In 1997, representatives of working children from Asian, African and Latin American countries participated in three international conferences organised by the International Labour Organization (ILO), a United Nations (UN) agency focused on protecting the rights of workers worldwide. In their contributions the children emphasized that they had the right to work ‘with dignity and appropriate hours,’ which would leave them time for education and leisure (White 1999, p. 140).

Their intervention highlights the tension created between the social and economic realities of the regions in which they live and the application of human rights conventions such as article 32 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) (1989), which affirms ‘the right of the child to be protected from economic exploitation and from performing any work that is likely to be hazardous or to interfere with the child’s education…’ (White 1999, p. 133).

It also casts a spotlight on the fact that the policymakers who drafted the CRC, and the international development organisations who were entrusted with its implementation, had not consulted any children regarding its contents, a glaring omission when one considers that article 12 (1) of the CRC states that any ‘child who is capable of forming his or her own views [has] the right to express those views freely, on all matters affecting the child, the views of the child being given due consideration in accordance with the age and maturity of the child’ (Pupavac 2001, p. 99).

The setting of global standards and human rights by organisations such as the UN, the ILO, or the World Education Forum (WEF), with its Education for All (EFA) action framework, sought to establish not only universal human rights but also universal norms and practices, without giving much leeway for flexibility relating to local cultural and economic realities (Stromquist 2001; White 1999; Nishimuko 2009).

In essence, these conventions took on the form of international decrees dictating what is in the best interest of the child, and how that best interest is to be attained, based on a Western understanding of what it means to be a child and an assumption that children develop in the same way globally (Pupavac, 2001).

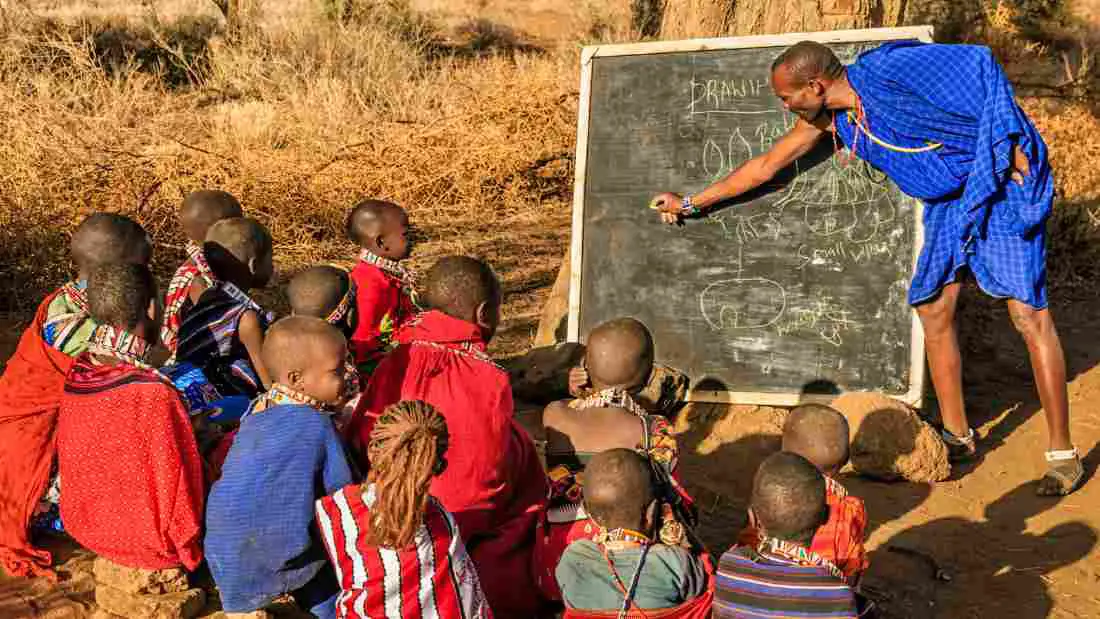

Consequently, organisations such as UNESCO, which has been entrusted with the international implementation of the EFA, have based their interventions in developing countries on Western models of school-based education, in most cases ignoring the social realities on the ground (Pupavac 2001).

The UN Development Programme (UNDP) has earmarked education as a crucial catalyst of long-term development, pointing to studies by the World Bank that found that disparities in educational attainment were linked to variances in economic growth between nations with comparable natural resource bases and investment levels (Browne et al. 1991).

Furthermore, educating women has been highlighted as a priority, since maternal education has been linked to reduced fertility, higher child survival rates, and improved hygiene, health, and nutrition for the entire family (Browne et al. 1991; Stromquist 2001; Silver et al. 2022).

In this essay I will be focusing on school-based educational programmes implemented by international development organisations in developing countries, and the issues encountered during their implementation, using examples from Malawi (Silver et al. 2022), Ghana (Lucht 2012) and other countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (Browne et al. 1991); India (Boo 2012); and Latin America (Stromquist 2001).

I will also discuss the approach taken by an international development agency in Sierra Leone (Nishimuko 2009), which successfully navigated the pitfalls which plagued educational interventions in other countries, enabling us to learn important lessons that can be extended to other regions.

One of the most crucial problems encountered by international development organisations when they embark on classroom-based education programmes is the fact that many children in developing countries need to work to help sustain the family (Browne et al. 1991; White 1999; Pupavac 2001; Stromquist 2001; Lucht 2012; Boo 2012). There is a tendency, when talking about human rights, including children’s right to an education, to divorce the discussion from social and economic conditions, based on the assumption that education will in and of itself empower the poor to emancipate themselves and claw their way out of poverty (White 1999; Stromquist 2001; Pupavac 2001).

This conveniently glosses over the international power-inequalities and asymmetric trade deals that place developing countries at a serious disadvantage in today’s globalised world, and which are ultimately responsible for the lack of opportunities and blighted economies that make it practically impossible for the poor in these countries to improve their living conditions, thus creating the necessity for children to work in the first place (White 1999; Cornwall et al. 2004; Lucht 2012).

One must also question the assumption that the poor are poor because they are not educated and ask whether the reverse is true. Is it education that leads to poverty, or is it poverty that restricts access to education? (Stromquist 2001).

In the case of Ghana, for example, the European Union negotiated a fishing agreement that enables European trawlers to decimate marine life in the region, leading to entire fishing villages falling into total destitution. As a result, school budgets were slashed and many children had to be taken out of school and sent to work in other fishing communities in slave-like conditions (Lucht 2012, pp. 203, 206).

Similar situations exist throughout sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America, where schools often do not have budgets to acquire teaching materials and books (Browne et al. 1991, p. 282), and many families cannot afford to buy school supplies such as pencils and copybooks, let alone other essentials such as uniforms or shoes (Havelin 1999 as cited in Stromquist 2001, p. 42)

In Ecuador, on the other hand, families find themselves ‘having to sell chickens to buy notebooks’ if they are to keep children in school (CEIMME 1995 as cited in Stromquist 2001, p. 43).

Another serious impediment to school-based education in developing countries is the lack of physical infrastructure and adequately trained educators. A study conducted in Peru found that 90% of schools in rural areas consisted of a single classroom, and 37% only had one teacher, who is usually underqualified, inexperienced, and not trained to manage multigrade classrooms. Furthermore, many of the schools did not have electricity, running water, or adequate toilet facilities (Stromquist 2001, p. 42).

Similarly, in rural areas of Malawi, it is not uncommon for schools to have teacher to student ratios of 1:200 in multigrade classrooms (Silver et al. 2022, p. 440). The same applies to India, where pupils attending free municipal schools often sit in class with no teacher, or else find themselves being “taught” by people who only have a primary school education themselves (Boo 2012).

The situation relating to the education of girls encounters several additional roadblocks. Attending a school with no toilet facilities is particularly problematic for women. The situation is exacerbated in cases where female students do not have access to sanitary pads. In fact, the impact of menstruation on absenteeism is so high that scholarships in Malawi provide a stock of sanitary pads along with a uniform and school supplies (Silver et al. 2022, p. 438).

Cultural views and stereotypes regarding the role of women in society also hampers girls’ access to school. In Boo’s ‘Behind the Beautiful Forevers’ (2012), for example, we learn about Meena, an Indian low-caste Dalit whose parents believed that “Too much learning reduced a girl’s compliancy” (Boo 2012, p. 76). Other ethnographies uncover several similar gendered stereotypes, showing that expectations regarding family and housework obligations result in girls either not being sent to school in the first place, or being taken out of school earlier than boys (Browne et al. 1991; Stromquist 2001).

These gendered norms can also hamper educational interventions run by international NGOs. A perfect example are the programmes run by the United States Agency for International (USAID) and the UK Department for International Development’s (DFID) in Malawi, whose goal is a reduction in girls’ school dropout rate by providing access to sexual education in schools.

This information was to be provided by teachers and mothers trained by the agencies, but the projects failed because of the ingrained cultural norms that led to teachers and mothers, despite the training provided, naming and shaming girls who were sexually active and punishing them when they were found in the possession of contraceptives, in essence doing exactly the opposite of what the NGO had set out to do (Silver et al. 2022).

In addition to all the above, many educational intervention programmes run by international development agencies fail because they do not take into consideration local power imbalances, which results in funds being misappropriated or redirected towards projects that benefit people other than those who need it most.

In India, for example, government officials and members of the elite recruited a network of frontmen running non-profit organisations purportedly committed to educating poor children, and secured funds from the Indian government and foreign donors as part of the EFA initiatives, but they never actually spent any of it on the intended beneficiaries (Boo 2012, p. 214).

Similar problems were encountered in Latin America, where the elites misappropriated funds that were intended for schools in poverty-stricken areas (Stromquist 2001).

It is evident that the formulaic approach taken by international development agencies, which does not take into consideration local social and economic circumstances, including the impact of pre-existing unequal power relations, has doomed many school-based educational interventions to failure. This does not mean, however, that it is not possible to achieve success in this area.

An excellent case study that illustrates how such educational interventions can be sensitively designed according to local needs, attaining positive results for all concerned, is the case of Sierra Leone, one of the poorest countries in the world, whose economy and infrastructure had been decimated by a bloody civil war that lasted from 1991 to 2002 (Nishimuko 2009).

Several international development agencies are currently working in Sierra Leone, with the largest in the educational field being Plan Sierra Leone (PSL). When the projects started, the education infrastructure in Sierra Leone was very poor, and in rural areas there were schools where teachers were poorly qualified, and which had high student to teacher ratios. However, progress is now being made, with PSL investing in projects that include building and renovating primary schools, supplying school furniture, training teachers through workshops and distance learning, and distributing school supplies like pens, pencils, teaching and learning materials to help run schools effectively (Nishimuko 2009).

This practical approach ensures that the physical infrastructure is improving, while also giving due focus to improving the human resources, enabling educators to improve the quality of their teaching, and ensuring that schools have the wherewithal to run efficiently and effectively – achievements that should not be taken for granted given the failure of similar projects for exactly these reasons in other countries.

The main differentiating factor in PSL’s approach is that instead of rolling out the implementation of its initiatives itself, as happened in the examples above relating to USAID and DFID, it partnered with local NGOs who are deeply rooted in the communities they serve, and who bring local knowledge into the equation, ensuring that the educational interventions they deliver are fit for the desired purpose. Thus, PSL’s role is to (1) make available the funds required for the project, (2) help the local NGOs build the required capacity to manage and run the project, and (3) monitor usage of the funds to ensure that the monies are benefiting those for whom it was intended (Nishimuko 2009).

It is also very important to note that the investment made in education is not happening in isolation, but rather as part of a slew of other initiatives coordinated by an overarching Poverty Reduction Strategy adopted in 2005 by the government of Sierra Leone, in recognition of the fact that education alone is not enough to pull people out of poverty. On the education front the strategy includes the provision of financial assistance to families for the purchase of books, uniforms, and other school essentials, along with legislation empowering the authorities to fine or even imprison guardians who do not send their children to school (Nishimuko 2009, p. 285).

Ethnographic research has identified several issues of a practical nature that impede the provision of school-based-education in developing countries. These include (1) the economic reality that some children must work in order to help support the family, (2) a lack of school infrastructure, (3) untrained, underpaid and inexperienced educators, working under difficult conditions with very high student to teacher ratios, (4) cultural norms that restrict female emancipation, (5) the inability of families to afford school supplies and, and (6) manoeuvres by the elites to misappropriate education funding for the poor.

Unfortunately, these issues have contributed to the failure of several education interventions in developing countries. It is therefore crucial, if progress is to be made, that international development organisations rethink their approach, taking a step back to assess case studies such as the one of Sierra Leone, to learn from previous mistakes and emulate strategies that have proven to be successful.

References

Boo, K. (2012) Behind the Beautiful Forevers: Life, Death, and Hope in a Mumbai Undercity. Random House, Inc., New York.

Browne, A.W., Barrett, H.R. (1991) £Female Education in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Key to Development?” Comparative Education, 27 (3), pp. 275-285.

Cornwall, A., Nyamu-Musembi, C. (2004) “Putting the ‘Rights-Based Approach’ to Development into Perspective.” Third World Quarterly, 25 (8), pp. 1415-1437.

Llewellyn-Fowler, M., Overton, J. (2010) “’Bread and Butter’ Human Rights: NGOs in Fiji.” Development in Practice, 20 (7), pp. 827-839.

Lucht, H. (2012) Darkness before Daybreak. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press.

Nishimuko, M. (2009) “The Role of Non-Governmental Organisations and Faith-Based Organisations in Achieving Education for All: The case of Sierra Leone.” Compare, 39 (2), pp. 281-295.

Pupavac, V. (2001) “Misanthropy Without Borders: The International Children’s Rights Regime.” Disasters, 25 (2), pp. 95-112.

Silver, R., Morley, A. (2022) “Girls’ Education and Sexual Regulation in Malawi. Gender and Education,” 34 (4), pp. 429-445.

Stromquist, N.P. (2001) “What Poverty Does to Girls’ Education: The Intersection of Class, Gender and Policy in Latin America.” Compare, 31 (1), pp. 39-56.

White, B. (1999) “Defining the Intolerable: Child Work, Global Standards and Cultural Relativism.” Childhood (Copenhagen, Denmark), 6 (1), pp. 133-144.

Disclosure: Please note that some of the links in this post are affiliate links. When you use one of my affiliate links, the company compensates me. At no additional cost to you, I’ll earn a commission, which helps me run this blog and keep my in-depth content free of charge for all my readers.