The advent of new reproductive technologies has created a tectonic shift in the world of kinship by making available a wide range of options that were previously unthinkable, let alone doable.

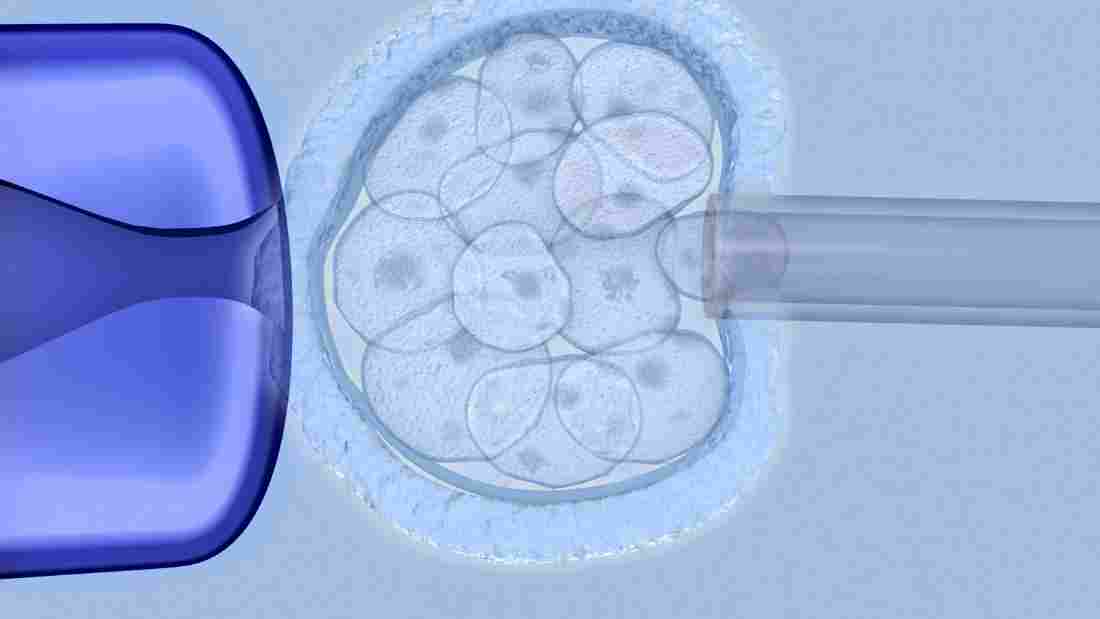

In this essay I will be addressing the implications of donation of gametes in different cultures and also the new types of family formations that have emerged over the last half a century as a result of medically assisted reproduction procedures such as in-vitro fertilization (IVF) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI).

The donation of gametes (eggs or sperm) by third parties to be used during fertility procedures has created a gamut of practical and ethical considerations, a number of which have direct implications for kinship patterns.

These include cases where mothers donate eggs to their daughters, as in the case of Melanie Boivin, who harvested and froze her ova in case her daughter, who was diagnosed with a condition that impacted her ovaries, would want to use them when it came to her having children.

A case like this is presents obvious complications, since the daughter would be giving birth to a child who would be her half-sibling, and her mother would be both the biological mother of the child and the grandparent.

Situations such as these were originally not very common, but they proliferated once IVF became available to gay or lesbian couples, who often used sperm or ova from their siblings in order to conceive a child who is biologically related to them.

Things became even more complex with the advent of surrogacy, since the number of third parties in the conception and gestation of the child grew to include the prospective parent or parents, donors of egg or sperm and the gestational carrier (who in some cases is also a blood relative).

Also interesting is the way that issues such as culture and religion impact preferences regarding the donation of gametes.

Bob Simpson explains the tendency of Sinhalese Buddhists to prefer using sperm from a brother of the husband, linking it to the practice of polyandry that made available culturally-acceptable kinship classifications which allowed for more than one father. He compares this to the strong views of Pakistani Muslims, who categorically reject the use of third-party sperm because they view it as zina (adultery).

The problem regarding zina has created some dramatic behaviours in Muslim societies such as the ones in Lebanon and Egypt (Clarke and Inhorne, in separate studies), where the practice of engaging in endogamous marriages within the kinship group has over time resulted in problems with male fertility. Thus in these countries there is a higher (than the West) percentage of cases where the main causes of infertility in a couple are low sperm counts and sperm motility.

The fatwas issued by both Sunni and Shia Muslim scholars have expressly prohibited sperm donation, which greatly restricted the options available to Muslim couples struggling to beget a child. However, the advent of intracytoplasmic sperm injection technology suddenly changed the options available to them, since the man’s sperm is directly injected into the ovum, making it possible for him to beget a biological child even if his sperm count is abysmally low and the sperm is very weak.

Inhorn tells us that the result of the advent of this technology created a seismic shift in the marriages of many middle-aged couples who had thus far not conceived because of their husband’s infertility. Suddenly this procedure meant that their sub-fertile husbands could fertilize a child, at a time when their own fertility is on the wane.

Both Clarke and Inhorn tell us that this situation has led to one of two behaviours in Lebanon and Egypt.

The first is the contracting of temporary marriages, where the husband marries a younger woman who donates her ova for fertilization with the sperm, which is then implanted in the womb of his first wife. The temporary marriage negates the implication of adultery. Once the procedure is over, the man divorces the second wife and he and his first wife raise the child as their own.

The second way of dealing with the situation is more problematic. If a man ascribes to the belief that a temporary marriage is not sufficient cover to ensure that zina is occurring, and if there are any concerns that the first wife might not be able to carry the child to term even if donated ova are used, a number of men chose to divorce their middle-aged wives and marry a younger wife, having a child with her.

Returning to the West, many anthropologists have studied the impact of ARTs on kinship patterns. These include ethnographies such as the one conducted in San Francisco, a locality that is well-known for welcoming LGBTQI people. The researcher found that same-sex couples who had formed a family using reproductive technologies often went through much more intentional family formation processes than heterosexual couples. In the case of same-sex parents, the construction of kinship networks did not base itself on ties of blood alone, but also on ties of friendship and love – in essence building a “family of choice,” incorporating the people that they themselves chose to have in their children’s lives.

Of course, ARTs are not only used by couples, but they are also used by single people. Single men can use surrogates to beget a child, which single women use sperm donation. In the latter case a new phenomenon which was previously not biologically possible, is the incidence of women past child-bearing age who use IVF in order to have a child. In these cases the children are often born and raised in families where there are no grandparents (because they would have already passed on) and also no cousins who are of the same age. Once again we see different family formation processes in such a scenario, where the mother builds a “family of choice” that could indeed include her siblings and their offspring as blood relatives, but could also include other single mothers and friends who have children of the same age.

In conclusion, this essay has shown that assisted reproductive technologies have had a profound impact on patterns of kinship and marriage. It has made different biological constellations of parentage possible, and also made it possible for couples or single people who would previously not been able to have children to do so. In the process it has also had consequences on marriage, such as the advent of second marriages to ovum donors, and the divorcing of middle-aged wives by Muslim men seeking to beget a child with a younger woman. And finally, ARTs have also led to the proliferation of “families of choice,” where kinship is not based on blood alone, but also on ties of friendship and love.