In the colonial era, the African continent generated great wealth for the colonisers, who extracted and spirited away the mineral wealth of the region, while re-investing little to nothing at all in the locality. In the latter half of the twentieth century, Africa was freed from the exploitative yoke of colonialism and a series of structural adjustment programmes were launched, spearheaded by transnational development organisations that promoted a vision of African modernity modelled on that of the West (Ferguson 1999, p. 247; Lucht 2012, pp. 208- 209).

This ethnocentric approach was doomed to failure, and nowadays vast areas of the African continent are still caught in a cycle of abject poverty, with the chronic underdevelopment of the region acting as an impediment to the attraction of new capital and resulting in the total disconnection of these countries from the increasingly connected globalized world, while condemning the people living in the region to an existence that combines abject poverty with little hope of improvement.

The Impact of Globalisation in Sub-Saharan Africa

This essay analyses the impact of globalisation in sub-Saharan Africa, positing that hidden under the promise of transnational access to capital and investment is nothing but a reconfiguration of the extractive methods predominant during the colonial era, enabled by the unequal power relations between countries in the developed versus those in the developing world (Cornwall et al. 2004).

It will also illustrate how the destruction of hope of a better future has resulted in new strategies of survival for the people living in the region, in most cases focused on migration (Pine 2014), even when the risks associated with such endeavours are extraordinarily high because of the violent borders enacted by developed countries (De Leon 2012; Jones 2019).

This harsh reality will be illustrated with examples from the ethnographic book “Darkness before Daybreak” by Hans Lucht (2012), which follows the journeys of migrants from Ghana to Europe, and supported by references to another two ethnographies – one of a Pentecostal congregation in Ghana and the other of South Americans attempting to enter the United States.

The Guan of Senya Beraku

Hans Lucht describes the plight of the Guan, a community of fishermen living in a small fishing village called Senya Beraku, in Ghana, chronicling the economic decline experienced by this community during the period 2002 to 2006, when he conducted his research.

Fish are the mainstay of this community. Their entire economy and even their nutrition is based on the fishermen’s catch, a fact that is poignantly evident by the fact that they do not have a specific word for meat as opposed to fish – ‘in the Guan language the same word, inu, is used for fish and meat, and if one desires a special kind of meat apart from fish, one has to specify, adding the kind of animal one is requesting – for instance, kyidinu, “fowl meat”; owotunu, “bush meat”; or nentwinu, “beef”’ (Lucht 2012, p. 180).

By 2006 the Guan had been brought to their knees because of the massive decline in fish catches. To try to eke out a living, the fisherman had to resort to illegal fishing techniques and in some cases, families had to make the heart-breaking decision to send their children to work in other fishing towns for a fee, where they were employed in slave-like conditions. Girls were made to tend smoke ovens, while young boys worked long hours on the lake without adequate protection, which led to several fatalities. These children do not receive an education and are usually malnourished (Lucht 2012, p. 206).

Fishing Agreements with the EU

The decrease in fish is linked to chronic overfishing, which has been exacerbated by, amongst others, European fishing trawlers illegally entering the West African Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) and using destructive fishing techniques which are forbidden in European Union (EU) waters to catch as many fish as possible.

In addition to these illegal activities, the EU has signed multiple fishing agreements with Western African nations, including Ghana, which allow extensive fishing in the waters of these developing countries, with little to no investment in the infrastructure of the countries in question and with no commitments to generate employment for the natives (Lucht 2012, p. 192).

In essence, the unequal power relations between the EU and the developing countries in Western Africa has enabled them to negotiate fishing agreements and trade deals that have created the same exploitative conditions as were present in the colonial era, with the Europeans siphoning off resources without creating any local jobs or knowledge transfer that could ameliorate the living conditions and wellbeing of African people, whose livelihoods are being destroyed in the process (Lucht, 2012; Cornwall et al. 2004, p. 1431).

The result is total abjection, where the locals experience the very opposite of development, plagued with rampant unemployment and the degradation of essential services such as health and education provision (Lucht 2012, p. 206). This sets off a vicious cycle, where the chronic underdevelopment of the past impedes development in the present, due to the redlining of Africa by the neoliberal world order, which means that global investment flows bypass these nations, (Ferguson 1999, p. 260) in the process accelerating their inevitable slide into destitution (Lucht 2012; Pine 2014).

It is therefore not surprising that the Guan of Senya Beraku view themselves as totally disconnected from the world economy. As one of the fishermen commented in an interview – “We’re not even on the world map. Rather, Senya Beraku is in a cave underground” (Lucht 2012, p. 206).

Migration as a Survival Strategy

Families in Senya Beraku are therefore increasingly coming to view migration as the only strategy that offers hope for a better future, with one or more members of each household being selected to undergo the journey to secure a better future not only for themselves but also for those who are left behind (Pine 2014, p. S98).

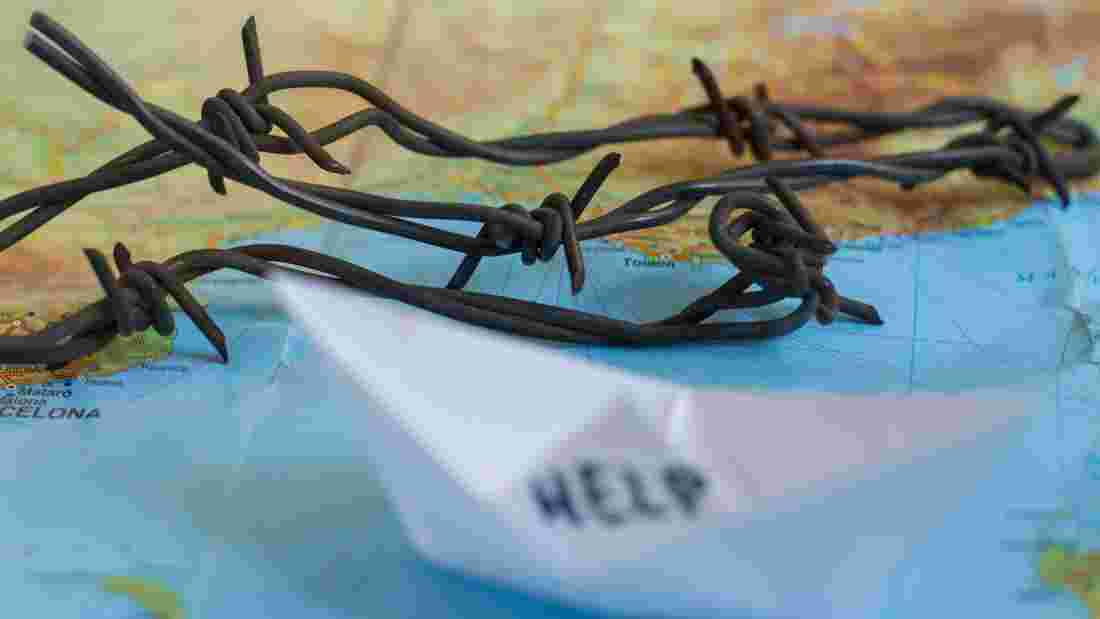

This is not to say that the Guan are not aware of the danger of the journey. While global borders are wide open for the highly educated (Horevitz 2009, p. 749), it is close to impossible for uneducated and low-skilled Africans to enter the European Union through legitimate channels (Lucht 2012).

As a result, migrants are forced to undertake dangerous journeys through the Saharan desert and then across the Mediterranean Sea, which has led to a rise in people smugglers who take advantage of these migrants, and to bandits, who prey on them when they are most vulnerable.

In an interview with Lucht (2012, p. 216), John talks about his brother, Simon, who lost his life at sea when attempting to make the crossing to Europe from Libya. He had set forth on the journey in the hope of making enough money for the family to buy a fishing net and improve their quality of life – “The pain is so deep … it’s still a big blow to us. We know what we had planned and put up against the future . . . to make things easier for us over here. It was supposed to be a turning point in our lives, but unfortunately, he couldn’t make it.”

Notwithstanding the large number of people who lose their life during the journey, the total lack of prospects in Ghana has resulted in most local young men deciding to undertake the journey “even though they are aware of the dangers awaiting them, perhaps having attended the funeral of a friend or relative who did not make it” (Lucht, 2012, p. 180).

The reason for this is that they witness how families with members working in Europe can buy a plot of land and build a home, thus clawing their way out of the desperate poverty that afflicts the community. When questioned about the dangers of the voyage, they accept the risks, often commenting that they prefer death to staying in Ghana and losing all hope of a better future (Lucht 2012).

Migrants Trying to Cross into the US

This all-or-nothing sentiment is echoed by migrants in other countries who face similar economic and social circumstances, and who make the momentous decision to set off on a similar journey.

A good example is that of migrants from South America attempting to enter the United States (De Leon 2012), whose borders are secured by thousands of heavily armed guards, extensive fencing, and advanced detection technologies such as motion sensors and drones. This has forced would-be migrants to attempt the crossing through dangerous regions such as the Sonoran Desert, a journey which has claimed thousands of lives (Rubio-Goldsmith cited in De Leon 2012).

De Leon (2012) finds that migrants are very much aware of the violence and danger they will encounter along the way. As he travels on the bus with two men who are about to attempt to cross the desert for the umpteenth time, one of the two men tells him – ‘A lot of things are going through my head right now. I’m thinking about my family and I’m scared that I am going to die out there. Each time is different; you never know what is going to happen. … The bajadores [armed border bandits] should be out partying tonight because it’s Saturday. We should be able to avoid them. We have food and water and God willing we will get across’ (De Leon 2012, p. 478).

Migration as a Building Block of Identity

Anthropologists conducting fieldwork in Africa and Latin America in the second half of the twentieth century found that declining prospects and increased poverty has led locals to incorporate migration as an essential element in the construction of identity of these communities (Horevitz 2009, p. 747).

Van Dijk (2002) studied a congregation of worshippers at a Pentecostal residential prayer camp in Ghana, the same country studied by Lucht (2012), where the entire doctrine revolved around ‘travel problems’ experienced by those who wanted to emigrate to the West. He tells us that ‘… prophetess Grace Mensah provides for prayer sessions over passports, visa and air-tickets, and urges those who come for ‘travel-problems’ to engage in dry-fasting as it is called; that is, no food and water for the maximum number of days a human body is able to sustain such a regime.’ (van Dijk 2002, p. 53)

What is interesting is that the Ghanaian Pentecostal churches serve a dual role. In Ghana they help to deconstruct and change the old ethnic identities and communal values of its members, legitimising and sacralising their desire to leave their kinship group and venture out into the world to improve their lot in life. However, they then follow the migration flows and set up branches in locations where many Ghanaians settle in the West, at which point the main aim changes from deconstruction and change to reconstruction and maintenance.

Crossing the Mediterranean Sea – A Rite of Passage

The transformation in identity of the Ghanaian migrants is also mentioned by Lucht, who describes the Mediterranean crossing as the liminal phase of a rite of passage during which the migrants change identity – “the journey is a strategy not only for moving physically and geographically but also for moving ahead in life, socially and existentially” (Lucht 2012, p. 136).

When they finally make it to Italy, the migrants reconstruct their identity as “burgers and tycoons, as people with power and connections, when confronted with the harsh realities and nullification of illegal immigrant life” (Lucht 2012, p. 159).

Conclusion

Those who make it across the treacherous waters of the Mediterranean Sea, arriving in countries such as Italy, have finally closed the cycle that started in the West, first through colonisation and then through the ramifications of globalisation.

The flow of migrants follows the flow of natural resources, including marine resources, that is taken from Sub-Saharan Africa and appropriated by Western countries, who then complain about the influx of economic migrants arriving through irregular means across the border.

The only way to stop these migrants making the journey is not to make the border crossings more dangerous and violent, which has already been attempted with tragic results, but to stop the exploitative trade and fishing agreements that are decimating the economies of communities in the developing world and killing any hope that these people may have of being able to earn a decent living in their country of origin.

Bibliography

Cornwall, A., Nyamu-Musembi, C. (2004) ‘Putting the “Rights-Based Approach” to Development into Perspective.” Third World Quarterly, 25(8), pp. 1415-1437.

De Leon, J. (2012) ‘“Better to Be Hot than Caught”: Excavating the Conflicting Roles of Migrant Material Culture.’ American Anthropologist, 114(3), pp. 477-495.

Ferguson, J. (1999) Expectations of Modernity: Myths and Meanings of Urban Life on the Zambian Copperbelt. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Horevitz, E. (2009) ‘Understanding the Anthropology of Immigration and Migration’ Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 19(6), pp. 745-758.

Jones, R. (2019) ‘From Violent Borders: Refugees and the Right to Move. NACLA report on the Americas.’ 51(1), pp. 36-40.

Lucht, H. (2012) Darkness before Daybreak. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press.

Pine, F. (2014) ‘Migration as Hope: Space, Time, and Imagining the Future.’ Current Anthropology, 55, pp. S95-S104.

Van Dijk, R. (2002) ‘The soul is the stranger: Ghanaian Pentecostalism and the Diasporic contestation of “flow” and “individuality.”’ Culture and Religion, 3(1), pp. 49-65.

Disclosure: Please note that some of the links in this post are affiliate links. When you use one of my affiliate links, the company compensates me. At no additional cost to you, I’ll earn a commission, which helps me run this blog and keep my in-depth content free of charge for all my readers.