In this essay, I draw on Sidney Mintz’s seminal book, Sweetness and Power, to examine how the process of commoditisation of sugar both perpetuated and exacerbated relations of inequality on both the production and consumption sides of the equation.

In addition to Mintz’s analysis of sugar, this essay will also explore other examples of food consumption patterns that are reflective of power and domination.

By examining various case studies and historical contexts, this essay aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the complex dynamics between consumption, inequality, and power structures in society.

The History of Sugar

When sugar first arrived in Europe, it was prohibitively expensive, and a ‘marker of rank’ (Mintz 1986: 94). It was a luxury item reserved for the indulgence of kings and the aristocracy, who employed skilled chefs who created intricate sugar sculptures which were called ‘subtleties,’ which were then broken and eaten (Mintz 1986: 89).

The ostentatious sugar displays were not only a signifier of status and wealth, but also a means of delivering political messages, since ‘sly rebukes to heretics and politicians were conveyed in these sugared emblems’ (Mintz 1986: 89).

One could compare the sugar-centred feasts of European elites to the potlatches of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast. The potlatches of the Skagit, for example, were extravagant feasts where guests gorged on highly prized foods such as salmon, symbolizing and highlighting the host’s prosperity and power (Snyder 1975: 156). The display of largesse and excess was brought into sharp relief through the ritualised wastage or destruction of food and other precious items such as canoes.

Thus, both in the case of the European nobility, and that of the potlatchers of the Pacific Northwestern Coast, the ability to provide lavish meals signified wealth, influence, and standing within their respective societies.

Furthermore, the conspicuous consumption inherent in the destruction of the sugar sculptures and the wastage of sucrose during decadent banquets (Mintz 1986; 154) echoes the ritualized wastage and destruction of valuable goods in a potlatch, while the political significance of the subtleties can be compared to the political manoeuvring of potlatchers hosting lavish feasts in a quest to bankrupt their rival in a battle for social status (Mintz 1986; Snyder 1975).

An Expanding Empire

As sugar production within the British empire increased and prices dropped, the use of sugar as a status symbol trickled down the social hierarchy, until it eventually became the domain of the middle classes, with merchants and scholars hosting elaborate feasts ‘comparable to the nobility of the land’ (Mintz 1986: 90).

Over the span of two centuries sugar transformed from a high-cost luxury item accessible only to the very rich (1650) to a low-cost product that was accessible to the poor working classes, who relied on its quick energy boost to fuel their labour-intensive lives (Martinez 2009: 197; Mintz 1986).

As the use of sugar in Britain became ubiquitous, its production became a priority throughout the British Empire, and with it the exploitation of the colonies to meet demand for commodities such as sugar or molasses back home, boosting the fortunes of the British elites and fuelling the back-breaking labour of the working classes.

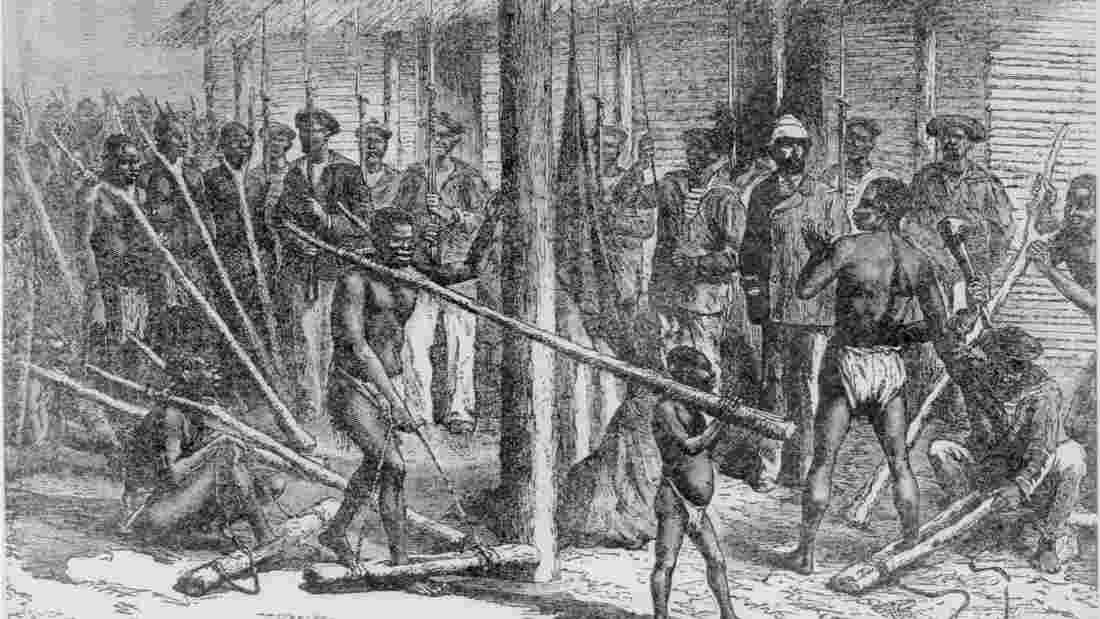

Inexorably, the shift towards volume acted as a catalyst for the seizing of millions of acres of land in the Americas to be developed as sugar plantations, and the importation of millions of enslaved Africans to work on them (Mintz 1986: 157).

In addition to the slaves, plantations also coerced indigenous people to labour in the fields. These workers became entrapped through debt peonage, and they were subjected to the same harsh and abusive working conditions as the slaves (Mintz 1986: 32).

Thus, the commoditisation of sugar is inextricably linked to extreme relations of inequality, both in the centres of production, through the forcible expropriation of land and the extreme exploitation of labour, and in the European centres of consumption, where it became a major driver of profit for the elite, both through the importation and sale of sugar and also by the labour of the working classes who became dependent on it for their nutrition (Mintz 1986: 95).

The New Role of Sugar

At this point, sugar no longer retained its symbolic power as an indicator of status, but a new set of social distinctions came into being, based on the quality of sugar one could afford.

In fact, despite the increased accessibility of the commodity, the consumption patterns of the lower classes differed greatly to those of the rich. The wealthy continued to favour the highly processed white version of sugar, which was more expensive due to its labour-intensive refinement process, while the poor primarily consumed cheap brown sugar or treacle (Mintz 1986: 122). These different forms of sugar not only varied in price but also in their applications and culinary uses.

The elite continued to indulge by presenting guests with sugar sculptures, and treating them to sugar-coated nuts and candied fruit, served on jewel-encrusted plates or drageoirs, broadcasting the host’s wealth and elevated social standing (Mintz 1986: 124).

Some of the elaborate creations that came into being during this era became associated with special events, such as weddings, and in the process were imbued with ceremonial meaning, some of which endures to this day.

The traditional wedding cake is a prime example, with its multiple tiers covered in white icing and embellished with intricate sugar decorations (Mintz 1986: 152), as are the sugar almonds which are often handed out to wedding guests as a token of the bride and groom’s appreciation.

The working class, on the other hand, incorporated sugar into their daily diets in more prosaic ways. According to Mintz, the ‘first sweetened cup of hot tea to be drunk by an English worker was a significant historical event, because it prefigured the transformation of an entire society, a total remaking of its economic and social basis’ (p. 214).

The widespread adoption of sugar is in fact directly linked with industrialisation and the advent of women engaging in paid labour, which required a transition from home-cooked meals to nutritionally inferior but highly calorific meals that could be rapidly prepared after a hard day’s work (p. 139), consisting of sweetened tea and low-quality bread smeared with inexpensive jams or treacle to make it more palatable (Mintz 1986: 127).

A Rigid Social Hierarchy

British society in this era was rigidly hierarchical, and power inequalities in all areas, including food consumption, were inherent in the system.

In fact, Mintz tells us that sugar and food consumption did not only vary between the classes, but that unequal power relations within each class also impacted consumption. In working-class families, for example, men, as the ‘breadwinners’ and heads of the household, ate a disproportionate share of the food available to the family, to the extent that women and children were often chronically malnourished (Mintz 1986 :130).

This did not only happen in the poorest of homes, but also in families that could afford to buy meat, where men ate foods such as bacon almost every day, while the rest of the family only ate it once a week (Mintz 1986 :130).

One should note that this phenomenon is not exclusive to British working-class families in the nineteenth century. Carrier and Heyman (1997) cite an ethnography conducted by Weismantel (1988) of the Zumbagua, in the Ecuadorian Andes.

The young men of the village seek work in the cities, while their wives and children, who are left behind, subsist on produce such as barley and onions cultivated by the women. The men, who earn wages, control the funds, deciding on how much to spend on drinks or entertainment, and how much (if any) to spend on food supplies to augment their families’ diets.

Unequal power relations in the family thus have a direct impact on the nutrition and the development of children, with the ethnographer telling us that the extended kinship group often had to intervene to make recalcitrant husbands and fathers contribute to their family’s nutritional needs (Carrier, Heyman 1997).

The Association of Sugar with the Lower Classes

As time passed the consumption of sugar became associated with the lower classes, who were labelled as ‘lazy’ or ‘lacking self-control’ when it came to consuming products that were high in sugar content and thus viewed as ‘unhealthy’ by the slim, health-conscious upper classes (Bordo 1993), essentially taking the story of sugar consumption as reflective of social inequalities full circle to a complete reversal of its starting position.

Conclusion

In this essay, we have explored the historical dynamics of sugar consumption and production, and how they are both closely tied to various forms of inequality.

The transformation of sugar from an exclusive luxury to a commodity available to the masses highlights the disparities in consumption patterns between the rich and the poor within a society, and how they reflected existing social hierarchies.

Furthermore, the commoditisation of products such as sugar is often linked to new forms of inequalities in the production process, as seen in the exploitative practices of colonisers and the labour conditions associated with sugar cultivation.

The darker aspects of sugar’s history serve as a stark reminder that the quest for profit and expansion can often come at a significant human cost, contributing to the perpetuation of systemic injustices and reinforcing unequal power dynamics.

References

Bordo, Susan (1993) Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body. University of California Press: Berkeley.

Carrier, J., Heyman, J. (1997) “Consumption and Political Economy.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 3(2): 353-373.

Mintz, S. W. (1986) Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History. Penguin.

Snyder, S. (1975) “Quest for the Sacred in Northern Puget Sound: An Interpretation of Potlatch.” Ethnology 14.2 (1975): 149-61. Web.

Martinez, S. (2009) “Towards an Anthropology of Excess,” in Baca, G., Kahn, A., Palmié, S. (eds.), 2009 Empirical Futures Anthropologists and Historians Engage the Work of Sidney W. Mintz. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina