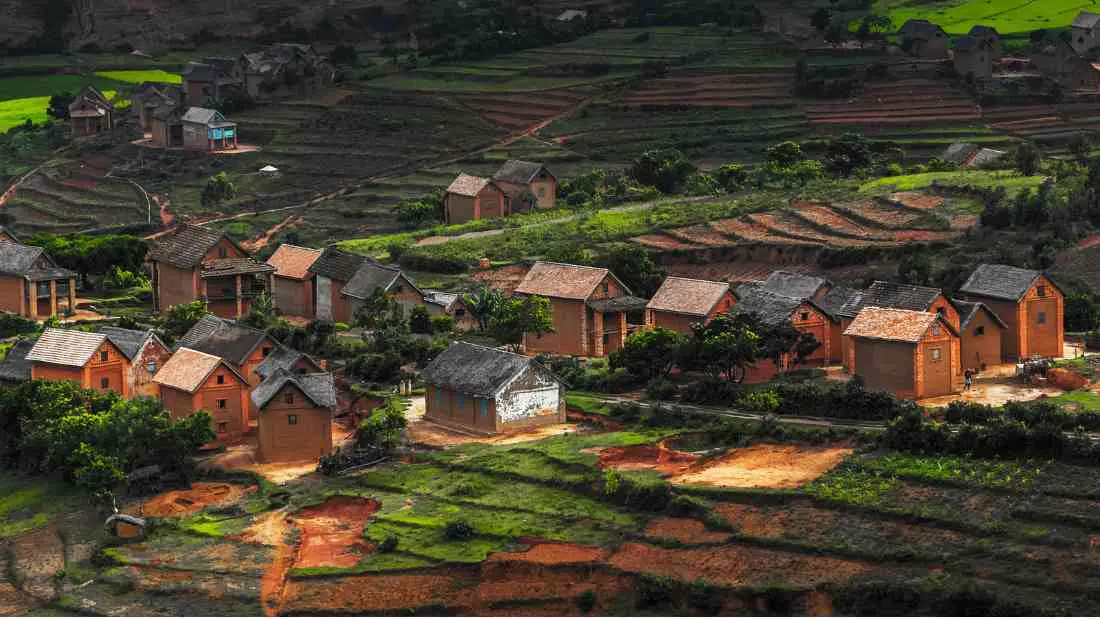

Bloch’s analysis of the Merina highlights the significance of their religion as the ideological foundation of their society.

He does this by analysing their social structure and their mythology, showing that the Hasina/ Masina rituals serve to legitimise existing politico-economic power structures, ultimately reinforcing and sacralising their ruler’s authority by mystifying his role as the source of hasina, a type of life force which is intimately connected with fertility.

To illustrate how this works I will be referring to the rituals associated with the coronation of a new king and the annual ritual of the royal bath, both of which are fundamental to establishing and maintaining the authority of the king and the aristocracy.

When a new king is crowned, one of the most important stages of the coronation ritual involves him drinking water obtained from the graves of previous rulers.

This symbolizes the link between past rulers and the present, legitimizing the new king, who would not usually be a blood relative of the previous rulers and thus has no claims to kingship through lineage.

The coronation ritual, and more specifically the part where the new ruler drinks the water from the graves of previous rulers, manufactures a form of spiritual descent, through which the royal life force is transmitted to the new ruler, making it possible for him to claim his role as the new source of hasina and giving him legitimacy in the eyes of the population.

Another ritual that is extremely important in reinforcing the authority of the king, as well as that of the aristocracy, is the annual royal bath.

The preparations for the bath involve the entire population paying hasina upwards, in the form of unbroken coins.

Younger brothers give coins to their older brothers, who give coins to their fathers, who then give coins to the person next up in the rank, all the way up to the aristocracy and finally to the ruler, in what is clearly a re-enactment of the social order, supporting the ruling class and reinforcing the status quo.

On the day of the royal bath the ruler bathes in water obtained from several sacred sites, once again emphasizing his sacred role as the bearer of hasina.

When he emerges from the bath, he sprays the water onto his subjects, passing on his life force and fertility to them.

Bloch’s analysis of these two rituals highlights how religion and ritual are used to maintain power structures and reinforce social hierarchies.

By emphasizing the sacredness of the ruler and his role in providing hasina for his people, these rituals legitimize his power and ensure the stability of the political order.

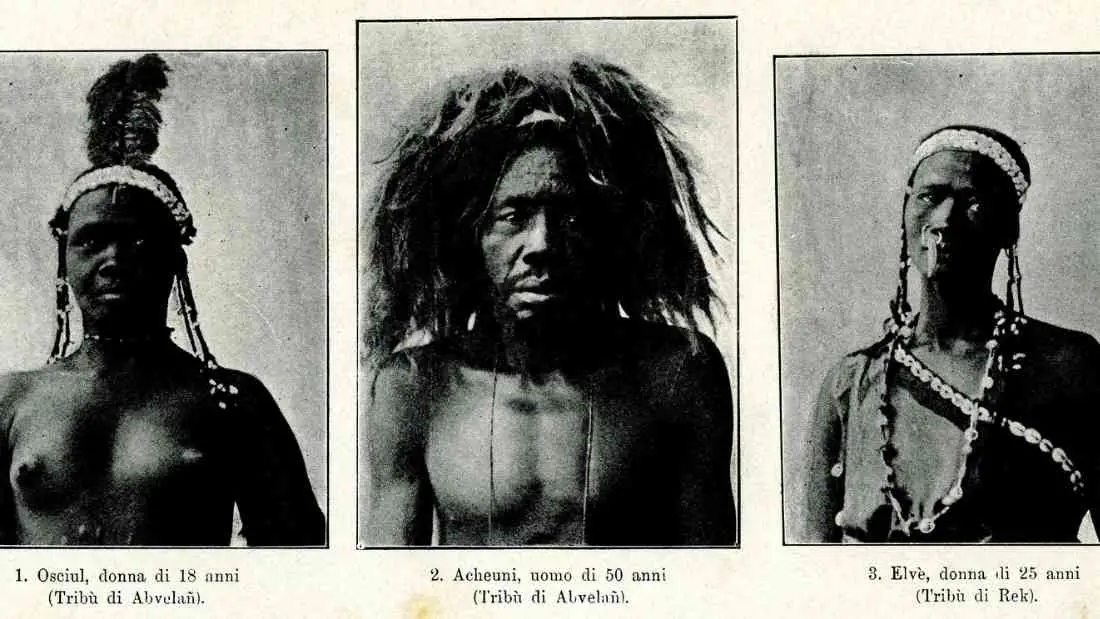

Now I will shift the focus to Lienhardt’s interpretation of the sacred experience of the Dinka and his analysis of the symbolic and moral significance of their rituals.

Unlike Bloch, Lienhardt attempts to understand the achievements of religion on its own terms and how ritual can have a profound transformative impact on individuals and societies.

His work emphasizes the symbolic and moral dimensions of religion and highlights the importance of examining its implications for human experience as well as social structures.

The examples I will refer to are the Dinka rituals relating to incest and peace-making, and the transformative impact they have on the moral experience of participants.

Leinhardt’s analysis of the Dinka ritual for incest shows how couples are cleansed of their sin, thus avoiding its consequences.

The master of the spear recites incantations over the couple, and they are washed by their kinsmen in a pond of water.

An animal, such as a ram or a bull, is forcefully pushed under the water, and symbolically the sin of the couple transfers from them to the animal through the water.

The animal is then cut in half lengthwise, through the sexual organs, the splitting of which symbolizes the retroactive nullification of the incestuous relationship.

This symbology, intent and effect of this ritual echoes the nullification ritual performed by the Zande in cases of serious incest, as described by Evans-Pritchard, where an ox is cut in half, starting from the neck and all the way to the tail, which is also carefully split in two. Finally, the head is split using an axe.

Leinhardt also describes a peace-making ceremony between two clans, where a member of the first clan had killed a member of the second clan.

He explains that in addition to cattle as a form of restitution, the two clans face each other on either side of a dried-out watercourse.

The master of the spear recites incantations, and then the two clans grab the front and back legs of a sacrificial bull, flipping it on its back.

The master of the spear cuts the animal in half across the stomach symbolizing the severing of the feud and throws part of the entrails of the bull over the participants.

He then plants a spear in the ground and the kinsman come up and bite it, which symbolizes their commitment to the settlement, after which they spit, which represents purification.

The clearly defined sequence and acts performed by the officiant and participants during such rituals, do not bring about a change in the material world, but they bring into being a transformation in the moral universe of the participants, who are now under a clear and widely understood obligation to conform to it.

In conclusion, this essay has illustrated two different approaches to the anthropological study of ritual.

It has shown that Bloch’s studies of the Merina society in Madagascar highlight how religion and ritual are used to maintain power structures and reinforce social hierarchies.

Meanwhile, Lienhardt’s analysis of Dinka rituals emphasizes the transformative impact of ritual on the moral experience of participants and their role in sustaining social cohesion and reinforcing moral values.